Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(2):920-950. doi:10.7150/ijbs.124177 This issue Cite

Review

RNA Methylation in Cancer Metabolism: from Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities

1. Department of Colorectal Surgery, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.

2. Department of Clinical Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Oncology, National Cancer Center/National Clinical Research Center for Cancer/Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.

# These authors have made equal contributions to the study.

Received 2025-8-23; Accepted 2025-12-1; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

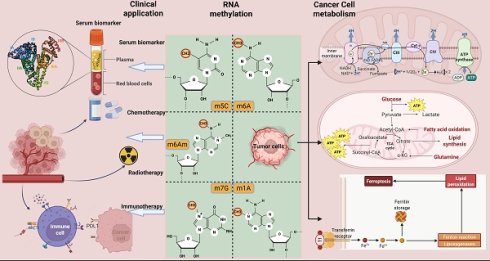

One of the most important changes in the transformation of normal cells into tumor cells is metabolism. In order to satisfy the more active proliferation, migration and metastasis of cancer cells, abnormal changes occur in various pathways and molecules involved in metabolism, which eventually lead to metabolic reprogramming of tumor cells. This process involves the uptake of nutrients and changes in major metabolic forms. As an important part of post-transcriptional epigenetics, RNA methylation modifications can regulate RNA processing and metabolism, while dynamically and reversibly influencing the expression of specific molecules, thereby ultimately affecting diverse biological processes and cellular phenotypes. In this review, various types of RNA methylation modifications involved in cancer are summarized. Subsequently, we systematically elucidate the mechanism of RNA modification for metabolic reprogramming in cancer, including glucose, lipid, amino acid and mitochondrial metabolism. Most importantly, we discuss in depth the clinical significance of RNA modification in metabolic targeted therapy and immunotherapy from mechanism to therapeutic application.

Keywords: RNA methylation, cancer, metabolism, clinical application

1. Introduction

RNA methylation modification first came into human view in the 1950s, when the first structurally modified nucleoside pseudouridine was labeled[1]. Over the following decades, more than 150 different classes of RNA modifications have been validated and discovered on cellular RNA[2]. However, researches on RNA modifications in disease have progressed slowly during this period. The past decade has seen a renaissance in RNA modification research, attracting increasing scientific attention[3]. In particular, in 2023, nucleoside base modification's contribution to the development of an mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 earned it a Nobel Prize that year, greatly inspiring biologists working on RNA-based therapies[4]. The landscape of post-transcriptional regulation is profoundly shaped by RNA modifications, among which RNA methylation stands out as one of the most abundant, reversible, and well-studied epigenetic mechanisms.

Cancer is one of the greatest threats to global public health. Despite significant progress in cancer detection and management, there are still tens of millions of new cancer cases and nearly half of cancer-related deaths occurring each year[5, 6]. A defining feature of cancer is metabolic reprogramming, an adaptive mechanism whereby cancer cells rewire their metabolic circuits to support rapid growth and enhance survival under stressful conditions. This metabolic shift enables the heightened energy generation necessary to fulfill the increased biosynthetic demands of proliferating cancer cells[7]. To achieve and sustain their proliferative advantage, cancer cells must activate or upregulate core metabolic pathways[8]. This phenomenon, characterized by dynamic alterations in metabolic patterns, encompasses several key areas: enhanced glycolysis, accelerated glutamine metabolism, upregulated lipid metabolism, modifications in amino acid metabolism, and mitochondrial adaptations. These metabolic changes are intricately shaped by the interplay between cancer cells and their surrounding tumor microenvironment[9]. Emerging evidence now underscores the role of RNA methylation as a pivotal regulator of this metabolic reprogramming. Functioning as a critical layer of post-transcriptional control, it allows cancer cells to swiftly adjust the expression and activity of metabolic enzymes and oncogenic signaling molecules in response to the fluctuating tumor microenvironment[10].

This review synthesizes current knowledge on major RNA methylation modifications in cancer, with a dedicated focus on their interplay with metabolic reprogramming. Beyond delineating these specific regulatory roles, we critically assess the resulting therapeutic vulnerabilities and potential for targeting the RNA methylation machinery, concluding with a perspective on future research trajectories in this field.

2. The Writer, Reader, and Eraser Enzymes of RNA Methylation

2.1 m⁶A: The most prevalent RNA methylation modification

N6-methyladenosine (m⁶A), a classical and reversible RNA modification, is dynamically regulated by methyltransferases (“writers”) that install the mark and demethylases (“erasers”) that remove it[11]. The functional readout is executed by “reader” proteins, which recognize m⁶A and regulate downstream pathways to implement specific biological functions[12]. The mechanism of the main RNA modifications is illustrated in Fig. 1. m⁶A modification is generated through the co-modification of the methyltransferase complex, which comprises METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, VIRMA, ZC3H13, and RBM15/RBM15B[13]. The METTL3 domain, which exhibits an affinity for S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), transfers activated methyl groups to adenosine residues. METTL14 functions as an RNA-binding platform that facilitates the catalytic activity of METTL3[14]. Other writers, such as METTL16, ZCCHC4, and METTL5, are reported to facilitate the m⁶A modification of small nuclear RNA (snRNA), 28S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and 18S rRNA, respectively[15]. Additionally, fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), which are dioxygenases, depend on Fe (II)/α-ketoglutarate and demethylate adenosine residues that have undergone modification via m⁶A methylation[16]. RNA-binding proteins (readers) can detect and adhere to m⁶A modification sites, regulating the function and structural composition of m⁶A -modified RNAs through diverse mechanisms[17]. Readers comprise various protein families, such as the YT521-B homology domain family (YTHDF), insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs), and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRNPs)[18]. In contrast to YTH family proteins, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, and IGF2BP3 exhibit comparable functions (enhancing mRNA stability and translation)[19]. The m⁶A modification is dynamically regulated by writers that install the mark, erasers that remove it, and readers that interpret it. Specifically, the deposited m⁶A marks are recognized by distinct reader proteins, such as YTHDF1, which promotes the translation of the modified mRNA. In contrast, recognition by YTHDF2 facilitates mRNA decay, thereby collectively enabling dynamic post-transcriptional gene regulation[13].

2.2 m⁵C: The most abundant RNA methylation in eukaryotic transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and rRNAs

5-methylcytidine (m⁵C) is also a prevalent RNA alteration in different types of RNAs, such as cytoplasmic and mitochondrial rRNA and tRNA, mRNA, enhancer RNA (eRNA), and several non-coding RNAs[20]. m⁵C modification is catalyzed by the NOL1/NOP2/SUN domain (NSUN) protein family, which comprises seven distinct members (NSUN1-7)[21]. NSUN2, which is the most extensively investigated writer among the members of the NSUN family, mediates the introduction of m⁵C modifications into various RNAs, such as tRNA, microRNA (miRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), and mRNA[22]. Although NSUN1 and NSUN5 are localized within the nucleolus, they can alter the m⁵C modification of the 28S rRNA within the cytoplasmic milieu[23]. Nakano et al. demonstrated that the methylase NSUN3 initiates m⁵C modification in the mitochondrial tRNA of humans[24]. NSUN4, which is located in the mitochondria, serves as a multifunctional mitochondrial protein that facilitates the methylation of 12S rRNA and promotes the assembly of mitoribosomes[25]. Liu et al. structurally characterized NSUN6 in its apo form and after forming a complex with a full-length tRNA substrate. Furthermore, NSUN6 functions as a methyltransferase with specificity toward mRNA[26]. Selmi et al. reported that NSUN7 mediates the incorporation of m⁵C modifications into eRNA[27]. In contrast to m⁵C writers, limited studies have examined the erasers and readers of m⁵C modification. Previous studies have reported that ten-eleven translocation proteins (TETs) are m⁵C demethylases for DNA and mediate the conversion of m⁵C modification[28]. ALKBH1, a well-known eraser, can convert m⁵C modification into two modified forms at position 34 of both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNAs[29]. The RNA-binding protein ALY/REF export factor (ALYREF) is a selective reader of m⁵C. ALYREF exhibits a specific affinity for the 5' and 3' regions of mRNA and regulates the transportation of mRNA from the nucleus[30]. Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1), which is localized to the cytoplasm, functions as a reader that augments the stability of m⁵C-modified mRNAs[31]. The m⁵C modification is installed by writers (e.g., NSUN2) and interpreted by readers to direct diverse molecular outcomes. In mRNA, ALYREF recognizes m⁵C to promote nuclear export, facilitating protein synthesis. Whereas on tRNA, m⁵C deposition by NSUN2 and DNMT2 safeguards structural integrity and prevents degradation, thereby guaranteeing translational accuracy. This regulatory system is dynamically antagonized by erasers like TET proteins, which catalyze the reversal of m⁵C marks[32].

