10

Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(4):1868-1905. doi:10.7150/ijbs.120624 This issue Cite

Review

Post-translational modifications in ferroptosis: mechanisms and therapeutic potential

School of Ocean and Tropical Medicine. Guangdong Medical University, Zhanjiang, Guangdong, 524023, China.

#Equal contribution.

Received 2025-6-30; Accepted 2025-10-20; Published 2026-1-22

Abstract

Ferroptosis has been demonstrated to play pivotal roles in a spectrum of pathological processes, including multi-organ dysfunction, retinal degeneration, neurodegenerative disorders, autoimmune diseases, and tumorigenesis. Notably, its pivotal role in counteracting cancer drug resistance positions ferroptosis as a promising therapeutic target. The precise regulation of this cell death pathway is fundamentally dependent on the functional orchestration of associated proteins, where subtle modifications can exert profound effects on ferroptotic progression. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) serve as sophisticated molecular switches that dynamically regulate protein structure, activity, subcellular localization, and functional interactions through covalent attachment of biochemical groups or regulatory subunits. These modifications - including proteolytic processing, partial degradation, or complete protein turnover - significantly expand the functional repertoire of the proteome, thereby exerting crucial regulatory control over cellular survival decisions. This comprehensive review systematically examines the intricate crosstalk between ferroptosis and major PTM pathways, with particular emphasis on ubiquitination, phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation, methylation, oxidative modifications, glycosylation, S-nitrosylation, lactylation, and lipidation. Through critical analysis of current research advances, we elucidate the mechanistic basis by which PTMs modulate ferroptotic pathways and discuss their therapeutic implications. Furthermore, we provide prospective insights into emerging research directions and potential clinical applications targeting PTM-mediated ferroptosis regulation.

Keywords: ferroptosis, post-translational modifications, molecular regulation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination

Introduction

Ferroptosis is a form of non-apoptotic cell death characterized by iron-dependent Lipid peroxidation (LPO) of cellular membranes[1]. The onset of ferroptosis is primarily attributed to the effects of ferroptosis-promoting factors or prerequisites outweighing the cellular antioxidant mechanisms and defensive systems against ferroptosis. From a mechanistic standpoint, factors that induce ferroptosis can exert direct or indirect effects on the phospholipid hydroperoxidase, glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), via multiple pathways. This results in a diminished intracellular antioxidant capacity and an accumulation of lipid-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS), subsequently leading to membrane disruption and culminating in cellular demise[2]. Recent studies have indeed demonstrated that ferroptosis is closely associated with the pathophysiological processes of numerous diseases, including autoimmune diseases, neurological disorders, ischemia-reperfusion injury, renal damage, hematological diseases, and particularly in the context of cancer and its resistance to chemotherapy, which holds significant potential[3]. Ferroptosis underlies pollutant-elicited organ injury; its pharmacological modulation (Nrf2 activators, iron chelators) constitutes an emerging therapeutic axis against environmental health hazards[4]. Numerous pathways can modulate ferroptosis, including metabolic pathways and degradation pathways, which can play a double-edged sword role in disease therapy. Similarly, an increasing number of studies have found that ferroptosis can also be regulated in the process of epigenetics, including histone PTMs, DNA methylation, non-coding RNA regulation, and PTMs[5]. Epigenetic alterations have garnered considerable attention due to their significance in regulating biological processes and their potential as therapeutic targets. Among these, PTMs drive the dynamic dysregulation of transcription or translation, and more importantly, key PTMs modulating ferroptosis have been identified as potential targets for cancer therapy. The functional involvement of two protein subunits, solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and GPX4, in ferroptosis resistance has been extensively studied in recent years. Studies have indicated that PTMs play a positive role in the treatment of diseases by modifying ferroptosis-related proteins in liver cancer[6].

PTMs represent a chemical modification that targets the structural diversity and functional specificity of the proteome[7]. PTMs regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally, thereby modulating protein activity, structure, and function[8]. Research indicates that the dynamic interplay between protein degradation pathways and PTMs offers potential therapeutic targets to modulate the onset of ferroptosis[9]. The extensive repertoire of PTMs is instrumental in modulating the mechanisms of ferroptosis within cellular and organelle contexts[10]. Ubiquitination of specific lysine residues on proteins associated with ferroptosis can hinder the resistance to ferroptosis conferred by Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1 (FSP1)[11]. Deubiquitinating enzymes contribute to the recycling of ubiquitin by degrading ubiquitin polymers, thus playing a pivotal role in the regulation of ferroptotic mechanisms. A dynamic regulatory mechanism modulating ferroptosis involves the complex interplay between SUMOylation and ubiquitination, which can influence cellular ferroptosis by either upregulating or downregulating ubiquitination[9]. Phosphorylation, a widely occurring covalent modification among PTMs, exerts a substantial influence on the modulation of ferroptotic processes through its covalent modifications on proteins such as GPX4[12], within the Hippo signaling pathway[13][14], the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway[15], and in ferroptosis metabolism[16]. The dynamic regulation by protein kinases and protein phosphatases further establishes phosphorylation as a crucial regulatory mechanism in ferroptosis. Lipidation directs proteins to cellular organelles and the plasma membrane, augmenting their membrane affinity. This includes four non-exclusive types of lipidation: glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchoring, N-myristoylation[17], S-palmitoylation[18], and S-prenylation, which can occur singularly or in combination on the same protein and are potentially linked to ferroptosis. Acetylation, encompassing proteins such as tumor protein p53 (TP53), ALOX12, HMGB1, HSPA5, and histones, is implicated in the modulation of ferroptosis, either by promoting or inhibiting the process[9]. Methylation, another PTM that targets both histone and non-histone proteins, is integral to cellular function and has been found to have a connection with ferroptosis[9]. High oxidation peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3) has been identified as a potential biomarker for ferroptosis in chronic liver disease[19]. Oxidative modifications which can lead to alterations in protein function, have garnered our interest. Glycosylation, one of the major PTMs, has not been extensively studied in its association with ferroptosis, but research has found that glycosylation of the heavy chain subunit of system Xc- can induce the susceptibility of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to ferroptosis[20]. S-nitrosylation is a reversible PTM that serves to stabilize proteins, regulate gene expression, and provide a nitric oxide (NO) donor in cells. Ferroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can be achieved by reducing intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels via NO donors, elevating malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, inhibiting the expression of SLC7A11/GSH proteins, and negatively regulating the JAK2/STAT3 pathway[21]. Lysine lactylation, derived from lactic acid, is a novel PTM that provides insights into the function of lactic acid and its role in infection and inflammation, and here we discuss its connection with ferroptosis[22].

PTMs, each with their unique characteristics, are not entirely independent of each other. Proteins can be subject to not only a single modification but also to two or more modifications simultaneously. Therefore, there exists an interconnected and complex network system of potential PTMs. In summary, there is a close relationship between ferroptosis and the PTMs network system. Consequently, studying PTMs in the context of ferroptosis holds promising prospects for the development of drugs with high specificity, selectivity, and low toxicity for the treatment of various diseases and cancers in the future.

1. The Process of Ferroptosis and its Regulatory Mechanisms

1.1. The Antioxidant Basis of Ferroptosis

Cells possess an integrated array of antioxidant defense mechanisms that rigorously prevent excessive accumulation of lipid peroxides and the ensuing initiation of ferroptosis. Recent years have seen the discovery of four GPX4-independent systems that effectively inhibit ferroptosis. FSP1/coenzyme Q10, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1)/tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), and MBOAT1/2-MUFA each independently inhibit ferroptosis apart from GPX4. Below, we will provide a brief overview of these common antioxidant pathways against ferroptosis.

1.1.1. SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4

GPX4 is the most important protein against ferroptosis; it is a selenocysteine-containing protein, and selenium can enhance the cell's antioxidant capacity during ferroptosis. Consequently, GPX4 utilizes GSH as a cofactor to convert lipid peroxides into non-toxic metabolites, thus preventing the buildup of lipid peroxides. The antioxidant GSH is a tripeptide composed of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine. Due to the limited concentration of cysteine in cells, cysteine is considered the rate-limiting precursor for GSH synthesis. Cystine, in its oxidized state, is transported into the cell via the system Xc- and promptly reduced to cysteine intracellularly. System Xc- is a heterodimeric protein complex composed of the regulatory subunit solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2) and the catalytic SLC7A11. This complex facilitates the exchange of extracellular cystine and intracellular glutamate on the plasma membrane. Cystine in the cell is reduced to cysteine, which is essential for the production of GSH. GPX4 uses GSH to eliminate the formation of phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOH), thus inhibiting ferroptosis[23, 24].

GPX4 constitutes the linchpin of the antioxidant machinery that counteracts ferroptosis; abundant evidence now indicates that pharmacological modulation of GPX4 exerts a Janus-faced influence on ferroptosis-dependent therapeutic outcomes across a spectrum of diseases. PTMs enhance the functional versatility of the proteome through the addition of functional groups or covalently attaching regulatory subunits to proteins, proteolytic cleavage of proteins, or the degradation of entire proteins. GPX4 inactivation, stemming from mutations or covalent modifications of the active site selenocysteine, impairs its function in halting the complex lipid oxidation cascade, thus augmenting ferroptosis[25]. For tumor, DMOCPTL, a derivative of parthenolide (PTL), has been identified as a potential therapeutic agent targeting triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells. It induces ferroptosis by ubiquitinating GPX4[26]. Creatine kinase B (CKB) can induce ferroptosis by ubiquitinating GPX4. Specifically, CKB phosphorylates GPX4 at the Ser104 residue, thereby preventing its degradation and counteracting ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, ultimately promoting tumor growth[12]. In Alzheimer's disease, SIRT1 depletion attenuates GPX4 deacetylation, suppressing its peroxidase activity, thereby potentiating lipid peroxidation and exacerbating amyloid-β-triggered neurotoxicity. During myocardial ischemia-reperfusion(I/R), AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of GPX4 at Ser104 inactivates the enzyme, precipitating cardiomyocyte ferroptosis[27]. In non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the Tibetan remedy Huagan Tongluo Formula (HGTLF) triggers ferroptosis of hepatic stellate cells via ubiquitin-dependent degradation of GPX4, consequently ameliorating hepatic fibrosis[28]. These findings offer novel perspectives on the modulation of ferroptosis via the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis. Nevertheless, additional studies are required to investigate whether different PTMs can modify the proteins in this pathway.