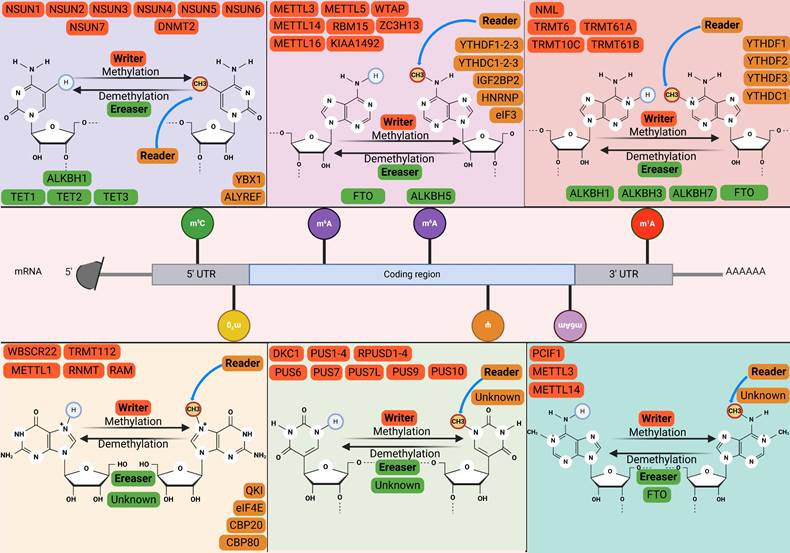

Overview of RNA methylation regulatory mechanisms. RNA methylation represents a dynamic and reversible epigenetic modification process. The major RNA methylation types include m⁶A, m¹A, m⁶Am, m⁷G and m⁵C. This modification process is precisely regulated by three functional protein groups: methyltransferases (writers, orange), demethylases (erasers, green), and recognition factors (readers, yellow), which collectively maintain the homeostasis of RNA methylation. m⁶A methylation: m⁶A methyltransferases catalyze the transfer of methyl groups to N6-adenosine residues on RNA. Conversely, demethylases, including FTO and ALKBH5, dynamically remove m⁶A modification sites from RNA, thereby attenuating the effects of methylation to varying degrees. Furthermore, m⁶A readers specifically recognize and bind to m⁶A-modified nucleotides, thereby activating or inhibiting downstream regulatory pathways. m⁵C methylation: m⁵C is catalyzed by writer proteins, primarily DNMT2 and members of the NSUN family, which deposit m⁵C modifications across diverse RNA transcripts. The removal of m⁵C methylation is mediated by eraser proteins, including TET1-3 and ALKBH1, which facilitate its demethylation. These dynamically regulated m⁵C modifications are recognized by reader proteins such as YBX1 and ALYREF, which subsequently influence RNA processing, stability, and nuclear export. m¹A Methylation: m¹A methylation is catalyzed by distinct methyltransferase complexes with specific substrate preferences. The TRMT6/61A complex recognizes a GUUCRA tRNA-like motif and promotes m¹A methylation at specific sites within mRNAs. TRMT61B mediates m¹A modification on mitochondrial mRNA transcripts, while TRMT10C methylates the A9 position of mitochondrial tRNALys and the m¹A site at position 1374 in ND5 mt-mRNA. The functions of demethylases and reader proteins in m¹A methylation are analogous to those characterized in the m⁶A methylation system. m⁶Am Methylation: PCIF1 specifically recognizes the 5'cap structure of mRNA and exhibits m⁶Am methyltransferase activity. METTL4 is capable of catalyzing m⁶Am methylation at specific sites in U2 snRNA and regulates pre-mRNA splicing. In terms of eraser, m⁶Am is preferentially and specifically demethylated only by FTO. To date, no dedicated reader proteins for m⁶Am have been reported. m⁷G Methylation: The METTL1/WDR4 complex primarily targets internal sites of mRNAs, the G46 position of tRNAs, and G-quadruplex structures within miRNAs. Meanwhile, the WBSCR22/TRMT112 complex predominantly catalyzes m⁷G modification on 18S rRNA, thereby facilitating its maturation. The RNMT and its activator RAM are responsible for the m⁷G modification at the mRNA 5' cap, which subsequently mediates nuclear export and translation initiation of mRNAs.

2.3 m¹A: Associated with m⁶A

N1-methyladenosine methylation (m¹A) modification involves the addition of a methyl group to the first nitrogen atom of adenosine within RNA and was initially considered a major methylation modification for tRNA and rRNA[33]. In contrast to the distribution of m⁶A, m¹A is predominantly localized within the initiation codon and the 5' UTRs[34]. Additionally, m¹A is correlated with m⁶A, which can be partly attributed to the conversion of m¹A to m⁶A through Dimroth rearrangement under alkaline conditions[35]. The human tRNA m¹A methyltransferase, which is commonly referred to as the tRNA methyltransferase 6-tRNA methyltransferase 61A (TRMT6-TRMT61A) complex[36]. The complex serves distinct roles across RNA species. In tRNA, it safeguards structural integrity to ensure translational fidelity and efficiency. Within mRNA, the same mark actively promotes ribosomal translocation during translational elongation[37]. The enzymatic activity of tRNA methyltransferase 10C (TRMT10C) in conjunction with its binding partner protein Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family 5C member 1 (SDR5C1) promotes the introduction of m¹A into mitochondrial tRNA[38]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that ALKBH7 demethylates mitochondrial pre-tRNA. ALKBH1, ALKBH3, and FTO are reported to facilitate the demethylation of tRNA[39, 40]. Additionally, YTHDC1, but not YTHDC2, directly binds to m¹A modification in RNA[41]. However, further studies are needed to elucidate the functional role of YTHDC1.

2.4 m⁷G: Key after-cap regulator

N7-methylguanosine (m⁷G) is a highly conserved RNA modification widely present in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes[42]. The most well-known function of m⁷G modification is its role as the core component of the 5' cap structure (m⁷GpppN) of eukaryotic mRNA[43]. This 'cap' is essential for mRNA stability, nucleocytoplasmic transport, and the initiation of protein translation. However, with advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies, scientists have discovered that m⁷G modification is not confined to the 5' end of mRNA. It is also present internally in various RNA types, including tRNA, rRNA, miRNA, and within internal regions of mRNA[44]. The processes of writing, erasing, and reading m⁷G modifications are precisely regulated by specific enzymatic machinery[45]. The METTL1/WDR4 complex catalyzes m⁷G modifications in a large number of tRNAs and internal mRNA sites, where METTL1 serves as the catalytic subunit and WD repeat domain 4 (WDR4) is an essential auxiliary subunit for its stability and localization[46]. Catalysis is executed by RNA guanine-7 methyltransferase (RNMT) for the mRNA 5' cap during maturation[47], by the METTL1-WDR4 complex internally in tRNAs/miRNAs to prevent cleavage and ensure stability, and by the Williams-Beuren syndrome chromosome region 22 (WBSCR22)/tRNA methyltransferase 112 (TRMT112) complex at specific 18S rRNA sites for ribosomal 40S subunit biogenesis[48]. Although irreversible due to the lack of known erasers, the m⁷G signal is interpreted by readers, exemplified by eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), which binds the mark to regulate downstream processes including mRNA translation and metabolism[49, 50].

3. Dynamic Regulation of Cancer Metabolism by RNA Methylation

This section centers on the pivotal phenomenon of cancer metabolic reprogramming to systematically elucidate the mechanistic basis of RNA methylation in regulating diverse oncogenic processes (Fig. 2).

3.1 RNA modifications regulate glucose metabolism in different cancers

Substantial evidence has demonstrated the involvement of RNA methylation modifications in diverse human malignancies, including gastrointestinal, reproductive, and urinary system cancers. This chapter specifically highlights RNA methylation-mediated regulation of cancer-associated glucose metabolic reprogramming (Table 1).

3.1.1 Role of m⁶A modification in glucose metabolism in digestive system tumors

In the following sections, we will describe the process by which m⁶A modifications are involved in glucose metabolism in digestive system tumors (Fig. 3). In esophageal cancer (EC), METTL3 was found to first increase the m⁶A modification of Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) mRNA, and then recognized by reader YTHDF2 to reduce the expression of APC and promote the expression of β-catenin and Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), thereby promoting glucose uptake and lactate production[51]. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), WTAP mediates m⁶A modification on the lncRNA PDIA3P1, which is then recognized by IGF2BP1 to enhance its stability. Functionally, the stabilized PDIA3P1 acts as a competitive endogenous RNA for miR-152-3p, thereby preventing the degradation of Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) mRNA. Concurrently, it attenuates the interaction between MARCH8 and HK2, reducing HK2 ubiquitination and degradation. Consequently, these dual pathways synergistically enhance glycolysis, leading to increased lactate production and driving malignant progression[52].

The role of RNA methylation in glucose metabolism reprogramming in cancer.

| RNA methylation type | Cancer type | Methylase | Methylation target | Downstream effectors | Role of RNA methylation target | Cell phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m⁶A | ESCC | METTL3↑/YTHDF2↑ | APC | β-catenin/PKM2 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation | [51] |

| m⁶A | ESCC | WTAP↑ | PDIA3P1 | GLUT1 and HK2 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT | [52] |

| m⁶A | GC | METTL3↑ | HDGF | GLUT4 and ENO2 | Oncogene | Proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis | [53] |

| m⁶A | GC | METTL3↑/IGF2BP1↑ | NDUFA4 | ENO1 and LDHA | Oncogene | Proliferation and apoptosis | [54] |

| m⁶A | GC | METTL14↓ | LHPP | HIF1A, GLUT1, C-MYC, PDHK1, PKM2, ALDOL A, ENO1, LDHA, and GLS | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation and metastasis | [55] |

| m⁶A | GC | WTAP↑ | HK2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration | [56] |

| m⁶A | GC | KIAA1429↑ | LINC00958 | GLUT1 | Oncogene | Proliferation | [57] |

| m⁶A | GC | IGF2BP3↑ | c-MYC | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration | [58] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL3↑ | HK2 and SLC2A1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | [59] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL3↑ | GLUT1 | mTORC1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, clonal formation, G1-phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis | [60] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL3↑/YTHDF1↑ | HIF-1α | LDHA | Oncogene | Cell viability | [61] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL3↑ | PTTG3P | YAP1 | Oncogene | Proliferation | [62] |

| m⁶A | p53-WT CRC | METTL14↓/YTHDF2↑ | miR-6769b-3p and miR-499a-3p | SLC2A3 and PGAM2 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation | [63] |

| m⁶A | CRC | KIAA1429↑ | HK2 | / | Oncogene | / | [64] |

| m⁶A | CRC | YTHDF2↑ | circ-0003215 | DLG4 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation and metastasis | [65] |

| m⁶A | CRC | YTHDF1↑/WTAP↑ | FOXP3 | SMARCE1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, metastasis, migration and invasion | [66] |

| m⁶A | HCC | METTL3↑ | PDK4 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | [67] |

| m⁶A | HCC | METTL14↓ | USP48 | SIRT6 | Anti-oncogene | Cell viability, clone formation, and invasion and migration | [68] |

| m⁶A | HCC | ZC3H13↑ | PKM2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion | [69] |

| m⁶A | HCC | FTO↑ | PKM2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, colony formation, and G1/G2 arrest | [70] |

| m⁶A | HCC | ALKBH5↓ | UBR7 | Keap1/Nrf2/Bach1/HK2 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, metastasis, migration and invasion | [71] |

| m⁶A | HCC | YTHDF3↑ | PFKL | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion, and lung metastasis | [72] |

| m⁶A | HCC | IGF2BP2↑ | HK2/SLC2A1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, clone formation | [73] |

| m⁶A | CCA | METTL3↑ | AKR1B10 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and invasion | [74] |

| m⁶A | PAAD | METTL3↑ | HK2 | CaMKII/ERK-MAPK pathway | Oncogene | proliferation, neurometastasis, migration, and invasion | [75] |

| m⁶A | PAAD | YTHDF3↑ | DICER1-AS1 | DICER1/miR-5586-5p/SLC2A1, LDHA, HK2, and PGK1 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation and metastasis | [76] |

| m⁶A | LCA | YTHDF2↑ | 6PGD | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | [77] |

| m⁶A | LCA | YTHDF1↑ | ENO1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | [78] |

| m⁶A | LCA | YTHDF1↑ | c-Myc | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and metastasis | [79] |

| m⁶A | LCA | METTL3↑/YTHDF1↑ | DLGAP1-AS2 | c-Myc | Oncogene | Proliferation | [80] |

| m⁶A | OSCC | IGF2BP3↑ | GLUT1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [81] |

| m⁶A | OSCC | IGF2BP2↑ | HK2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, glycolysis, migration and invasion | [82] |

| m⁶A | BRCA | METTL3↑ | LATS1 | Hippo pathway | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion | [83] |

| m⁶A | BRCA | WTAP↑ | ENO1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | [84] |

| m⁶A | BRCA | ALKBH5↑ | GLUT4 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [85] |

| m⁶A | CESC | IGF2BP2↑ | MYC | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [86] |

| m⁶A | CESC | FTO↓ | HK2 | / | Oncogene | / | [87] |

| m⁶A | OV | WTAP↑ | miR-200 | HK2 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [88] |

| m⁶A | THCA | ALKBH5↓ | circNRIP1 | PKM2 | Oncogene | Proliferation | [89] |

| m⁶A | THCA | FTO↓/IGF2BP2↑ | APOE | IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 | Oncogene | Proliferation | [90] |

| m⁶A | GBM | ALKBH5↑ | G6PD | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | [91] |

| m⁶A | GBM | FTO↑ | PDK1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, TMZ resistance, apoptosis, DNA damage repair, and glycolysis | [92] |

| m⁶A | AML | FTO↑/YTHDF2↑ | PFKP and LDHB | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, apoptosis and G0/G1 arrest | [93] |

| m⁶A | OS | RBM15↑ | HK2, GPI, PGK1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and invasion | [94] |

| m⁶A | ccRCC | IGF2BP1↑ | LDHA | / | Oncogene | / | [95] |

| m⁶A | RCC | METTL14↓ | BPTF | ENO2 and SRC | Oncogene | Metastasis, invasion, migration and EMT | [96] |

| m⁶A | DLBCL | WTAP↑ and IGF2BP2↑ | HK2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest | [97] |

| m5C | TNBC | NSUN2↑ | tRNAVal-CAC | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and clonal formation | [98] |

| m⁵C | Bca | YBX1↑ | TM4SF1 | β-catenin/c-Myc signaling pathway | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and invasion | [99] |

| m⁵C | BCa | ALYREF↑ | PKM2 | HIF-1α/ALYREF/PKM2 | Oncogene | Proliferation | [100] |

| m⁵C | LCA | YBX1↑ | PFKFB4 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, invasion and migration | [101] |

| m⁵C | LCA | NSUN2↑ | ME1, GLUT3 and CDK2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, invasion, migration and angiogenesis | [102] |

| m⁵C | GC | NSUN2↑ | PGK1 | PI3K/AKT pathway | Oncogene | Cell growth, invasion and stemness | [103] |

| m⁵C | CRC | NSUN2↑/YBX1↑ | ENO1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, invasion and metastasis | [104] |

| m⁵C | HCC | NOP2↑ | c-Myc | ENO1, LDHA, PKM2 and TPI1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion and metastasis | [105] |

| m⁵C | HCC | NSUN2↑ | PKM2 | / | Oncogene | proliferation and migration | [106] |

| m⁵C | ICC | ALYREF↑ | PKM2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, invasion and apoptosis | [107] |

| m⁵C | BRCA, PCa, SKCM and CRC | NSUN2↑ | TREX2 | cGAS/STING | Oncogene | Proliferation, cancer stemness and apoptosis | [108] |

| m⁵C | RCC | NSUN2↑ | ENO1 | TOM121/MYC/PD-L1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion and CD8 + T cell infiltration | [109] |

| m⁵C | OC | ALYREF↑ | BIRC5 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis | [110] |

| m⁵C | RB | NSUN2↑ and YBX1↑ | HKDC1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and migration | [111] |

| m⁷G | OSCC | METTL1↑ | tRNA | / | Oncogene | / | [112] |

| m⁷G | EC | METTL1↑ | PFKFB3 | HK2 and LDHA | Oncogene | Proliferation, clonal formation, migration and invasion | [113] |

| m⁷G | LCA | TRMT10C↓ | circFAM126A | HSP90/AKT1 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and apoptosis | [114] |

| m⁷G | Melanoma | METTL1↑ | PKM2 | / | Oncogene | Chemoresistance | [115] |

| m⁷G | CRC | METTL1↑ | PKM2 | CD155 | Oncogene | Proliferation and immunosuppression | [116] |

| m¹A | CESC | ALKBH3↑ | ATP5D | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration | [117] |