1.1.2. NADPH-FSP1-CoQ10

FSP1 has been identified as a second ferroptosis-inhibitory system when combined with extracellular ubiquinone or exogenous vitamins K and NAD(P)H/H+ as electron donors, all of which exhibit significant radical trapping antioxidant (RTA) activity and can effectively prevent LPO. FSP1 is localized on the plasma membrane, where it can produce CoQ10 (also known as ubiquinone), an endogenous electron carrier, and the reduced form of vitamin K. FSP1, an NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase, catalyzes the reduction of CoQ10 to its reduced form, CoQ10-H2, thereby scavenging LPO radicals and inhibiting LPO and the initiation of ferroptosis[29]. Apart from CoQ10, FSP1 is also capable of regenerating reduced vitamin K, an additional endogenous RTA that can restrict LPO and ferroptosis[30]. Several investigations have demonstrated that the inhibition of the FSP1-CoQ axis can effectively reverse radioresistance[31]. Research has found that modifications to FSP1 through PTMs can also affect ferroptosis. Since the N-terminus of FSP1 contains a typical myristoylation motif, and myristoylation is a lipid modification that promotes the binding of target proteins to the cell membrane, the myristoylation of the N-terminus of the FSP1 protein facilitates the localization of FSP1 to the plasma membrane, which is crucial for its ferroptosis-inhibiting activity[17, 32, 33]. Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 1 (ACSL1) can reduce the level of lipid oxidation and increase the resistance to ferroptosis in cells. Mechanistically, ACSL1 increases the N-myristoylation of FSP1, thereby inhibiting its degradation and translocation to the cell membrane. The increase in myristoylated FSP1 functionally counteracts cell ferroptosis induced by oxidative stress[34]. Sorafenib triggers ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by facilitating TRIM54-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of FSP1[35]. RNF126 interacts with FSP1 and ubiquitinates FSP1 at the 4KR-2 site, acting as an anti-ferroptotic gene. Furthermore, the lack of RNF126 diminishes the subcellular localization of FSP1 at the plasma membrane, resulting in an elevated CoQ/CoQH2 ratio in G3-medulloblastoma[36]. Exogenous nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) Interacts with N-myristoyltransferase 2, leading to the upregulation of N-myristoylated FSP1. This interaction facilitates the membrane localization of FSP1 and augments its resistance to ferroptosis[37]. The perspective of resisting ferroptosis through N-myristoylation and ubiquitination of FSP1 provides a promising avenue for the regulation of ferroptosis mechanisms; however, we still require a substantial amount of research to expand and validate its therapeutic efficacy in actual clinical settings for diseases.

1.1.3. GCH1-BH4

GCH1-BH4 is a novel pathway for regulating ferroptosis identified through metabolic-focused CRISPR-Cas9 gene screening and genome-wide dCas9-based activation screening (CRISPRa). Overexpression of GCH1 not only eliminates LPO but also nearly completely blocks the occurrence of ferroptosis. Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), a constituent of the antioxidant system, is implicated in the metabolism of NO, neurotransmitters, and aromatic amino acids. GCH1 serves as the rate-limiting enzyme in BH4 synthesis[38]. By synthesizing BH4 via GCH1 and subsequently reducing dihydrobiopterin (BH2) to BH4 through dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), BH4 functions as an endogenous anti-ferroptotic RTA[39]. Additionally, studies have shown that cells with overexpressed GCH1 have phospholipids protected by two polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) chains, thereby enriching the reduced CoQ10 levels post-ferroptosis induction, such as under IKE treatment[40]. The GCH1-BH4 pathway, as an endogenous antioxidant pathway, inhibits ferroptosis through mechanisms independent of the GPX4/GSH system. Current ferroptosis research on the GCH1-BH4 axis remains confined to “abundance/activity” metrics (transcriptional control, protein level fluctuations, BH4 synthesis rate), leaving its post-translational landscape virtually unexplored. Systematic mapping of GCH1 phosphorylation, ubiquitination, or acetylation, together with oxidative/nitrosative modifications of BH4, represents an urgent and tractable knowledge gap.

1.1.4. DHODH-CoQH2

DHODH operates in parallel with mitochondrial GPX4 (but independently of cytosolic GPX4 or FSP1), and is located on the outer surface of the mitochondrial inner membrane (IMM), where it intercepts LPO radicals by reducing CoQ10 to CoQH2, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis within the IMM[41]. In overcoming cancer's resistance to chemotherapy, research indicates that the depletion of proline-rich protein 11 (PRR11) markedly enhances the sensitivity of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells to temozolomide (TMZ) through the induction of ferroptosis. Mechanistically, PRR11 directly interacts with and stabilizes DHODH, conferring resistance to glioma ferroptosis in a DHODH-dependent manner both in vivo and in vitro. Moreover, PRR11 inhibits the recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin ligase HERC4 and prevents the polyubiquitination and degradation of DHODH at the K306 site, thereby maintaining DHODH protein stability. Notably, the downregulation of PRR11 augments LPO and disrupts DHODH-regulated mitochondrial morphology, consequently facilitating ferroptosis and increasing TMZ chemosensitivity in GBM cells[42]. Lysyl oxidase-like 3 (LOXL3) depletion significantly sensitizes liver cancer cells to oxaliplatin (OXA) by inducing ferroptosis. Chemotherapy-activated EGFR signaling drives the interaction between LOXL3 and TOM20, leading to the hijacking of LOXL3 to mitochondria, where the lysyl oxidase activity of LOXL3 is enhanced through phosphorylation at the S704 site. Metabolic adenylate kinase 2 (AK2) directly phosphorylates LOXL3-S704. Phosphorylated LOXL3-S704 targets DHODH and stabilizes it by preventing its ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation. K344-deubiquitinated DHODH accumulates in mitochondria, thereby inhibiting chemotherapy-induced mitochondrial ferroptosis. In a late-stage liver cancer mouse model, the combination of low-dose OXA with the DHODH inhibitor leflunomide effectively inhibits liver cancer progression by inducing ferroptosis, increasing chemotherapy sensitivity, and reducing chemotherapy toxicity[43]. This all demonstrates the potential of the DHODH-CoQH2 pathway, and targeting this pathway may be able to regulate the resistance of cancer cells to ferroptosis inducers.

1.1.5. MBOAT1/2-MUFA

Increasing evidence suggests that steroid hormones are central regulators of several ferroptosis regulatory systems. The expression of membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain containing 1 and 2 (MBOAT1/2), driven by sex hormones, can enable cancer cells to escape ferroptosis. MBOAT1 and MBOAT2 are transcriptionally upregulated by the sex hormone receptors estrogen receptor (ER) and androgen receptor (AR), respectively. The combination of ER or AR antagonists with ferroptosis inducers can significantly inhibit the growth of ER+ breast cancer and AR+ prostate cancer, even when the tumors are resistant to monotherapy with hormone treatment alone[44]. Phospholipids laden with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are prone to LPO. Conversely, MBOAT2 preferentially integrates monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) into phospholipids, indicating that MBOAT2 might mitigate ferroptosis by competitively lowering the PUFA levels in phospholipids. In fact, lipidomics analysis has shown that overexpression of MBOAT2 specifically increases phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) containing MUFAs while decreasing PUFA-PE, thereby enhancing resistance to ferroptosis[45, 46]. Although no PTMs of MBOAT1/2 have yet been reported, the pivotal MUFA-synthesizing enzyme SCD1 and its upstream lipoylation machinery are known to be PTM-regulated. This suggests that manipulation of PTMs in these peripheral enzymes may offer an indirect yet potent strategy to modulate the ferroptosis-suppressive function of the MBOAT1/2-MUFA axis.

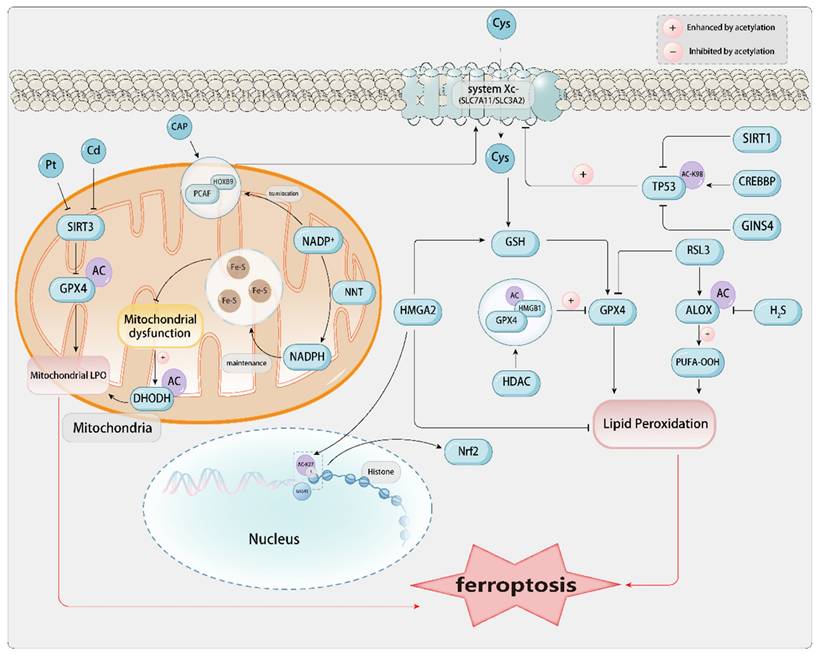

1.2. The Core Mechanism of Ferroptosis and Related Metabolism[Figure 1]

ROS are produced by chemical reactions between lipids, oxygen, and iron. Phospholipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA-PLs; fatty acids with multiple double bonds) are the main substrates in the process of ferroptosis. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) activates free polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly arachidonic acid (AA) and adrenic acid (AdA), into PUFA-CoA. Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) then incorporates these acyl-CoAs into phosphatidylcholine/ethanolamine, generating PUFA-PLs that are enriched in the cell membrane and mitochondrial membrane, serving as a reservoir for lipid peroxidation (Dai et al., 2024). Subsequently, lipoxygenases from the linoleate/arachidonate lipoxygenase family (ALOX) catalyze the formation of lipid hydroperoxides (PLOOH) from PUFA-PLs, thereby promoting ferroptosis. Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) is also a redox enzyme that, independent of ALOX, can promote the peroxidation of polyunsaturated phospholipids. It transfers electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen, forming H2O2, which induces cells to undergo Fenton reactions with Fe2+, promoting the peroxidation of PUFAs, thereby inducing ferroptosis[47]. However, the development of ferroptosis associated with PUFAs can be effectively blocked by the production and stimulation of MUFAs. This blockage is facilitated by acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3 (ACSL3) or stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD/SCD1)[48]. Conversely, attenuation of IR/SREBP axis-mediated MUFA synthesis facilitates ferroptosis in HCC[49].