| m¹A | TNBC | ALKBH3↑ | ALDOA | / | Oncogene | Chemoresistance | [118] |

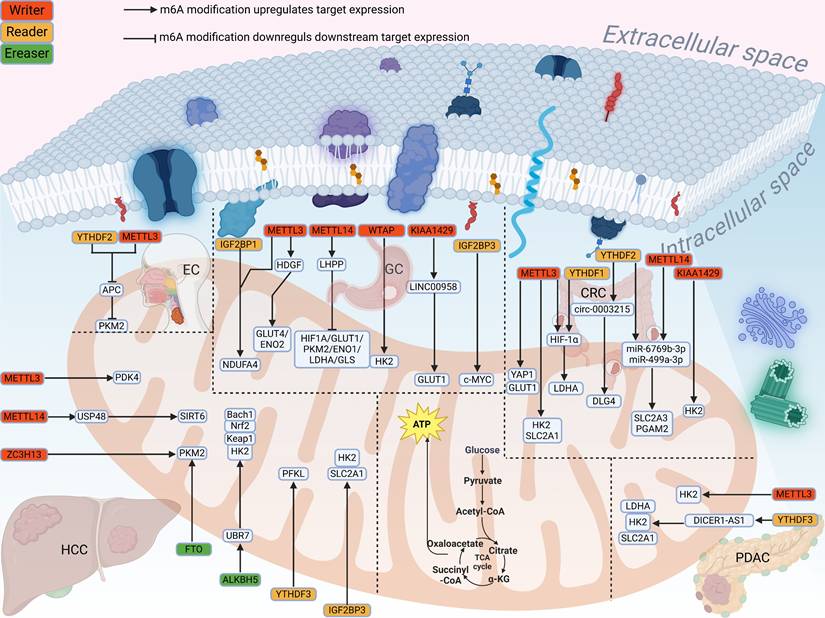

In gastric cancer (GC), Wang et al. found that METTL3 increased the m⁶A modification of HDGF mRNA to promote its expression, and IGF2BP3 further maintained the stability of HDGF mRNA, which in turn activated GLUT4 and ENO2 to enhance glycolysis[53]. Xu et al. confirmed that METTL3 could increase the m⁶A level of NDUFA4 mRNA, and IGF2BP1 further stabilized the expression of NDUFA4 to promote glucose uptake[54]. LHPP is affected by METTL14 to inhibit glycolysis-related proteins, thereby inhibiting aerobic glycolysis[55]. Further studies have shown that overexpression of WTAP enhances glucose uptake, lactate production, and extracellular acidification rate by promoting the stability of HK2 mRNA[56]. It was found that KIAA1429 promoted the remaining level of LINC00958 RNA in an m⁶A dependent manner. And the remaining level of GLUT1 mRNA was further increased, which promoted the aerobic glycolysis[57]. Part of LIN2B binds to c-MYC mRNA, the subsequent upregulated c-MYC increases glucose consumption and promotes glycolysis[58]. Shen et al. demonstrated that lactic acid production and glucose uptake were impaired to varying degrees after METTL3 knockdown. METTL3 regulated HK2 and SLC2A1, increasing the stability and expression of their mRNA[59]. METTL3 also regulates the GLUT1 to mediate glucose metabolism activated the mTORC1 signaling pathway[60], triggers the translation of LDHA mRNA through methylation and recruitment of YTHDF1 to reduce its expression, thus affecting the glycolysis process[61]. Overexpressed LncRNA PTTG3P can promote the glycolysis. METTL3 can enhance the stability of PTTG3P and IGF2BP2 also binds to the m⁶A site to increase its expression[62]. YTHDF2 can bind to SLC2A3 and PGAM1, and thus be positively regulated by METTL14 to increase these two precursor RNAs to weaken glycolysis in p53-WT CRC[63]. KIAA1429 increases the m⁶A modification level of HK2 mRNA and thus promotes its expression, and accelerates glycolysis[64]. circ-0003215 reduces the expression of miR-663b by sponging it, thereby relieving its inhibition of the downstream target DLG4. YTHDF2 binds to circ-0003215 and reduces its m⁶A level leading to a decrease in its expression[65]. In addition, WTAP can activate m⁶A modification by mediating the binding of YTHDF1 to specific sites of FOXP3 mRNA, which further promotes glycolysis by activating the transcription of SMARCE1[66]. METTL3 promotes PDK4 expression and can effectively promote the glycolysis of cancer cells and increase the production of ATP in HCC[67].

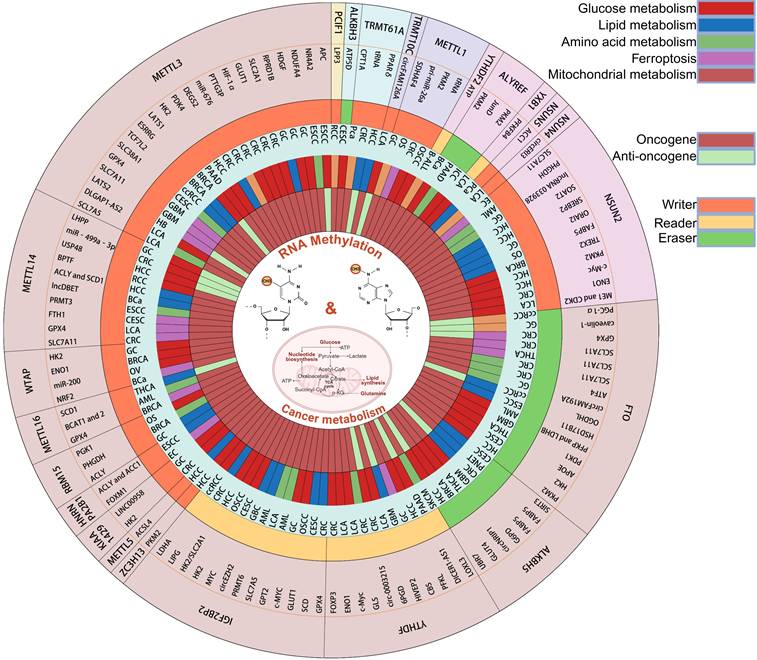

Roles of RNA methylation and downstream targets in cancer metabolism. The RNA methylation modifications can be classified into the following types: m⁶A, m⁵C, m⁷G, m¹A, and m⁶Am. In m⁶A and m⁵C modifications, the enzymes currently known to be associated with cancer metabolism include writers, readers, and erasers, which are represented by orange, yellow, and green colors respectively. For m⁷G and m⁶Am modifications, only writers have been identified to participate in cancer metabolism. Regarding m¹A modification, both writers and erasers are involved in cancer metabolism. The innermost ring displays downstream targets of RNA methylation in cancer, where tumor suppressor genes are shown in green and oncogenes in red. The second outer ring illustrates the metabolic pathways associated with RNA methylation, including glucose metabolism (red), lipid metabolism (blue), amino acid metabolism (green), ferroptosis (purple), and mitochondrial metabolism (orange).

The loss of USP48 can significantly enhance the metabolic flux of aerobic glycolysis. METTL14 stabilizes the mRNA expression of USP48 through m⁶A modification, indirectly participating in this cancer inhibition[68]. ZC3H13 can significantly reduce the stability of PKM2 mRNA, thereby reducing glucose uptake and lactic acid production[69]. FTO knockdown can lead to upregulation of m⁶A modification level, thereby reducing PKM2 mRNA and protein levels and inhibiting aerobic glycolysis[70]. UBR7 can upregulate Keap1 and further inhibits Nrf2/Bach1 pathway, finally inhibits HK2 and glycolysis. Overexpression of ALKBH5 can stabilize the expression of UBR7 mRNA to affect glycolysis[71]. YTHDF3 can promote PFKL mRNA to promote glycolysis. Furthermore, PFKL protein inhibits the ubiquitination of YTHDF3 protein by EFTUD2, thus forming the positive feedback[72]. Ye et al. found that lncRNA miR4458HG can interact with IGF2BP2 to stabilize HK2 and SLC2A1 mRNA. SLC2A1 further encodes GLUT1 to promote the efficiency of glycolysis[73]. METTL3 binds to specific sites on AKR1B10 mRNA and enhances its m⁶A modification level, thereby upregulating AKR1B10 expression. Consequently, the elevated AKR1B10 promotes a glycolytic phenotype in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cells, characterized by increased glucose uptake and lactate production, which ultimately drives malignant progression[74]. Peripheral nerve invasion of the nerves within pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the causes of early metastasis. Li et al. confirmed that neural cells can promote the expression of METTL3 and enhance the glycolytic capacity of PDAC cells by increasing m⁶A modification of HK2 mRNA[75]. lncRNA DICER1 antisense RNA DICER1-AS1 promotes the transcription of DICER1, which further promotes the expression of miR-5586-5p, and subsequently negatively regulated four glycolytic genes, thereby inhibiting the glycolysis. More importantly, YTHDF3 can reduce the stability of DICER1-AS1 from the source[76].

Mechanism of m⁶A methylation in metabolic reprogramming of digestive system tumors. The schematic illustrates the role of m⁶A methylation in metabolic reprogramming of digestive system tumors. Cancer cells predominantly rely on enhanced glycolytic pathways to efficiently generate ATP, meeting the high energy demands associated with tumor growth. This process is primarily achieved through altered tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolism in mitochondria. The arrows indicate genes that promote glucose metabolism, and the blunted lines represent genes that inhibit glucose metabolism. In gastric, colorectal, hepatocellular, and pancreatic cancers, m⁶A writers (including METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, KIAA1429, and ZC3H13) augment m⁶A methylation on downstream target RNAs. Subsequently, m⁶A readers (including YTHDF1-3 and IGF2BP3) recognize the m⁶A modifications on glycolysis-related transcripts and facilitate their transcription, thereby enhancing glycolysis in tumor cells. In contrast, a distinct mechanism is observed in esophageal cancer, where METTL3 mediates m⁶A modification of APC mRNA, and YTHDF2 recognizes and promotes its decay, attenuating APC expression and consequently suppressing cancer progression.

3.1.2 Role of m⁶A modification in glucose metabolism in non-digestive system tumors

High expression of YTHDF2 in lung cancer causes the specific methylation of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (6PGD) mRNA. The upregulation of 6PGD significantly activates the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and promotes the glucose metabolism process[77]. Upregulated METTL3 and downregulated ALKBH5 promote m⁶A modification by binding of ENO1 mRNA, while highly expressed ENO1 activates glycolysis then[78]. Another study found that FTO could significantly inhibit the expression of c-Myc, thus inhibiting the glycolysis. This process is negatively regulated by YTHDF1[79]. METTL3 increased stability of DLGAP1-AS2 by binding to its m⁶A specific site. Upregulated DLGAP1-AS2 promotes the expression of c-Myc to activate aerobic glycolysis in non-small cell lung cancer[80]. IGF2BP3 promotes glycolysis in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells by upregulating the expression of GLUT1[81]. IGF2BP2 was also found to stabilize HK2 mRNA, and the aberrant increase of HK2 promoted the glycolysis[82]. LATS1 can inhibit the glycolysis in breast cancer cells. Overexpression of METTL3 increased the m⁶A modification of LATS1 mRNA, and then YTHDF2 decreased the mRNA stability of LATS1 by recognizing its m⁶A site[83]. In addition, IL1β was found to synergize with TNFα in breast cancer cells to activate ERK1/2 to upregulate the expression of WTAP, which promotes the expression of ENO1 to promote the glycolysis[84]. It was also found that ALKBH5 promotes the demethylation of GLUT4, and decreases the binding of YTHDF2 to the m⁶A site of GLUT4. The upregulation of GLUT4 promotes glycolysis in HER2-targeting-resistant breast cancer cells[85]. Human papilloma virus (HPV) 16 E6/E7 can upregulate IGF2BP2 and recognize MYC mRNA to increase aerobic glycolysis[86]. In addition, FTO inhibits glycolysis in cervical cancer cells by down-regulating HK2 expression[87]. Under hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) upregulates the expression of WTAP, which in turn enhances the proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer (OC) cells. Mechanistically, WTAP significantly increases m⁶A modification on pri-miR-200 and facilitates its processing into mature miR-200 by interacting with DGCR8. Furthermore, studies demonstrate that miR-200 upregulates the key glycolytic enzyme HK2, thereby significantly promoting the Warburg effect within cancer cells[88]. In thyroid cancer, knockdown of ALKBH5 significantly upregulates the expression of circNRIP1 and further upregulates PKM2 to promote glycolysis[89]. APOE, as a carcinogenic agent, promotes glycolysis through the IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. This process is regulated by FTO to reduce the m⁶A modification level of APOE mRNA in thyroid cancer cells[90]. In gliomas, ALKBH5 stabilizes G6PD mRNA by demethylating m⁶A modification sites to activate the PPP[91]. lncRNA JPX increases the stability of PDK1 mRNA in an FTO-dependent manner, thereby promoting glycolysis, proliferation and TMZ resistance in glioblastomas[92]. R-2-hydroxyglutaric acid (R-2HG) effectively inhibits glycolysis in leukemia cells, and this metabolite is used to inhibit downstream targets PFKP and LDHB by inhibiting demethylation from FTO[93]. In osteosarcoma, RBM15 promotes glycolysis by upregulating the expression of three key metabolic enzymes, HK2, GPI, and PGK1[94]. In renal cancer, IGF2BP1 can increase the expression of LDHA and promote glycolysis[95]. Low expression of METTL14 can release the inhibition of BPTF and activate downstream targets ENO2 and SRC, promoting the glycolysis of RCC cells[96]. In Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), piRNA-30473 enhances the stability of WTAP mRNA by binding to its 3' UTR, thereby reducing its decay. The upregulated WTAP, in turn, promotes the expression of HK2 by targeting its transcript's 5' UTR. Concurrently, another reader protein, IGF2BP2, exerts a similar promotional effect on HK2 expression. Collectively, this regulatory axis ultimately leads to increased glycolysis[97].

3.1.3 Roles of other RNA modifications in glucose metabolism in cancers

In recent years, many studies have focused on the metabolic reprogramming involved in m⁵C modification, especially in glucose metabolism. In TNBC, the majority of tRNA m⁵C modifications have a strong positive association with NSUN2 levels, with tRNAVal-CAC exhibiting the most pronounced correlation. Functional assays show that overexpression of NSUN2 and tRNAVal-CAC can significantly enhance glucose uptake, lactate production, and intracellular ATP levels, indicating a promotion of glycolytic metabolism[98]. In BCa cells, knockdown of YBX1 suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasion, while also attenuating glycolytic activity. Mechanistically, this occurs through YBX1-dependent m⁵C modification that enhances the stability of TM4SF1 mRNA. The upregulated TM4SF1 activates the β-catenin/c-Myc signaling pathway, ultimately promoting glycolysis[99]. It was found that ALYREF binds to the m⁵C specific site of PKM2 mRNA to increase its stability, thus promoting the glycolysis process[100]. Yu et al. initially found that THOC3 is capable of promoting glucose utilization rate, lactate production and intracellular ATP levels of LUCS cells. Mechanically, THOC3 exports PFKFB4 mRNA to the cytoplasm, and combines with YBX1 to stabilize its expression[101]. It was reported that NSUN2 significantly upregulated in the lung tissue of mice. It could increase the stability of ME1 and GLU3 mRNAs in an m⁵C dependent manner, resulting in an effect on metabolic reprogramming[102]. In GC, NSUN2 enhances the m⁵C modification on PGK1 mRNA, which is recognized by YBX1, leading to the upregulation of PGK1 and consequently promoting glycolysis. Furthermore, the NSUN2/PGK1 axis activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, ultimately contributing to the development of malignant phenotypes[103]. Similarly, NSUN2 can increase m⁵C modification of ENO1 mRNA, while YBX1 recognizes and stabilizes it. ENO1 then promotes glucose metabolism in CRC cells[104]. In HCC, knockdown of NSUN2 significantly inhibits glycolytic genes such as ENO1, LDHA, PKM2 and TPI1, which is due to the m⁵C modification of c-Myc mRNA[105]. NSUN2 stabilizes PKM2 expression by elevating m⁵C methylation, thereby enhancing glycolytic flux in HCC cells[106]. In intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), ALYREF stabilizes PKM2 mRNA and subsequently promotes glycolytic metabolism[107]. Interestingly, it has been observed that glucose acts as a cofactor for NSUN2 by binding to its N-terminal domain (amino acids 1-28), thereby upregulating its enzymatic activity. The activated NSUN2 then stabilizes TREX2 mRNA, leading to increased TREX2 protein expression and the subsequent inhibition of interferon responses[108]. In RCC, downregulation of NSUN2 diminishes glycolytic capacity by reducing the RNA stability of ENO1. Conversely, NSUN2 overexpression enhances lactate production by upregulating ENO1. The accumulated lactate promotes histone H3K18 lactylation, which in turn upregulates PD-L1 expression via the TOM121/MYC/CD274 signaling axis, ultimately facilitating immune escape[109]. In OC, ALYREF directly interacts with BIRC5, and their expressions are positively correlated. Silencing ALYREF suppresses glycolysis, while the consequent antitumor effects can be rescued by BIRC5 overexpression, indicating BIRC5 functions downstream of ALYREF[110]. In retinoblastoma (RB), NSUN2 depletion impairs glycolysis by reducing the stability of HKDC1 mRNA, which is dependent on its m⁵C modification. This regulatory mechanism is shared by the m⁵C reader YBX1, indicating a coordinated role in promoting HKDC1 expression[111]. In addition to the above two kinds of RNA methylation modifications that have attracted much attention, the deeper regulatory mechanisms of m¹A and m⁷G modifications in cancer have also been gradually discovered. Chen et al. found that elevated METTL1 levels in anlotinib-resistant OSCC cells contributed to enhanced global mRNA translation and stimulated oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) through m⁷G tRNA modification[112]. METTL1 enhances the stability of PFKFB3 mRNA in an m⁷G-dependent manner. Consequently, the up-regulated PFKFB3 augments glycolysis in EC cells by increasing the expression of HK2 and LDHA. This metabolic reprogramming, in turn, contributes to the acquisition of radiotherapy resistance[113]. circFAM126A can bind to HSP90 and promote its ubiquitination to reduce expression, and then inhibit the expression of downstream target AKT1, and finally inhibit glycolysis. This inhibitory effect is due to the fact that TRMT10C increases the stability of circFAM126A in an m⁷G-dependent manner[114]. In melanoma, POU4F1 overexpression induces lactate production and glucose uptake while suppressing the infiltration of anti-tumor immune cells (CD8+ T cells, M1 macrophages, and NK cells), thereby promoting anti-PD-1 resistance. This effect is mechanistically driven by POU4F1-mediated upregulation of METTL1, which increases m⁷G methylation on PKM2 mRNA to enhance glycolysis[115]. METTL1 stabilizes PKM mRNA in a m⁷G-dependent manner, leading to upregulated PKM2 expression. This enhancement drives glycolysis and lactate production. The resulting lactate subsequently induces METTL1 expression, establishing a positive feedback loop that sustains this metabolic circuit[116]. Meanwhile, ALKBH3 promotes the expression of ATP5D to promote the glycolysis process[117]. In Doxorubicin (Dox)-resistant TNBC cells, ALKBH3 elevates m1A enrichment on the 3'UTR of ALDOA mRNA. This modification enhances the stability of ALDOA transcripts without affecting their translation efficiency, thereby boosting glycolysis and conferring greater chemoresistance in these drug-resistant cells[118].