If the aforementioned processes are considered as the establishment of a “fuel depot” for ferroptosis, then iron acts as an “igniter” in this context. The role of iron in ferroptosis is “trifunctional”: i) It serves as a catalyst for the Fenton reaction, directly generating the hydroxyl radicals required for lipid peroxidation; ii) It acts as a cofactor for iron-containing enzymes such as ALOXs and cytochrome P450, continuously producing lipid peroxides; iii) It provides a continuous supply of free iron through ferritinophagy, thereby forming a positive feedback loop that amplifies the death signal. Extracellular Fe3+ in the body binds to ferroportin (FPN) on the cell membrane, forms a complex with the membrane protein TF receptor 1 (TFRC), and is transported into the cell through endocytosis[50]. Upon cellular uptake, Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ by the six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 3 (STEAP3) within the endosome, subsequently being translocated into the cytoplasm via the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) protein[51]. Fe2+ in the cytoplasm and mitochondria establishes a labile iron pool (LIP), and through the mediation of Fenton reaction-induced LPO, it shows oxidative activity and induces ferroptosis. The iron-catalyzed non-enzymatic Fenton chain reaction could be pivotal to ferroptosis. Upon inhibition of GPX4, PLOOHs may endure for extended durations, and the onset of the Fenton reaction can swiftly escalate the levels of PLOOHs. PLOOHs can react with Fe2+, producing radical PLO• and PLO•, respectively. These radicals react with PUFA-PLs, further propagating the production of PLOOHs and promoting the occurrence of ferroptosis. Furthermore, research has discovered that the process of ferritin autophagy mediated by nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) can degrade ferritin, releasing the iron stored within it into the LIP, enhancing the availability of iron within cells, and thereby promoting LPO-driven ferroptosis[52, 53]. Moreover, hepcidin binds to FPN1 on the cell membrane surface, thereby promoting the endocytosis and degradation of FPN1. This process inhibits iron absorption by intestinal epithelial cells and iron recycling from aged erythrocytes by macrophages.

The core mechanisms of ferroptosis and related antioxidant pathways. a. Iron metabolism Fe3+ binds to TF and enters the cell via endocytosis through TFR, subsequently associating with lysosomes. Fe3+ dissociates from TF and is reduced to Fe2+ by STEAP3, then transported to the cytoplasm by DMT1, where it accumulates to form the LIP. Fe2+ from the LIP can be similarly stored in FT and transported to the mitochondria to support oxidative respiration, and it can also form autophagic lysosomes mediated by NCOA4. Fe2+ catalyzes the non-enzymatic Fenton reaction of PUFA-PLs, leading to the accumulation of lethal lipid peroxides, which triggers ferroptosis. It also acts as an essential cofactor for POR and ALOX to promote the progression of ferroptosis. Fe2+ can be exported to the extracellular space via FPN. b. Lipid metabolism PUFAs are catalyzed by ACSL4 and LPCAT3 to form PUFA-PLs, which are further oxidized by ALOX to produce PUFA-OOH, ultimately leading to the formation of LPO that induce ferroptosis. c. Amino acid metabolism The system Xc- (composed of SLC7A11 and SLC3A2) transports Cys and Glu into the cell. Glutamine enters the cell via SLC1A5 and is converted to Glu. Glu provides Cys for GSH synthesis through GCL. GPX4 utilizes GSH to reduce PL-PUFA-OOH to harmless products, preventing lipid peroxidation of the cell membrane. Similarly, the cell also has related antioxidant pathways, including the GPX4/xCT pathway, FSP1/CoQH2 pathway, DHODH/CoQH2 pathway, and GCH1/BH4 pathway, which can detoxify lipid peroxides and thus protect cells from ferroptosis damage.

The core mechanism of ferroptosis is implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of many diseases. For instance, the immediate surge of free Fe²⁺ during reperfusion drives lipid peroxidation mediated by ACSL4/Alox15, and the peroxidation of mitochondrial cardiolipin leads to the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), resulting in ferroptosis of cardiomyocytes. Blocking iron uptake or lipid oxidation by using TFR1 antibodies, Alox15 inhibitors, or GPX4 activators within 5-30 min can reduce infarction by 40%[54].

Amino acid metabolic processes constitute a significant determinant in the induction of ferroptosis. When discussing SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4, we mentioned that cysteine (Cys), an important synthetic rate-limiting precursor of GSH, is a crucial cofactor for GPX4. During the progression of aortic aneurysms, downregulation of GPX4 and SLC7A11, coupled with the accumulation of LPO, leads to ferroptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and endothelial cells. This process triggers medial degeneration and the formation of dissections[55]. The exogenous sources of Cys are through the direct absorption of Cys by excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3) and alanine/serine/cysteine/threonine transporter 1, or through the intake of cystine via SLC7A11 and SLC3A2, which is then converted to Cys in the cytoplasm through the catalyzation of glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL). The endogenous source of Cys involves the transsulfuration pathway, which includes the conversion of methionine to S-adenosylmethionine by the rate-limiting enzyme methionine adenosyltransferase 2A (MAT2A), followed by a series of biochemical reactions, ultimately forming Cys[56]. However, the level of Cys within cells can also be suppressed. Cysteine dioxygenase (CDO1) facilitates the transformation of Cys into taurine. In this process, CDO1 competes with GCL for Cys, effectively redirecting Cys that would otherwise be utilized for the synthesis of GSH towards taurine biosynthesis[57]. The suppression or functional inactivation of CDO1 facilitates the repletion of intracellular GSH levels, mitigating the accumulation of reactive ROS and LPO. This, in turn, enhances cellular resilience against ferroptosis and fosters tumor growth[58, 59]. As another precursor for GSH synthesis, glutamate can aid in the formation of GSH and NADPH. Extracellular glutamine (Gln) enters the cell via SLC1A5 (ASCT2) and is converted to glutamate (Glu) under the catalysis of glutaminase (GLS), which is used with Cys and Gly to produce GSH. The synthesized GSH and NADPH serve to sustain redox homeostasis[60, 61].

Lipid metabolism, iron metabolism, and amino acid metabolism complement and influence each other in the process of ferroptosis, interweaving into the metabolic network of ferroptosis. Among these, PTMs of ferroptosis related proteins hold significant potential for regulating cellular ferroptosis. For instance, protein kinase C beta II (PKCβII) promotes the generation of PUFA-PLs by phosphorylating ACSL4. This process in turn increases the phosphorylation of NCOA4, leading to enhanced ferritinophagy and the release of more free iron. Consequently, the lipid peroxidation cascade is amplified[16]. AMPK phosphorylates BECN1, which leads to an increased formation of the BECN1-SLC7A11 complex. This results in reduced cystine uptake, impaired synthesis of GSH, and inactivation of GPX4, thereby further inducing ferroptosis[62]. In the treatment of liver cancer, Erastin can trigger de-O-GlcNAcylation of TFRC at serine 687 (Ser687), thereby reducing the binding of the ubiquitin E3 ligase membrane-associated RING-CH8 (MARCH8) and decreasing polyubiquitination on lysine 665 (Lys665), which enhances the stability of TFRC that favors the accumulation of labile iron and promotes the occurrence of ferroptosis[63]. The anti-proliferative effects of small molecule ferroptosis modulators, particularly class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, is markedly reliant on the ferroptosis pathway. The HDAC inhibitor HL-5s demonstrates significant antagonistic efficacy toward class I HDACs, with a particular focus on HDAC1. Mechanistically, HL-5s increases YB-1 acetylation, inhibits the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) signaling pathway, elevates Fe2+ levels, and generates ROS through the Fenton reaction, ultimately promoting the production of LPO, which triggers ferroptosis[64]. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway, which is related to inflammatory signaling, promotes the expression of hepcidin by activating STAT3, thereby inhibiting iron efflux[65]. In zebrafish exposed to high iron levels, IL-22 triggers STAT3 phosphorylation, leading to increased hepcidin expression and hepatic iron accumulation. This results in iron overload-induced ferroptosis in the liver[66]. Some scholars have also confirmed in animal experiments that ferroptosis can be precisely “switched on and off” within minutes through reversible PTMs such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, or deacetylation. In a mouse model, AAV9-SIRT3 mediated deacetylation of GPX4 reduced the infarct size in I/R injury by 25%. In patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, the USP14 inhibitor IU1, when used in combination with cisplatin, increased ubiquitination of GPX4, thereby inducing ferroptosis in more tumor cells and reducing tumor volume. These studies have achieved quantifiable therapeutic effects at the mouse/rat level and may provide new targets for drug development[67]. We will provide a more detailed discussion on different PTMs in the subsequent sections.

2. The Regulatory Role of PTMs in Ferroptosis

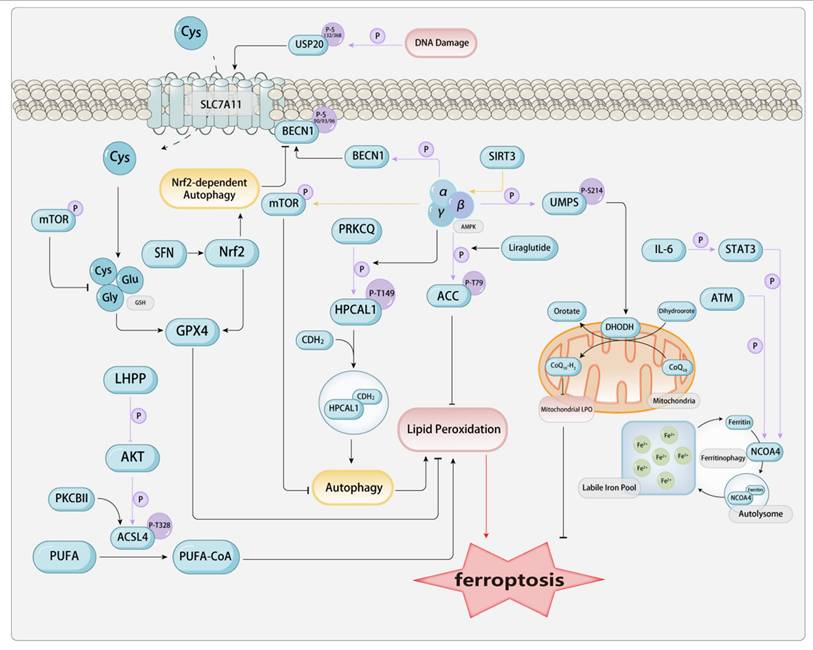

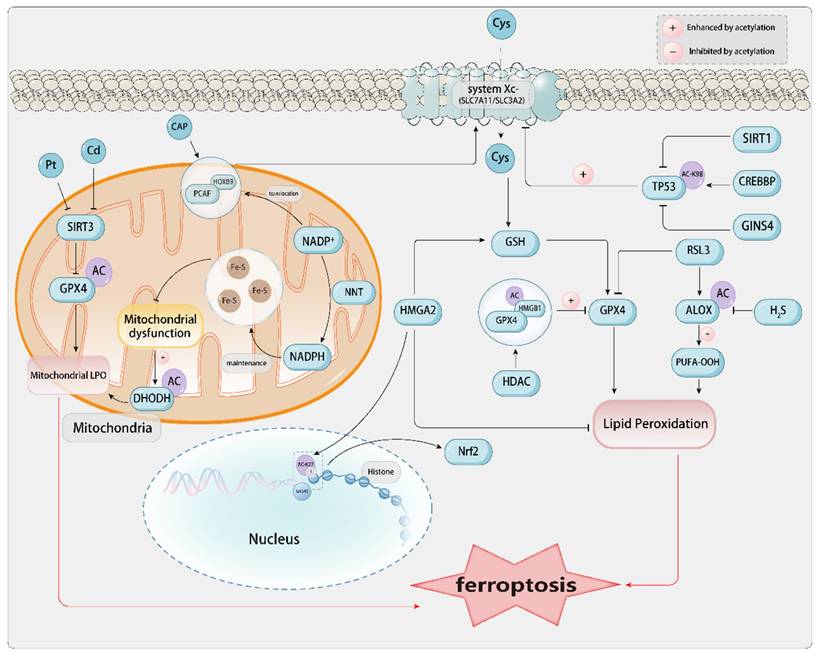

PTMs refer to the collective term for specific chemical modifications at the protein level. After amino acids within the cell are transcribed into mRNA and translated into inactive proteins, these proteins are endowed with activity and functionality through covalent modifications and linkages with different functional groups or proteins[68], regulatory hydrolytic cleavage of protein subunits, or partial or complete degradation. This process leads to differentiation at various structural levels of proteins, diversification in function, and enrichment of the proteome within the cell. The occurrence of PTMs is of significant importance for the normal operation of cell proliferation, death, localization, and function[9]. PTMs can occur at any stage of the protein life cycle, and they are typically mediated by specific enzymatic activities. Therefore, depending on the nature of different PTMs, these processes are reversible and function to modulate ferroptosis, thereby affecting the sensitivity of diverse pathophysiological mechanisms[9]. The dysregulation of PTMs may lead to abnormal expression of protein characteristics, even transformation into malignant phenotypes, further inducing the occurrence and progression of diseases[68]. The interaction between PTMs and protein degradation mechanisms[69] also provides multiple approaches and pathways for the intervention of ferroptosis.[Error! Not a valid bookmark self-reference.]

The mechanisms of various protein modifications in the context of disease-related ferroptosis. Provides a comprehensive summary of the PTMs exerted by various enzymes on ferroptosis-related proteins, elucidating their mechanisms and potential associations with ferroptosis-related diseases.

| Modification | Targets | Site | Enzyme | Disease | Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination | GSTP1 | K121/191/55 | SMURF2 | Cancer | SMURF2 primarily promotes the degradation of GSTP1 protein by catalyzing the polyubiquitination of GSTP1 at K121/191/55 sites, thereby promoting ferroptosis. | [73] |

| Ubiquitination | FSP1 | K322/366 | TRIM21 | - | TRIM21 can promote the K63-linked ubiquitination of FSP1 at K322 and K366 sites, disrupting the plasma membrane localization and the resistance of FSP1 to ferroptosis | [9] |

| Ubiquitination | NCOA4 | - | TRIM7 | GBM | Overexpression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM7 leads to the ubiquitination of NCOA4, inhibiting NCOA4-mediated ferroptosis in GBM. | [71, 72] |

| Ubiquitination | GPX4 | K48 | TRIM25 | Pancreatic cancer | TRIM25 is activated by E2 Ubc5 domain, enabling N6F11 to activate the UbcH5b-TRIM25-GPX4 ubiquitination cascade, triggering ferroptosis in cancer cells. | [76] |

| Ubiquitination | SLC7A11/xCT | K37 | TRIM3 | NSCLC | Overexpression of TRIM3 can increase ROS levels and lipid peroxidation in cancer cells, promoting ferroptosis. | [77] |

| Ubiquitination | VDAC2/3 | - | Nedd4 | Melanoma | The E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 degrades the voltage-dependent anion channel VDAC2/3 by binding to the PPxY motif of VDAC2/3 through its WW domain. | [78] |

| Ubiquitination | GPX4 | - | Nedd4 | PD | Nedd4 mediates the ubiquitination of GPX4, disrupting its function and inducing ferroptosis. | [79] |

| Ubiquitination | TfR1 | - | HUWE1 | I/R | TfR1 for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, regulating iron metabolism, counteracting abnormal iron accumulation, inhibiting ferroptosis, and potentially mitigating acute liver injury caused by I/R. | [80] |

| Ubiquitination | hnRNPA1 | - | USP7 | GC | USP7 stabilizes hnRNPA1 through deubiquitination, mediating the entry of miR-522 from cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment into exosomes. | [82] |

| Ubiquitination | SCD | - | USP7 | GC | The USP7 inhibitor DHPO induces ferroptosis in gastric cancer, and the inhibition of USP7 by DHPO increases the ubiquitination of SCD, accelerating its proteasomal degradation, thereby inhibiting the growth and metastasis of GC. | [83] |

| Ubiquitination | GPX4 | K48 | USP8 | Colorectal tumor | USP8 stabilizes GPX4 by removing K48-linked ubiquitination on GPX4, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and potentially enhancing cancer immunotherapy. | [84] |

| Ubiquitination | histone 2A | - | BAP1 | Cancer | The tumor suppressor BAP1 reduces the occupancy of H2Aub at the SLC7A11 promoter. | [85] |

| Ubiquitination | SLC7A11 | K48 | SOCS2 | HCC | SOCS2 promotes ferroptosis by facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of SLC7A11, where SLC7A11 polyubiquitination mainly occurs in the form of K48-linked ubiquitin chains. | [86] |

| Ubiquitination | Sirt3 | - | USP11 | Gallbladder cancer | USP11 can directly bind to Sirt3 and deubiquitinate Sirt3 to stabilize Sirt3, inhibiting its degradation. The occurrence of IVDD downregulates the level of Sirt3, upregulates the level of oxidative stress, induces ferroptosis, and exacerbates patient pain. | [93] |

| SUMOylation | Nrf2 | K110 | SENPs | HCC | Enhance Nrf2's activity in scavenging ROS, ultimately enhancing the tolerance of liver cancer cells to oxidative stress. | [95] |

| SUMOylation | ACSL4 | - | SENP1 | Lung cancer | Overexpression of SENP1 inhibits ferroptosis induced by Erastin or cisplatin, reduces the expression of ACSL4, and induces the expression of SLC7A11. | [68] |

| SUMOylation | FSP1 | K162 | SENP3 | - | SENP3 interacts with and de-SUMOylation FSP1 at the K162 site, sensitizing macrophages to ferroptosis. | [101] |

| SUMOylation | TRIM28/ACSL4 | K532 | SENP3 | Spinal cord injury | The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM28 is upregulated in spinal cord injury, catalyzing the conjugation of SUMO3 to lysine 532 of ACSL4. | [104] |

| Phosphorylation | ACC | T79 | AMPK | - | AMPK mediates the phosphorylation of ACC, inactivating it by phosphorylating the threonine at position 79, which promotes fatty acid oxidation, reduces serum free fatty acids, and subsequently decreases lipid deposition in tissues, improving lipid metabolism. | [103] |

| Phosphorylation | BECN1 | S90/93/96 | AMPK | CRC | AMPK-induced phosphorylation of BECN1 can promote the formation of the BECN1-SLC7A11 complex and LPO. | [62] |

| Phosphorylation | AMPK-mTOR | - | SIRT3 | Gestational diabetes | The activation of SIRT3 depletes the activation of the AMPK-mTOR pathway and enhances GPX4 levels, thereby inhibiting autophagy and ferroptosis. | [107] |