4. RNA Methylation Modifications Regulate Lipid Metabolism in Cancer

Lipid metabolism plays a key role in human growth and development, and abnormal metabolic metabolism of these substances often leads to a variety of diseases[119]. In this section, we emphasized the indelible role of lipid metabolism mediated by RNA methylation in human cancers (Table 2) (Fig. 4).

m⁶A methylation plays an important role in the regulation of lipid metabolism in tumor cells. For example, HNRNPA2B1 promotes the expression of ACLY and ACC1 and induces the synthesis and deposition of lipids in ESCC[120]. FTO affects the expression of HSD17B11 through YTHDF1-mediated m⁶A modification, and low expression of YTHDF1 can increase the expression of HSD17B11 to inducing the formation of lipid droplets in ESCC[121]. METTL3 can increase the stability of RPRD1B mRNA, which can bind to the promoter of c-Jun and c-Fos to activate their expression, and then promote the expression of SREBP1, a key molecule in the synthesis of fatty acids and triacylglycerol[122]. In GC, RBM15 regulates ACLY mRNA in an IGF2BP2-dependent manner, thereby increasing its expression and enhancing tumor cell adipogenesis[123]. In CRC, it was found that IGFBP2 can increase the stability of GPX4 mRNA to promote its expression, and then activate cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS-STING) signaling pathway to inhibit lipid peroxidation[124]. ALKBH5 promotes the expression of FABP5 mRNA in CRC via m⁶A modification. Moreover, FABP5 can interact with fatty acid synthase (FASN) and reduce lipid synthesis[125]. In CRC, IGF2BP1 could increase LIPG mRNA stability to promote lipid metabolism[126]. Guo et al. reported that knockdown of METTL3 reduced the m⁶A modification of DEGS2 mRNA and upregulated its mRNA levels, which further promoted ceramide synthesis[127].

Regulatory mechanisms of RNA methylation in lipid metabolism. (Upper section): m⁶A Modification in Cancer Lipid Metabolism. The m⁶A writers (including METTL3, METTL5, METTL14, RBM15, METTL16 and HNRNPA2B1) and readers (YTHDF1-2 and IGF2BP1-3) upregulate the expression of RNAs involved in lipid metabolism, thereby promoting enhanced lipogenesis. Conversely, the m⁶A eraser FTO and ALKBH5 also upregulate lipid metabolism and facilitates cancer progression. (Lower left quadrant): m⁵C-Mediated Regulation. The m⁵C methyltransferase NSUN2 orchestrates lipid metabolism in Prostate cancer, Gastric cancer (via ORAI2 modulation) and Osteosarcoma (through FABP5 regulation). (Lower right quadrant) m¹A-Dependent metabolic reprogramming in HCC. The writer complex TRMT6/TRMT61A governs lipid metabolic rewiring in hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating the PPARδ signaling axis.

The role of RNA methylation in lipid metabolism reprogramming in cancer.

| RNA methylation type | Cancer type | Methylase and expression in cancer | Methylation target | Downstream effectors | Role of RNA methylation target | Phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m⁶A | ESCC | HNRNPA2B1↑ | ACLY and ACC1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion, tumor size and lymphatic metastasis | [120] |

| m⁶A | ESCC | FTO↑/YTHDF1↓ | HSD17B11 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion, tumor size | [121] |

| m⁶A | GC | METTL3↑ | RPRD1B | c-Jun/c-Fos/SREBP1 | Oncogene | Migration, invasion and lymphatic metastasis | [122] |

| m⁶A | GC | RBM15↑/IGF2BP2↑ | ACLY | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [123] |

| m⁶A/m⁵C | CRC | RBM15B↑, IGFBP2↑ and NSUN5↑ | GPX4 | cGAS-STING signaling pathway | Oncogene | / | [124] |

| m⁶A | CRC | ALKBH5↓ | FABP5 | FASN | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [125] |

| m⁶A | CRC | IGF2BP1↓ | LIPG | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [126] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL3↑/YTHDF2↓ | DEGS2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and migration | [127] |

| m⁶A | HCC | METTL14↑ | ACLY and SCD1 | / | Oncogene | Apoptosis and compensatory proliferation | [128] |

| m⁶A | HCC | METTL5↑ | ACSL4 | / | Oncogene | Migration and invasion, tumor size | [129] |

| m⁶A | GBC | IGF2BP2↑ | circEZH2 | miR-556-5p/SCD1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, G1/S cell cycle arrest, and tumor growth | [130] |

| m⁶A | Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm | ALKBH5↑/IGF2BP2↑ | FABP5 | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | [131] |

| m⁶A | Bladder cancer | METTL14↑ | lncDBET | FABP5/PPARγ | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion, tumor size | [132] |

| m⁶A | ccRCC | FTO↑ | OGDHL | FASN | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis and cell cycle | [133] |

| m⁶A | ccRcc | METTL3↑ | TCF7L2 | FASN, ACC1 and SCD | Oncogene | EMT and metastasis | [134] |

| m⁶A | THCA | METTL16↓/YTHDC2↑ | SCD1 | / | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation and metastasis | [135] |

| m⁶A | CSCC | ALKBH5↓ | SIRT3 | ACC1 | Oncogene | EMT, migration and invasion | [136] |

| m⁶A | Cervical cancer | IGF2BP3↑ | SCD | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion, tumor size and lymphatic metastasis | [137] |

| m⁶A | AML | IGF2BP2↑ | PRMT6 | MFSD2A | Oncogene | Proliferation and apoptosis | [138] |

| m⁶A | Glioma | YTHDF2↑ | LXRα and HIVEP2 | / | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion and tumorigenesis | [139] |

| m⁵C | OS | NSUN2↑ | FABP5 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion, tumor size | [141] |

| m⁵C | GC | NSUN2↑ | ORAI2 | / | Oncogene | Adhesion, migration and invasion | [142] |

| m⁵C | PCa | NSUN5↑ | ACC1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, tumor size | [143] |

| m⁵C | HCC | NSUN2/YBX1↑ | SREBP2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and EMT | [144] |

| m⁵C | HCC | NSUN2↑ | SOAT2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and invasion | [145] |

| m¹A | HCC | TRMT6/TRMT61A↑ | PPARδ | Hedgehog signaling pathway | Oncogene | Tumor size | [147] |

| m¹A | CRC | TRMT61A↑ | tRNA | ACLY | Oncogene | Proliferation and tumor size | [148] |

METTL3/METTL14 can enhance the expression of ACLY and SCD1 through m⁶A modification, thereby activating lipid synthesis and accumulation in liver cancer cells[128]. In addition, METTL5 is upregulated in liver cancer, and the translation of ACSL4 molecule is also promoted to activates lipid synthesis, resulting in increased contents of triglycerides, free fatty acids and cholesterol[129]. In gallbladder cancer (GBC), IGF2BP2 is able to recognize the m⁶A modification site of circEZH2 and stabilize its expression, and subsequently upregulate SCD1 to promote lipid metabolic reprogramming[130]. ALKBH5 is highly expressed in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (pNENs) and promotes the expression of FABP5 by reducing the m⁶A modification degree of FABP5 mRNA at 5'UTR. Subsequently, FABP5 causes lipid accumulation in pNENs via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis[131]. In bladder cancer, METTL14 can bind to the specific sites of lncRNA DBET, and enhance its stability. lncDBET then activates the expression of FABP5 and PPARγ to promote the synthesis and deposition of lipid[132]. FTO specifically reduces the m⁶A modification of OGDHL mRNA and reduces its expression. Low expression of OGDHL leads to the accumulation of molecules such as triglycerides and saturated fatty acids[133]. Another study on ccRCC indicates that HIF2α can activate the expression of METTL3, thereby increasing the m⁶A modification of TCF7L2 mRNA, and recognized byYTHDC1 to promote lipid metabolism[134]. METTL16 can enhance the m⁶A modification of SCD1 mRNA and enable it to be recognized by YTHDC2, thereby reducing the expression and weakening the abnormal lipid metabolism in thyroid cancer[135]. In cervical cancer, the downregulation of SIRT3 caused by ALKBH5 leads to the inhibition of the deacetylation process of ACC1, thereby causing the inhibition of synthesis and accumulation of free fatty acids[136]. IGF2BP3 specifically binds to the m⁶A modification site of SCD mRNA in CESC, thus promoting the contents of triglyceride, palmitoleic acid and oleic acid[137]. In addition, IGF2BP2 can increase the expression of PRMT6 mRNA to inhibit MFSD2A, thereby promoting the lipid metabolism of leukemia stem cells (LSCs)[138]. Upregulated YTHDF1 can inhibit the effluence of cholesterol in gliomas cells and promote the intake of cholesterol by inhibiting the expression of LXRα and HIVEP2[139]. Lipid metabolism mediated by RNA methylation plays a crucial role in tumors, especially in promoting the process of lipid synthesis and deposition in tumor cells[140]. Knockdown of NSUN2 can reduce the m⁵C methylation modification of FABP5 and inhibit its expression to weaken the metabolic process of fatty acids in osteosarcoma cells[141]. Omental adipocytes provide fatty acids to peritoneal metastatic gastric cancer cells, thereby activating the AMPK signaling pathway to augment transcription factor E2F1 expression, which in turn upregulates NSUN2. NSUN2 induces m⁵C methylation on ORAI2 mRNA, with these modification sites being recognized by YBX1 to facilitate the stabilization[142]. In prostate cancer, it was found that phosphorylated NSUN5 activates m⁵C modification of ACC1 mRNA, promoting lipid synthesis and deposition[143]. NSUN2 promotes SREBP2 expression by increasing its m⁵C modification in an YBX1-dependent manner, and then promotes cholesterol metabolism in HCC cells[144]. NSUN2-mediated m⁵C modification of SOAT2 promotes cholesterol biosynthesis, facilitating metabolic reprogramming in HCC cells[145]. The m¹A methyltransferase complex formed by TRMT6 and TRMT61As is an important complex in the m¹A modification process[146]. In liver cancer, TRMT6/TRMT61A can promote the cholesterol synthesis process by promoting the translation process of PPARδ mRNA through m¹A modification[147]. Miao et al. initially discovered that the expression of TRMT61A in CRC tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells was inhibited. Mechanically, TRMT61A can increase the translation of ACLY and further increase the biosynthesis of cholesterol in CD8+T cells[148].

5. RNA Methylation Modifications Regulate Amino Acid Metabolism in Cancer

Amino acid metabolism plays an important role in energy production, maintenance of redox homeostasis, proteins and nucleotide synthesis in cancer cells (Table 3). Increased metabolism of glutamine in tumor cells can provide sufficient energy and substrates used for synthesis for tumor cell proliferation[149].

In GC, FTO removes the methylation site of circFAM192A to protect it from degradation, and then circFAM192A directly binds to SLC7A5 to enhance the stability, which ultimately promotes leucine uptake[150]. In addition, YTHDF1 promotes glutaminase (GLS) protein synthesis by recognizing GLS mRNA, and then promotes the uptake of glutamine in CRC[151]. Han et al. found that YTHDF2 could recognize and bind to ATF4 mRNA, thereby reducing its expression. However, inhibition of glutaminolysis could further upregulate FTO to reduce the m⁶A modification of ATF4 mRNA and avoid the recognition of reader and stabilizing its expression[152]. It has also been found that FTO enhances the expression of SCL7A11 and GPX4 mRNA, thereby enabling the transport of extracellular cysteine into intracellular cysteine, and converting cysteine into oxidized glutathione (GSSG)[153]. In lung cancer, METTL3 promotes glutamine metabolism by upregulating SCL7A5 expression[154]. Another study found that SLC7A5 is recognized and upregulated by IGF2BP2, thereby increasing methionine transport[155]. RBM15 was found to upregulate the expression of serine and glycine metabolism-related proteins by recognizing their mRNAs and promote the progression in breast cancer[156].

The role of RNA methylation in amino acid metabolism reprogramming in cancer.

| RNA methylation type | Cancer type | Methylase | Methylation target | Downstream effectors | Role of RNA methylation target | Types of metabolites | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m⁶A | GC | FTO↑ | circFAM192A | SCL7A5 | oncogene | leucine | [150] |

| m⁶A | CRC | YTHDF1↑ | GLS | / | oncogene | glutamine | [151] |

| m⁶A | CRC | YTHDF2↓ | ATF4 | mTOR | oncogene | glutamine | [152] |

| m⁶A | CRC | FTO↑ | SCL7A11 | GPX4 | oncogene | cysteine, glutamic acid | [153] |

| m⁶A | LCA | METTL3↑ | SCL7A5 | / | oncogene | glutamine | [154] |

| m⁶A | LCA | IGF2BP2↑ | SLC7A5 | AKT/mTOR pathway | oncogene | methionine | [155] |

| m⁶A | BRCA | RBM15↑ | PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH, and SHMT2 | / | oncogene | serine and glycine | [156] |

| m⁶A | CESC | METTL3↑ | SLC38A1 | / | oncogene | glutamine | [157] |

| m⁶A | UCEC | METTL14↑ | PRMT3 | / | oncogene | arginine | [158] |

| m⁶A | Melanoma | YTHDF3↑ | LOXL3 | / | oncogene | lysyl | [159] |

| m⁶A | AML | IGF2BP2↑ | MYC, GPT2, and SLC1A5 | / | oncogene | glutamine | [160] |

| m⁶A | AML | METTL16↑ | BCAT1 and BCAT2 | / | oncogene | Valine, leucine and isoleucine | [161] |

| m⁶A | ESCC | METTL3↑ | NR4A2/IGF2BP2 | / | oncogene | methionine | [162] |

| m⁶A | DLBCL | YTHDF2↑ | ACER2 | SphK/S1P/PI3K/AKT pathway | oncogene | ceramide | [163] |

| m⁵C | GC | NSUN2↑ | lncRNA NR_033928 | GLS | oncogene | glutamine | [164] |

| m⁵C | PAAD | ALYREF↑ | JunD | SLC7A5/mTOR1 | oncogene | large neutral amino acids | [166] |

| m⁵C | AML | NSUN2↑ | PHGDH and SHMT2 | / | oncogene | serine and glycine | [167] |

In cervical cancer, it was found that METTL3 increased the metabolism of glutamine in cervical cancer cells through m⁶A methylation of SLC38A1 mRNA[157]. In addition, METTL14 protects endometrial cancer cells from ferroptosis by regulating arginine methylation through binding to PRMT3[158]. YTHDF3 promotes the expression of lysyl oxidase LOXL3 by recognizing its methylated sites in melanoma[159]. IGF2BP2 upregulates the expression of key genes in glutamine metabolism (MYC, GPT2, and SLC1A5) in an m⁶A-dependent manner to promote AML progression[160]. METTL16 upregulates the expression of the branched-chain amino acid transaminases BCAT1 and BCAT2 in an m⁶A-dependent manner, which in turn regulates BCAA metabolism[161]. ESCC cells consume exogenous methionine to produce SAM, which in turn provides a substrate for m⁶A modification. Methionine and SAM increase the m⁶A modification in the 3'-UTR of NR4A2 via METTL3, thereby promoting its expression[162]. YTHDF2 overexpression exhibits oncogenic properties in DLBCL by promoting a ceramide metabolic axis. Specifically, YTHDF2 enhances the stability and expression of ACER2 through m⁶A-dependent regulation. This leads to accelerated hydrolysis of ceramide to sphingosine, and its subsequent conversion by Sphingosine kinase (SphK) to S1P, which activates pro-survival ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling, driving tumorigenesis. The malignant phenotype in DLBCL cells is effectively suppressed by the addition of exogenous ceramide in vitro[163].

In addition to m⁶A methylation, m⁵C methylation, as one of the most important RNA methylation modifications, also plays a role in various cancers[32]. In GC, NR_03392 enhances glutamine metabolism by acting as a scaffold for the IGF2BP3/HUR complex to maintain the mRNA stability of GLS. Interestingly, as a result of elevated glutamine metabolism, accumulation of its metabolite α-KG can positively feedback increase the expression of NR_03392 by demethylating its promoter[164]. Aberrant accumulation of α-KG has been shown to act as a cofactor for DNA demethylases (TETs) and histone demethylases (JMJDs) in regulating the expression of cancer-associated genes, which is one way in which amino acid metabolites exert carcinogenic effects[165]. In pancreatic cancer, ALYREF indirectly promotes the transcription of SLC7A5 by up-regulating JunD in an m⁵C-dependent manner to regulate the amino acid metabolism[166]. In AML, NSUN2 stabilizes the mRNA of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) and SHMT2—two key enzymes in the serine/glycine biosynthesis pathway—by regulating m⁵C modification, thereby enhancing the expression of PHGDH[167]. In-depth studies to understand the role of RNA methylation modifications in amino acid metabolism will provide new insights for cancer diagnosis and treatment[168].

6. RNA Methylation Modifications Regulate Other Metabolisms in Cancers

In addition to participating in the metabolic regulation of the three major nutrients in the carcinogenic process, RNA methylation modification can also affect cancer progression by regulating other types of metabolism, such as mitochondrial metabolism and iron metabolism (Table 4).

Ferroptosis is a new type of iron-dependent programmed cell death. Under the action of ferric or ester oxygenase, unsaturated fatty acids with high expression on cell membrane undergo lipid peroxidation, which induces cell death[169]. In GBM, knockdown of C5aR1 can reduce the expression of METTL3, thus weakening the m⁶A modification of GPX4 mRNA and triggering the occurrence of ferroptosis[170]. METTL14 can reduce the stability and expression of FTH1 mRNA in an m⁶A dependent manner, indirectly causing the inhibition of downstream PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, thereby relieving the inhibition of ferroptosis[171]. In non-small cell lung cancer cells, METTL14 enhances mRNA stability of GPX4 to inhibit the ferroptosis[172]. In breast cancer, METTL16 can stabilize the expression of GPX4 by increasing its m⁶A methylation, and GPX4 further reduces the levels of intracellular iron, Fe2+ and lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS), inhibits the occurrence of ferroptosis[173]. In EC tissues, HNRNPA2B1 binds to the 3'UTR of FOXM1 mRNA and stabilizes its expression. FOXM1 further binds to the LCN2 promoter and positively regulates the expression to inhibit ferroptosis[174]. In bladder cancer, WTAP can increase m⁶A methylation on the 3'UTR of endogenous antioxidant NRF2 RNA, and subsequently YTHDF1 recognizes the m⁶A site on NRF2 mRNA and enhances NRF2 mRNA stability, inhibiting ferroptosis[175]. HIF-1α induces the lncRNA-CBSLR, which scaffolds the formation of a ternary complex with YTHDF2 and CBS mRNA. This complex promotes CBS mRNA decay, leading to reduced ACSL4 methylation. The hypomethylated ACSL4 protein then undergoes polyubiquitination and degradation, ultimately suppressing ferroptosis[176]. As a reader, NKAP can inhibit ferroptosis in GBM.