| Phosphorylation | UMPS | S214 | AMPK | Cervical cancer | AMPK phosphorylates the S214 site of UMPS and enhances pyrimidine body assembly, thereby promoting DHODH-mediated resistance to ferroptosis. | [110] |

| Phosphorylation | ACSL4 | - | PKCβII | - | PKCβII, by sensing initial lipid peroxides, amplifies ferroptosis-related LPO through the phosphorylation and activation of ACSL4. | [16] |

| Phosphorylation | ACSL4 | T624 | LHPP | Prostate cancer | LHPP interacts with AKT, thereby inhibiting AKT phosphorylation, which subsequently inhibits the phosphorylation of ACSL4 at the T624 site. | [117] |

| Phosphorylation | GPX4 | S104 | IGF1R-AKT-CKB | HCC | IGF1R signal activates AKT to phosphorylate CKB at the T133 site, reducing its metabolic activity and increasing its binding and phosphorylation with GPX4 at the S104 site. | [12] |

| Acetylation | TP53 | K98R+3KR | CREBBP | Acute lung injury | CREBBP as a key acetyltransferase for TP53 acetylation, suppresses the expression of SLC7A11 at the transcriptional level in an acute lung injury model. | [9, 126] |

| Acetylation | p53 | - | SIRT1 | kidney stones | The activation of the deacetylase SIRT1 or the triple mutation of p53 induces the deacetylation of p53, inhibits ferroptosis, and alleviates renal fibrosis caused by CaOx crystals. | [129] |

| Acetylation | ALOX12 | - | CSE/H2S | - | CSE/H2S can attenuate the acetylation of ALOX12 and prevented lipid peroxidation in the membrane. | [135] |

| Acetylation | HMGB1 | - | HDAC | - | Various oxidative stresses can induce the release of highly acetylated HMGB1 under various pathological conditions, which can induce the occurrence of ferroptosis. | [136] |

| Acetylation | Mitochondrial GPX4 | - | SIRT3 | AKI | The downregulation of SIRT3 may lead to mitochondrial GPX4 acetylation involved in cadmium-induced renal cell ferroptosis. | [137] |

| Acetylation | FSP1 mRNA | N4 | NAT10 | Colon cancer | The N4 acetylation modification of FSP1 mRNA is associated with the inhibition of ferroptosis, and the knockdown of NAT10 significantly increases ferroptosis in colon cancer cells. | [138] |

| Acetylation | NNT | K1042 | IL-1β | GC | Under IL-1β stimulation, the NNT in cancer cells is acetylated at lysine 1042, inducing the mitochondrial translocation of PCAF, which maintains sufficient iron-sulfur clusters and protects tumor cells from ferroptosis. | [145] |

| Methylation | Histone H3 | K4 | KMT2B | I/R | KMT2B accelerates the RFK by enhancing H3 methylation levels, thereby activating the TNF-α/NOX2 pathway and promoting ferroptosis induced by myocardial I/R. | [149] |

| Lipidation | HpETE-PEs | - | 15LO1-PEBP1 | Asthma | 15-LO1 in HAECs forms a 15-LO1-PEBP1 complex with PEBP1, which generates iron-avid HpETE-PEs that lipidate the autophagy protein microtubule LC-3I, forming membrane-bound lipidated LC3-II. This process stimulates the initiation of protective autophagy, allowing cells to escape ferroptosis and the release of mitochondrial DNA. | [161] |

| N-myristoylation | FSP1 | - | ACSL1 | Ovarian cancer | The upregulation of ACSL1 reduces the levels of LPO, thereby enhancing the cells' resistance to ferroptosis. FSP1 as a potential candidate for N-myristoylation, further augments ferroptosis resistance in an ACSL1-enhanced manner. | [34] |

| N-myristoylation | FSP1 | - | NADPH/NMT2 | Neurodegenerative diseases | Exogenous NADPH interacts with NMT2, upregulating N-myristoylated FSP1. NADPH increases the membrane localization of FSP1, enhancing resistance to ferroptosis. | [37] |

| Palmitoylation | CD8+ T cell | - | CPT1A | Lung cancer | CPT1A identified as a key rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid oxidation, which acts in concert with l-carnitine from tumor-associated macrophages to drive ferroptosis resistance and CD8+ T cell inactivation in lung cancer. | [172] |

| Palmitoylation | SLC7A11 | Cys327 | ZDHHC8 | GBM | SLC7A11 undergoes S-palmitoylation, which is catalyzed by ZDHHC8, a member of the PAT, at the Cys327 site, thereby reducing the ubiquitination level of SLC7A11. | [18] |

| Palmitoylation | IFNγ signaling pathway | - | - | CRC | IFNGRs and Janus kinase/STAT1 can modulate the IFNγ signaling pathway through palmitoylation. The downregulation of the two subunits of system Xc-, SLC3A2 and SLC7A11, impairs the tumor cells' cystine uptake, promoting LPO and ferroptosis in tumor cells. | [174] |

| Palmitoylation | GPX4 | Cys66 | ZDHHC20 | - | The Cys66 residue of GPX4 is palmitoylated by the acyltransferase ZDHHC20, thereby increasing its stability and mitigating ferroptosis. Conversely, inhibition of the depalmitoylase APT2 enhances GPX4 palmitoylation, promoting ferroptosis resistance. | [175] |

| Glycosylation | Ferritin heavy chain | Ser179 | RSL3 | - | RSL3 lead to the removal of O-GlcNAc from serine 179 of the ferritin heavy chain, which increases its binding to the ferritin receptor NCOA4. This modification results in the accumulation of labile iron within the mitochondria. | [185] |

| Glycosylation | SLC3A2 | - | B3GNT3 | PDAC | B3GNT3 can catalyze the glycosylation of SLC3A2, stabilize the SLC3A2 protein, and enhance the interaction between SLC3A2 and xCT. | [20] |

| Glycosylation | SREBP1 | - | ALG3 | Cancer | Inhibition of ALG3 induces defects in post-translational N-linked glycosylation modifications and leads to excessive lipid accumulation in cancer cells through SREBP1-dependent lipogenesis, inducing immunogenic ferroptosis in cancer cells. | [187] |

| Lactylation | PCK2 | Lys100 | KAT8 | IRI | Hyperlactatemia exacerbates ferroptosis in hepatic IRI by activating KAT8, which lactylates PCK2 at Lys100, thereby enhancing its kinase activity. | [207] |

| Histone Lactylation | Histone H3 | K18 | p300 | Sepsis | Lactate regulates the level of m6A modification by promoting the binding of lysine 18 on histone H3 acetylated by lysine acetyltransferase p300 to the METTL3 promoter site. | [208] |

2.1. Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination is the process by which ubiquitin, a polypeptide composed of 76 amino acids, combines with target substrates to form ubiquitin chains. Specific lysine (K) residues are the primary sites for ubiquitination. The sequential cascade of catalytic reactions mediated by E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin ligases orchestrates the entire ubiquitination process[9]. Ubiquitination is considered a tightly regulated PTM, and Deubiquitinases (DUBs) can reverse the process of ubiquitination[70], regulating protein stability and degradation. Ubiquitination has now become a key regulatory mechanism in ferroptosis. For example, Overexpression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM7[71] leads to the ubiquitination of NCOA4, inhibiting NCOA4-mediated ferroptosis in GBM[72].

2.1.1. FSP1-Related Ubiquitination

In the early stages of ferroptosis, the ubiquitination and degradation of glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) mediated by the SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase 2 (SMURF2) lead to a significant downregulation of GSTP1. SMURF2 primarily promotes the degradation of GSTP1 protein by catalyzing the polyubiquitination of GSTP1 at K121/191/55 sites, thereby promoting ferroptosis[73]. Recent investigations have revealed a strong correlation between K63-linked ubiquitination and the plasma membrane localization of target proteins, as well as the role of FSP1 in ferroptosis inhibition. Specifically, the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM21 has been shown to facilitate K63-linked ubiquitination of FSP1 at K322 and K366, which disrupts the plasma membrane localization and ferroptosis resistance of FSP1[9]. In pancreatic cancer, TRIM21 facilitates tumor growth and gemcitabine resistance while inhibiting ferroptosis through the suppression of arachidonic acid metabolism mediated by Microsomal epoxide hydrolase 1 (EPHX1). Bezafibrate can disrupt the interaction between TRIM21 and EPHX1, thereby enhancing the efficacy of gemcitabine and presenting a novel therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer[74]. Edaravone, a new ferroptosis inhibitor, stabilizes FSP1 protein levels by inhibiting FSP1 ubiquitination, suppresses ferroptosis, and alleviates doxorubicin (DOX)-induced cardiotoxicity[75].

2.1.2. SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 Pathway- Related Ubiquitination

The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM25 binds to the ferroptosis inducer N6F11, mediating the K48 polyubiquitination of GPX4. TRIM25 is activated by the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) Ubc5 domain, enabling N6F11 to activate the UbcH5b-TRIM25-GPX4 ubiquitination cascade, triggering ferroptosis in cancer cells[76]. The expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM3 is significantly reduced in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), which are predominant subtypes of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), but overexpression of TRIM3 can increase ROS levels and LPO in cancer cells, promoting ferroptosis[77]. In melanoma cells, the E3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4 degrades the voltage-dependent anion channel VDAC2/3 by binding to the PPxY motif of VDAC2/3 through its WW domain. Conversely, Erastin induces ferroptosis by directly binding to VDAC2/3, thereby altering the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane and decreasing the rate of NADH oxidation[78]. Nedd4 also mediates the ubiquitination of GPX4, disrupting its function and inducing ferroptosis, elucidating the mechanisms underlying dopaminergic neuronal degeneration in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease (PD)[79]. The HECT domain-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase HUWE1, as a negative regulator of ferroptosis, specifically targets the transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, regulating iron metabolism, counteracting abnormal iron accumulation, inhibiting ferroptosis, and potentially mitigating acute liver injury caused by ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)[80]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase RC3H1 stabilizes the GPX4 protein via the cleavage of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation protein 1 (MALT1), thereby exerting an inhibitory effect on ferroptosis. The MALT1 inhibitor MI-2 not only induces ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells but also demonstrates synergistic anticancer effects when combined with sorafenib or regorafenib. The crucial role of MALT1 in the ferroptosis pathway underscores its potential as a novel therapeutic target for cancer treatment[81].

Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) stabilizes heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1) via deubiquitination, facilitating the entry of miR-522 from cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment into exosomes. These exosomes are subsequently activated by cisplatin and paclitaxel, leading to downregulation of ROS levels in gastric cancer cells, inhibition of ferroptosis, and reduced chemotherapy sensitivity[82]. At the same time, studies have found that USP7 promotes tumorigenesis by increasing the levels of stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD). The USP7 inhibitor DHPO induces ferroptosis in gastric cancer, and the inhibition of USP7 by DHPO increases the ubiquitination of SCD, accelerating its proteasomal degradation, thereby inhibiting the growth and metastasis of gastric cancer[83]. Ubiquitin-specific protease 8 (USP8) stabilizes GPX4 by removing K48-linked ubiquitination, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and potentially enhancing cancer immunotherapy[84]. The tumor suppressor BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1) diminishes the occupancy of histone 2A ubiquitination (H2Aub) at the SLC7A11 promoter, thereby downregulating SLC7A11 expression in a deubiquitination-dependent manner. Additionally, BAP1 curtails cystine uptake by repressing SLC7A11 expression, which subsequently escalates LPO and ferroptosis[85]. Highly expressed cytokine signaling 2 inhibitor (SOCS2) promotes ferroptosis by facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of SLC7A11, where SLC7A11 polyubiquitination mainly occurs in the form of K48-linked ubiquitin chains[86]. The tumor suppressor PCDHB14 promotes the ubiquitination of p65, preventing it from binding to the SLC7A11 promoter, downregulating the levels of SLC7A11 in HCC, and enhancing ferroptosis[87].

In cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), the expression of SLC7A11 is upregulated due to the increased expression of shank-associated RH domain interacting protein (SHARPIN), a component of the linear ubiquitin chain complex[88]. The inactivation of SLC7A11 due to ubiquitination also induces ferroptosis in NSCLC[89] and ovarian cancer cells[68]. The downregulation of p21 expression due to p53 ubiquitination subsequently induces ferroptosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) cells by inhibiting GPX4[90]. GPX4 is a well-recognized significant negative regulator of ferroptosis[91], and DMOCPTL, as the first reported to induce ferroptosis by ubiquitinating GPX4 and downregulating GPX4 levels, supports the treatment of TNBC[26]. The potential mechanism of low back pain caused by intervertebral disc degeneration (IVDD) is partly considered to be ferroptosis. Polydopamine nanoparticles (PDA NPs) colocalize with GPX4 around the mitochondria, inhibit ubiquitin-mediated degradation, downregulate the production of MDA and LPO, and antagonize ferroptosis in nucleus pulposus cells[92]. Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) is a key regulator of mitochondrial ROS, and it plays a role in promoting the expression of GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis in gallbladder cancer. Ubiquitin-specific protease 11 (USP11) can directly bind to Sirt3 and deubiquitinate Sirt3 to stabilize Sirt3, inhibiting its degradation. The occurrence of IVDD downregulates the level of Sirt3, upregulates the level of oxidative stress, induces ferroptosis, and exacerbates patient pain[93]. The androgen receptor (AR) enhances the drug resistance of GBM to TMZ, and curcumin analog ALZ003-mediated AR ubiquitination causes astrocytoma cells to undergo ferroptosis, potentially opening up new avenues for the treatment of TMZ-resistant GBM[94].[Table 2]

2.2. SUMOylation

SUMOylation, a PTM characterized by the covalent attachment of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins to target proteins, plays a crucial role in diverse cellular processes and serves as a vital cellular mechanism for stress response. Importantly, SUMOylation is a reversible and dynamic process[68]. It conjugates to the lysine (Lys) residues of substrate proteins during the PTM process. There are five SUMO isoforms in mammalian cells, namely SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO3, SUMO4, and SUMO5. SUMO molecules are covalently attached to target proteins via an enzymatic cascade analogous to the ubiquitin cascade, which entails the sequential involvement of E1, E2, and E3 enzymes. Conversely, SUMO-specific proteases, SENPs (SENP1, SENP2, SENP3, SENP5, SENP6, and SENP7), catalyze de-SUMOylation and precursor processing. The balance of cellular SUMOylation is determined by the restrictive SUMO precursors and mature SUMO isoforms, as well as the SENP family[95].

Based on their distinct subcellular localizations and substrates, SENPs are categorized into three distinct classes: The first category comprises SENP1 and SENP2, which are localized to the nuclear pore or PML nuclear bodies in interphase cells and exhibit broad isopeptidase activity against SUMO1, SUMO2, and SUMO3; The second category encompasses SENP3 and SENP5, which are localized to the nucleolus and have high specificity for SUMO2 and SUMO3; the third category includes SENP6 and SENP7, which are localized to the nucleoplasm and are relatively inclined to cleave SUMO2 and SUMO3 chains. SENP6 and SENP7 have minimal involvement in precursor processing; in contrast, SENP1, SENP2, and SENP5 participate in the SUMO maturation process[95]. Emerging research indicates that SUMOylation regulate ferroptosis in cancer. The upregulation of ROS levels, particularly H2O2, and the occurrence of LPO are typical characteristics of ferroptosis. In various cancers, the overactivation of the SUMO pathway is considered a selective advantage in combating stress. It is hypothesized that this is a mechanism by which cancer cells enhance their tolerance to ROS-induced upregulation to avoid death. The modulation of ferroptosis-related proteins via SUMOylation has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy. Even in extracts of certain traditional Chinese herbal components, such as ginkgolic acid (GA) induces ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells by targeting the SUMOylation marker SUMO1 activating enzyme subunit 1 (SAE1), thereby exerting anti-liver fibrosis effects[96].

2.2.1. SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 Pathway- Related SUMOylation

A series of sites susceptible to ferroptosis are targets of SUMOylation, including the central ferroptosis inhibitor GPX4, which inhibits the peroxidation of membrane phospholipids and participates in ferroptosis after SUMO modification. Nrf2, an antioxidant transcription factor intricately linked to ferroptosis, undergoes ubiquitination at the conserved lysine residue K110. SUMOylation can enhance Nrf2's activity in scavenging ROS, ultimately enhancing the tolerance of liver cancer cells to oxidative stress[95]. Overexpression of SENP1 attenuates ferroptosis triggered by Erastin or cisplatin, downregulates ACSL4 expression, and upregulates SLC7A11 expression. Elevated SENP1 levels are associated with adverse prognoses in lung cancer patients[68]. In cervical cancer (CC) cells, CoCl2-stimulated hypoxia-like conditions specifically enhance the SUMO1 modification of KDM4A at K471, inhibit H3K9me3 levels, upregulate SLC7A11/GPX4, and thereby enhance the resistance of CC cells to ferroptosis[97]. In breast cancer (BC) cells, the protein inhibitor of activated STAT4 (PIAS4) promotes the SUMOylation of SLC7A11 by directly binding to it, while lysine-specific demethylase 1A (KDM1A) acts as its transcriptional activator. Tanshinone IIA reduces the expression of KDM1A, thereby transcriptionally inhibiting the expression of PIAS4. Inhibition of PIAS4-dependent ubiquitination of SLC7A11 further induces ferroptosis, which suppresses the proliferation and metastasis of BC. Therefore, Tanshinone IIA promotes ferroptosis by inhibiting the KDM1A/PIAS4/SLC7A11 axis, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis[98].

2.2.2. SUMOylation of Mitochondrial-Related Enzymes

During cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI), ferroptosis in renal cells is due to the downregulation of DHODH, a key enzyme in mitochondrial pyrimidine synthesis, and its downstream product CoQH2, which exacerbates cisplatin-induced CoQH2 deficiency and LPO, while also causing mitochondrial dysfunction and SIRT3 SUMOylation. Pre-treatment with the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ can alleviate cisplatin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, SIRT3 SUMOylation, and DHODH acetylation, providing a potential therapeutic approach for AKI[99]. Baicalin (BAI) is a bioactive compound with similar cardioprotective effects to the overexpression of SENP1. Sentrin/SENP1 regulates the deSUMOylation process of SIRT3, enhances mitochondrial quality control, prevents cell death, and ultimately improves diabetic cardiomyopathy[100].

The potential regulatory role of some traditional Chinese medicine components in ferroptosis through protein modification. Delineates the potential mechanisms by which natural phytochemicals from traditional Chinese medicinal herbs modulate ferroptosis-related proteins through various PTMs in disease treatment.

| Modification | Natural Herbs | Targets | Disease | Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination | Curcumin | AR | GBM | AR enhances the drug resistance of GBM to TMZ, and curcumin analog ALZ003-mediated AR ubiquitination causes astrocytoma cells to undergo ferroptosis. | [94] |

| SUMOylation | Baicalin | SIRT3 | DCM | Baicalin is a bioactive compound with similar cardioprotective effects to the overexpression of SENP1. Sentrin/SENP1 regulates the deSUMOylation process of SIRT3, enhances mitochondrial quality control, prevents cell death, and ultimately improves diabetic cardiomyopathy. | [100] |

| Phosphorylation | PrA | ACSL4 and FTH1 | DIC | PrA interacts with ACSL4 and FTH1, thereby suppressing ACSL4 phosphorylation and phospholipid peroxidation, and concurrently inhibiting FTH1 autophagic degradation and Fe²⁺ release. | [118] |

| Phosphorylation | Curcumin | Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a | MIRI | Curcumin attenuates autophagy-dependent ferroptosis induced by myocardial ischemia-reperfusion via the Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway. | [108] |

| Phosphorylation | SFN | Nrf2 | AKI | SFN intervention can interact with Nrf2 and autophagy to prevent ferroptosis in AKI. | [121] |

| Phosphorylation | Bergapten | PI3K | Renal fibrosis | Bergapten, a natural coumarin derivative found in citrus peel, has been reported to inhibit PI3K phosphorylation and indirectly restore GPX4 expression. | [120] |

| Acetylation | Paeoniflorin | p53 | Brain injury | Paeoniflorin promotes p53 ubiquitination and degradation via the proteasome, inhibits p53 acetylation, reduces its stability, and regulates the SLC7A11-GPX4 pathway to inhibit ferroptosis. | [134] |

| Lactylation | Evodiamine | HIF1A histone | Prostate cancer | Evodiamine inhibits the expression of HIF1A histone lactylation in prostate cancer cells, significantly blocking lactate-induced angiogenesis. It further enhances the transcription of the signaling protein Sema3A, suppresses the transcription of PD-L1, and induces ferroptosis through the expression of GPX4. | [212] |

2.2.3. SUMOylation Associated with the Regulation of Immune Responses

Research has elucidated that SUMOylation exerts regulatory influence over ferroptosis and concurrently participates in immune responses. SENP3, identified as a redox-sensitive deubiquitinating protease, assumes a pivotal role in macrophage functionality. SENP3 enhances the susceptibility of macrophages to ferroptosis induced by RSL3, augments ferroptosis in M2 macrophages, and diminishes the proportion of M2 macrophages in vivo. SENP3 interacts with and de-SUMOylates FSP1 at the K162 site, thereby heightening macrophage sensitivity to ferroptosis[101]. In melanoma, a novel circular RNA circPIAS1 encodes a unique 108-amino-acid peptide that significantly impedes immunogenic ferroptosis triggered by immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy by regulating the balance between STAT1 SUMOylation and phosphorylation, revealing a new mechanism of immune evasion in melanoma[102].

2.2.4. SUMOylation Associated with HIF-1α

The novel long non-coding RNA (lnc-HZ06) is capable of concurrently modulating hypoxia (as evidenced by the HIF1α protein), ferroptosis, and miscarriage. Mechanistically, HIF1α-SUMO predominantly functions as a transcription factor to enhance the transcription of NCOA4 in hypoxic trophoblasts. As a transcription factor, HIF1α-SUMO also promotes the transcription of lnc-HZ06, which in turn facilitates the SUMOylation of HIF1α by inhibiting SENP1-mediated de-SUMOylation. Thus, lnc-HZ06 and HIF1α-SUMO form a SUMOylation-related positive feedback regulatory loop[103]. Additionally, HSP70 inhibits ferroptosis through HIF-1α SUMOylation, and the occurrence of lung cancer recurrence subsequent to radiofrequency ablation offers a fresh avenue for exploring therapeutic targets aimed at curbing lung cancer recurrence[101].

2.2.5. SUMOylation Associated with ACSL4

In the context of spinal cord injury, SENP3 serves as a deubiquitinase for TRIM28. The upregulation of TRIM28, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, leads to the conjugation of SUMO3 to lysine 532 of ACSL4. This modification inhibits the K63 ubiquitination of ACSL4, thereby enhancing its stability and increasing cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis. Additionally, a positive feedback loop between oxidative stress and TRIM28 activity further amplifies ferroptosis. The identification of Rutin hydrate as an inhibitor of the TRIM28/ACSL4 axis presents a novel therapeutic avenue for the treatment of spinal cord injury[104].

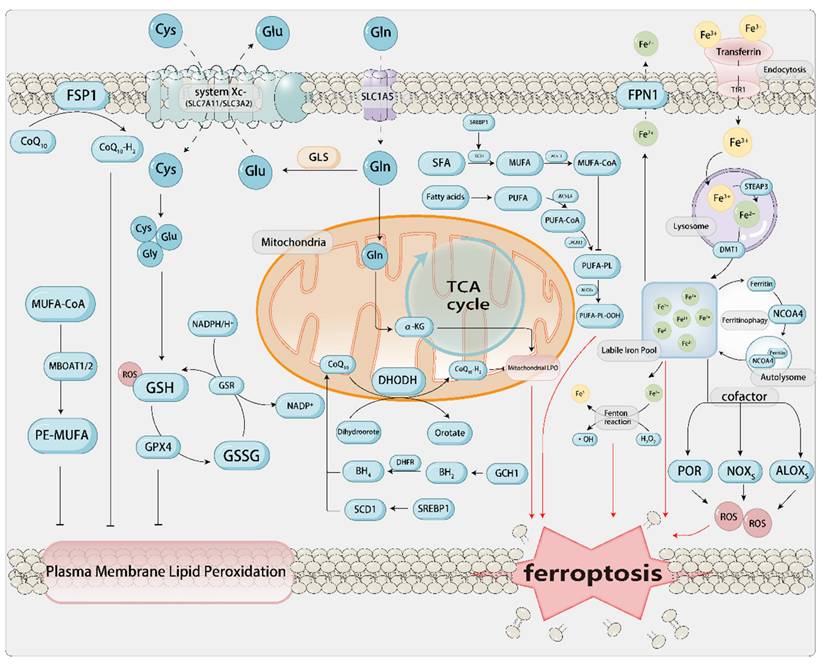

2.3. Phosphorylation

Among the many types of post-translational modifications (PTMs), phosphorylation modification is present in approximately one-third of all proteins and ranks as one of the most prevalent and significant types of modifications. Phosphorylation modulates intracellular signaling, cellular architecture, proliferation, apoptosis, transcriptional activity, and metabolic pathways, and the regulatory ability to adapt to pathogenic microorganisms, among other things. Mechanistically, phosphorylation is the process of transferring the γ-phosphate group from ATP or GTP to the side chain of an amino acid in the substrate protein (commonly occurring at serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues), with ATP and GTP being converted to ADP and GDP, respectively. This is a reversible enzymatic reaction, with enzymes that catalyze protein phosphorylation known as protein kinases (PK), and those that catalyze protein dephosphorylation known as protein phosphatases (PPase). Phosphorylation has been found to play a potential role in regulating many metabolic pathways involved in ferroptosis.[Figure 2]

2.3.1. Phosphorylation in AMPK-Related Pathways

When it comes to phosphorylation, we must mention one of the classic pathways—the AMPK pathway. Adenosine 5'-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK), also known as AMP-dependent protein kinase, is a central modulator of biological energy metabolism and is indispensable for the maintenance of cellular energy homeostasis. AMPK is composed of a catalytic α subunit and regulatory β and γ subunits, forming a heterotrimeric structure. When AMP binds to the γ subunit, it allosterically activates the complex, making it a more susceptible substrate for phosphorylation at the threonine 172 site, which is more easily phosphorylated in the activation loop of the α subunit by the primary upstream AMPK kinase LKB1. AMPK can also be directly phosphorylated at the threonine 172 site by CAMKK2, a response elicited by fluctuations in intracellular calcium levels subsequent to the activation of metabolic hormones such as adiponectin and leptin. As a kinase, the activity of AMPK is regulated by factors such as the organism's energy status, with an increased AMP/ATP ratio being the main factor that activates AMPK. Generally, stress factors such as tissue ischemia and hypoxia lead to the activation of AMPK. Once activated, AMPK primarily regulates various biological processes by phosphorylating its downstream targets. AMPK, functioning as a cellular energy sensor, detects low ATP levels. Once activated, it enhances signal transduction pathways that restore cellular ATP levels, including fatty acid oxidation and autophagy[15].

The phosphorylation in ferroptosis-related proteins. a. Phosphorylation in AMPK-Related Pathways AMPK is a trimeric complex composed of an α catalytic subunit and β and γ regulatory subunits. Stress conditions such as low ATP levels and hypoxia can activate AMPK, enabling it to phosphorylate downstream proteins for regulatory purposes. ACC is involved in fatty acid oxidation and synthesis. AMPK can phosphorylate the T79 site of ACC, rendering it inactive and thereby reducing lipid deposition. Liraglutide can enhance this process. In contrast, PRKCQ-mediated phosphorylation of HPCAL1 at the Thr149 site can activate the autophagic degradation of CDH2. AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of BECN1 at Ser90/93/96 directly blocks system Xc- by binding to SLC7A11, thereby inhibiting the uptake of Cys and enhancing ferroptosis. SIRT3 positively regulates AMPK; activation of SIRT3 depletes the activation of the AMPK-mTOR pathway, thereby inhibiting autophagy. AMPK phosphorylates UMPS at Ser214, which in turn promotes cell resistance to ferroptosis mediated by DHODH. b. Ferritin Autophagy-Related Phosphorylation ATM phosphorylates NCOA4, which dominates the intracellular free iron by promoting the interaction between NCOA4 and ferritin, thereby maintaining ferritinophagy. Meanwhile, the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway can upregulate the expression of NCOA4. c. Phosphorylation Related to ACSL4 Phosphorylation of ACSL4 by PKCβII can promote ferroptosis induced by LPO. In contrast, LHPP interacts with AKT, thereby inhibiting AKT phosphorylation and, consequently, the phosphorylation of ACSL4 at the T624 site. This allows ACSL4 to escape phosphorylation-dependent protein degradation, promoting the accumulation of LPO and ferroptosis. d. Phosphorylation Related to Nrf2-SLC7A11-GPX4 DNA damage-induced ATR can activate the phosphorylation of USP20 at Ser132 and Ser368, thereby enhancing the stability of SLC7A11. SFN activates the Nrf2 signaling pathway and its downstream targets, enhancing cellular autophagy. Nrf2-dependent autophagy activation disrupts the binding of SLC7A11 to BECN1 phosphorylated at the S93 site and increases the membrane translocation of SLC7A11 to counteract ferroptosis.

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) is the rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid metabolism, involved in the oxidation and synthesis of fatty acids, and plays a key role in fatty acid metabolism. During stress in the body, AMPK mediates the phosphorylation of ACC, inactivating it by phosphorylating the threonine at position 79, which promotes fatty acid oxidation, reduces serum free fatty acids, and subsequently decreases lipid deposition in tissues, improving lipid metabolism. Investigations have revealed a significant impact of a modest elevation in ACC phosphorylation by AMPK and the phosphorylation of hippocampal calcium-binding protein-like 1 (HPCAL1) at Thr149 mediated by protein kinase C theta (PRKCQ) can activate the autophagic degradation of cadherin 2 (CDH2) and partially protect cells from erastin-induced cell death[103]. Liraglutide is a human glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog produced by recombinant yeast, used for the treatment of adult type 2 diabetes. Liraglutide not only improves glucose metabolism but also regulates lipid metabolism-related signal transduction, including AMPK and ACC. Mechanistically, Liraglutide mitigates type 2 diabetes-associated non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via AMPK/ACC pathway activation and ferroptosis inhibition[105]. Semaglutide (Smg), a GLP-1 receptor agonist, enhances KLB mRNA expression significantly through the activation of the cAMP signaling pathway, particularly via the phosphorylation of PKA and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB). Subsequently, the AMPK signaling pathway is activated, reprogramming key metabolic processes involved in ferroptosis[106].

AMPK exerts a significant regulatory influence on the autophagy pathway. AMPK can regulate autophagy-dependent ferroptosis by modulating the core autophagy regulatory factors beclin 1 (BECN1, also known as Atg 6) and the mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (MTOR). Studies have found that the activation of the BECN1 pathway increases ferroptosis in CRC cells. AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of BECN1 directly blocks system Xc- by binding to SLC7A11, thereby enhancing ferroptosis. Knocking down BECN1 suppresses ferroptosis triggered by system Xc- inhibitors, including erastin, sulfasalazine, and sorafenib. AMPK-induced BECN1 (Ser90/93/96) phosphorylation is a necessary condition for the formation of the BECN1-SLC7A11 complex and LPO. Inhibition of PRKAA/AMPKα can attenuate erastin-induced BECN1 phosphorylation at S93/96, disrupt BECN1-SLC7A11 complex assembly, and inhibit ensuing ferroptosis[62]. SIRT3 positively modulates AMPK phosphorylation. Studies have found that in gestational diabetes, increased expression of SIRT3 leads to classical ferroptosis events and autophagy. Mechanistically, the activation of SIRT3 depletes the activation of the AMPK-mTOR pathway and enhances GPX4 levels, thereby inhibiting autophagy and ferroptosis. Similarly, the depletion of AMPK also blocks the induction of ferroptosis in trophoblasts. Activation of autophagy via SIRT3 upregulation enhances the AMPK-mTOR pathway and reduces GPX4 levels, thereby inducing ferroptosis in trophoblasts[107]. Curcumin (Cur) inhibits autophagy-dependent ferroptosis via the Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway, thereby maintaining cardiomyocyte function[108]. Piezo1 is a member of the mechanosensitive cation channel family. Studies have found that mice with specific intestinal epithelial Piezo1 deficiency (Piezo1ΔIEC) show significantly diminished intestinal inflammation and enhanced intestinal barrier function relative to wild-type (WT) mice in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. Erastin is capable of reversing the protective impact of Piezo1 silencing on LPS-induced ferroptosis in Caco-2 cells. Mechanistically, Piezo1 has been found to modulate ferroptosis via the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway[109].

Additionally, AMPK can also affect the phosphorylation of metabolic pathways. DHODH reduces CoQ's involvement in pyrimidine metabolism by promoting the oxidation of dihydroorotate (DHO) into orotate. AMPK phosphorylates the Ser 214 site of orotate monophosphate synthase (UMPS) and enhances pyrimidine body assembly, thereby promoting DHODH-mediated resistance to ferroptosis in HeLa cells[110].

Since AMPK is closely related to energy metabolism, and mitochondria are the most important energy factories in cells, they play a significant role in regulating ferroptosis. AMPK is also crucial for regulating mitochondrial homeostasis. Therefore, researchers have compared the main differences between mitochondrial and AMPK functions in ferroptosis. Although mitochondria selectively promote ferroptosis induced by cysteine starvation or erastin, but not by RSL3. However, studies have shown that glucose deprivation or AMPK deficiency sensitizes cells to ferroptosis induced by erastin, RSL3, and cysteine starvation. Thus, energy stress-mediated AMPK activation may inhibit ferroptosis through mitochondrial-independent mechanisms[111]. Nicorandil treatment enhances the phosphorylation of AMPKα1 and promotes its translocation to the mitochondria, thereby inhibiting the mitochondrial translocation of ACSL4, which is typically mediated by mitophagy. Consequently, this process suppresses mitochondria-associated ferroptosis[112].

Due to the multitude of downstream signals of AMPK, this provides more possibilities for targeting the phosphorylation regulation of ferroptosis through AMPK-related pathways. However, related research is still somewhat lacking, and we need more studies on its regulation of energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, and autophagy-related pathways under stress and non-stress conditions.

2.3.2. Ferritin Autophagy-Related Phosphorylation

Ferritin autophagy, a critical component of ferroptosis, is primarily regulated by NCOA4. Mechanistically, NCOA4-mediated ferritin autophagy plays a crucial role in maintaining intracellular iron homeostasis by promoting ferritin transport and iron release[113]. The Ser/Thr kinase ATM serves as the principal detector of DNA double-strand break damage. Studies have reported that ATM phosphorylates NCOA4 to dominate the intracellular unstable free iron, promoting the interaction between NCOA4 and ferritin, thereby maintaining ferritin autophagy[114]. Additionally, the phosphorylation of pathway proteins related to NCOA4 also has a significant impact on ferroptosis. Studies have found that the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway modulates NCOA4 expression. Inhibition or knockdown of STAT3 can effectively reduce NCOA4 levels, protecting H9C2 cells from ferroptosis mediated by ferritin autophagy, while overexpression of STAT3 via plasmids appears to augment NCOA4 expression, culminating in canonical ferroptosis events. The upregulation of phosphorylated STAT3, activation of ferritin autophagy, and induction of ferroptosis also occur in mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD), and are the cause of HFD-induced cardiac damage. Evidence suggests that Piperlongumine, a natural compound, can effectively reduce the levels of phosphorylated STAT3 both in vitro and in vivo, protecting cardiomyocytes from iron autophagy-mediated ferroptosis[115]. Further understanding of NCOA4-mediated ferritin autophagy, as well as the modifications of the NCOA4 protein itself, may help in the development of new therapeutic strategies for diseases involving ferritin autophagy.

2.3.3. Phosphorylation Related to ACSL4

ACSL4 is an important enzyme that induces the occurrence of ferroptosis in the lipid metabolic pathway. The biosynthesis of arachidonyl-CoA catalyzed by ACSL4 contributes to the execution of ferroptosis by triggering phospholipid peroxidation[116]. Studies have found that the phosphorylation of ACSL4 by PKCβII promotes ferroptosis induced by LPO. PKCβII detects initial lipid peroxides and amplifies ferroptosis-associated LPO via ACSL4 phosphorylation and activation, emerging as a crucial ferroptosis mediator. Suppressing the PKCβII-ACSL4 pathway mitigates ferroptosis in vitro and obstructs immunotherapy-induced ferroptosis in vivo[16]. LHPP, a tumor suppressor, modulates diverse signaling pathways via its phosphatase activity, having a key impact on the regulation of tumor cell proliferation and survival. Studies have shown that LHPP interacts with Protein Kinase B (also known as AKT), thereby inhibiting AKT phosphorylation, which in turn suppresses the phosphorylation of ACSL4 at the T624 site. This interaction obstructs phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination, thereby inhibiting SKP2 from recognizing and binding to ACSL4 at the K621 site. Consequently, ACSL4 escapes lysosomal degradation, resulting in its accumulation and the promotion of LPO and ferroptosis[117]. Protosappanin A (PrA) is an active compound extracted from the traditional Chinese medicinal herb, Sappan wood. Recent studies have demonstrated that PrA binds to ACSL4 and FTH1, thereby inhibiting ACSL4 phosphorylation and phospholipid peroxidation, while preventing the autophagic degradation of FTH1 and the release of Fe²⁺[118].

2.3.4. Phosphorylation Related to Nrf2-SLC7A11-GPX4

GPX4 is an important catalytic enzyme in the antioxidant mechanism against ferroptosis. Phosphorylation modifications of GPX4, as well as modifications of system Xc-, which significantly affect the function of GPX4, can regulate ferroptosis. Research has demonstrated that the activation of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) signal activates AKT to phosphorylate CKB at the T133 site, diminishing its metabolic activity while augmenting its interaction and phosphorylation with GPX4 at the S104 site. This mechanism blocks the interaction between HSC70 and GPX4, thereby preventing GPX4 degradation via chaperone-mediated autophagy in mice, inhibiting ferroptosis, and promoting tumor growth[12]. Additionally, investigations have revealed that USP20 is highly expressed in HCC cells exhibiting resistance to OXA. Elevated USP20 levels in HCC correlate with adverse prognostic outcomes. USP20 facilitates OXA resistance and acts as a suppressor of ferroptosis in HCC. Immunoprecipitation results show that the UCH domain of USP20 engages in an interaction with the N-terminus of SLC7A11. USP20 enhances the stability of SLC7A11 by deubiquitinating the K48-linked polyubiquitin chains at the K30 and K37 residues of the SLC7A11 protein. Most importantly, the phosphorylation of USP20 at Ser132 and Ser368 requires the activation of DNA damage-induced ATR. The phosphorylation of USP20 at Ser132 and Ser368 augments its stability, thereby conferring OXA and ferroptosis resistance to HCC cells[119]. Furthermore, certain herbal extracts have been shown to exert therapeutic effects. Bergapten, a natural coumarin derivative found in citrus peel, has been reported to inhibit PI3K phosphorylation and indirectly restore GPX4 expression, thereby suppressing ferroptosis and alleviating renal fibrosis[120].