The role of RNA methylation in other metabolism reprogramming in cancer.

| RNA methylation type | Cancer type | Methylase | Methylation target | Downstream effectors | Role of RNA methylation target | Phenotype | Metabolic type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m⁶A | GBM | METTL3↑ | GPX4 | / | Oncogene | Tumor size | Ferroptosis | [170] |

| m⁶A | CESC | METTL14↓ | FTH1 | PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | Oncogene | Chemoresistance | Ferroptosis | [171] |

| m⁶A | NSCLC | METTL14↑ | GPX4 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | Ferroptosis | [172] |

| m⁶A | BRCA | METTL16↑ | GPX4 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and tumor size | Ferroptosis | [173] |

| m⁶A | EC | HNRNPA2B1↑ | FOXM1 | LCN2 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration and invasion | Ferroptosis | [174] |

| m⁶A | BCa | WTAP↑ | NRF2 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | Ferroptosis | [175] |

| m⁶A | GC | YTHDF2↑ | CBS | ACSL4 | Oncogene | Tumor size | Ferroptosis | [176] |

| m⁶A | GBM | METTL3↑ | SLC7A11 | / | Oncogene | Tumor size | Ferroptosis | [177] |

| m⁶A | THCA | FTO↓ | SCL7A11 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, invasion and migration, and Ferroptosis | Ferroptosis | [178] |

| m⁶A | CRC | FTO↑ | SCL7A11 | GPX4 | Oncogene | Tumor size | Ferroptosis | [153] |

| m⁶A | CRC | FTO↑ and YTHDF2↓ | GPX4 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | Ferroptosis | [179] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL14↓ and YTHDF2↓ | SLC7A11, SLC3A2, HOXA13, and GPX4 | / | Oncogene | Apoptosis | Ferroptosis | [180] |

| m⁶A | HB | METTL3↑ and YTHDF2↑ | LATS2 | YAP1/ATF4/PSAT1 | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation | Ferroptosis | [181] |

| m⁵C | EC | NSUN2↑ | SLC7A11 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and tumor size | Ferroptosis | [182] |

| m⁵C | GC | NSUN2↑ | GCLC | / | Oncogene | Cell viability | Ferroptosis | [183] |

| m⁵C | AML | NSUN2↑ | FSP1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | Ferroptosis | [184] |

| m⁵C | AML | ALKBH3↑ | ATF4 | SLC7A11, GPX4 and FTH1 | Oncogene | Proliferation and apoptosis | Ferroptosis | [185] |

| m⁵C | HCC | NSUN2↑ and ALYREF↑ | MALAT1 | ELAVL1/SLC7A11 | Oncogene | Proliferation and Chemoresistance | Ferroptosis | [186] |

| m⁵C | HCC | YBX1↑ | RNF115 | DHODH | Oncogene | Proliferation | Ferroptosis | [187] |

| m⁵C | NSCLC | NSUN2↑ | NRF2 | GPX4 and FTH1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and invasion | Ferroptosis | [188] |

| m⁷G | OS | METTL1↓ | pri-miR-26a | FTH1 | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion and tumor growth | Ferroptosis | [189] |

| m⁶A | ccRCC | FTO↓ | PGC-1α | / | Anti-oncogene | Cell growth and apoptosis | Mitochondrial metabolism | [191] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL3↑ | miR-676, miR-483, and miR-877 | ATP5I, ATP5G1, ATP5G3 and CYC1 | Oncogene | Cell proliferation and apoptosis | Mitochondrial metabolism | [192] |

| m⁶A | CRC | METTL14↓ | pri-miR-17 | MFN2 | Oncogene | Proliferation and apoptosis | Mitochondrial metabolism | [193] |

| m⁶A | GC | FTO↑ | caveolin-1 | / | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation, migration, and invasion | Mitochondrial metabolism | [194] |

| m⁶A | OC | IGF2BP1↑ | FTH1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and migration | Mitochondrial metabolism | [195] |

| m⁶A | OC | WTAP↑ and IGF2BP3↑ | ULK1 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and migration | Mitochondrial metabolism | [196] |

| m⁶A | SCLC | METTL3↑ | DCP2 | Pink1-Parkin | Anti-oncogene | Proliferation | Mitochondrial metabolism | [197] |

| m⁵C | LCA | NSUN4↑ | circERI3 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation, cell viability, migration, cell cycle and apoptosis | Mitochondrial metabolism | [198] |

| m⁵C | LCA | NSUN2↑ | circRREB1 | HSPA8/PINK1/Parkin | Oncogene | Proliferation, cell viability, migration, cell cycle and apoptosis | Mitochondrial metabolism | [199] |

| m⁵C | B cell malignancies | YTHDF2↑ | ATP | / | Oncogene | Proliferation | Mitochondrial metabolism | [200] |

| m⁶Am | RCC | PCIF1↑ | LPP3 | / | Oncogene | Proliferation and migration | Mitochondrial metabolism | [201] |

| m⁷G | GC | METTL1↑ and WDR4↑ | SDHAF4 | SDHA and SDHB | Oncogene | Proliferation, migration, invasion, colony formation, and anti-apoptotic abilities | Mitochondrial metabolism | [202] |

| m¹A | PCa | TRMT61A↑ | p-PI3K, CPT1A and CPT1B | / | Oncogene | Colony formation ability, migration and invasion | Mitochondrial metabolism | [203] |

Specifically, NKAP can recognize the 5ʹ-UTR of SLC7A11 mRNA and bind to it to stabilize its expression and increase the protein level of SLC7A11[177]. Similarly, the regulation of SCL7A11 by FTO was found to affect glutamine metabolism in thyroid cancer cells to protect the cells from ferroptosis[178]. It was also found that inhibition of SCL7A11 and GPX4 induced ferroptosis in CRC cells. FTO protected CRC cells from ferroptosis by upregulating SCL7A11 and GPX4 through demethylation[153]. In addition, FTO can co-regulate the methylation modification of GPX4 with YTHDF2 to promote the ferroptosis of colorectal cells to play an oncogenic role[179]. Curdione, as a drug, was found to promote ferroptosis in cancer cells by up regulating the expression of METTL14 and YTHDF2, which in turn affected the expression levels of SLC7A11, SLC3A2, HOXA13 and GPX4[180]. In hepatoblastoma, METTL3 and YTHDF2 inhibit the occurrence of ferroptosis by recognizing the methylation site of LATS2 to promote its degradation, which in turn inhibits the YAP1/ATF4/PSAT1 axis[181]. It has been found that NSUN2 increases m⁵C modification of SLC7A11 mRNA in endometrial cancer, thereby maintaining its stability, and the subsequent increased m⁵C modification is recognized by YBX1 and further participates in mRNA stabilization. Ultimately, SLC7A11 promotes malignant progression by inhibiting ferroptosis[182]. Moreover, lactylation upregulates the catalytic activity of NSUN2, leading to enhanced m⁵C modification and stability of GCLC mRNA, which promotes GSH synthesis and ultimately protects gastric cancer cells from ferroptosis[183]. In AML, deficiency of NSUN2 leads to downregulation of both FSP1 mRNA and protein, consequently sensitizing AML cells to ferroptosis. This heightened sensitivity to ferroptotic inducers can be effectively rescued by FSP1 overexpression. As anticipated, the NSUN2 inhibitor MY-1B recapitulates this effect and demonstrates significant anti-leukemic activity[184]. In addition, ALKBH3 promotes ATF4 expression by demethylating m1A modifications on its mRNA. Consequently, ALKBH3 knockdown diminishes ATF4 levels, resulting in the transcriptional downregulation of key ferroptosis regulators (SLC7A11, GPX4, FTH1) and ultimately suppressing ferroptosis in AML[185]. NSUN2 and ALYREF promote sorafenib resistance in HCC by orchestrating an m⁵C-dependent axis centered on the lncRNA MALAT1. Specifically, they stabilize MALAT1, which enables the cytoplasmic translocation of ELAVL1. This relocalized ELAVL1 then stabilizes SLC7A11 mRNA, thereby suppressing ferroptosis[186]. Moreover, NSUN2-mediated m⁵C modification of RNF115 mRNA is recognized by YBX1, thereby enhancing its translation, the increased RNF115 then suppresses ferroptosis by promoting K27-linked ubiquitination and autophagic degradation of DHODH[187]. In NSCLC, NSUN2 introduces m⁵C modifications within the 5'UTR of NRF2 mRNA, thereby enhancing its stability. Subsequently, the reader protein YBX1 recognizes and binds to these m⁵C sites, further promoting the upregulation of NRF2 mRNA levels. Consequently, this NSUN2/YBX1-NRF2 axis ultimately enhances ferroptosis resistance in NSCLC cells[188]. He et al. found that overexpression of METTL1 led to an increase in mature miR-26a-5p, which further targeted FTH1 mRNA. The reduction of FTH1 significantly increases lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis[189].

Mitochondrial metabolism also plays a critical role in tumor development. In addition to the most basic function of ATP production, mitochondria are able to provide substrates for anabolic metabolism through apoptosis, and mitochondria are able to generate ROS as well as promote RCD signaling for tumor progression[190]. In ccRCC, FTO promotes the expression of PGC-1α mRNA by reducing the m⁶A methylation level, thereby inducing an increase in mitochondrial activity and ROS generation[191]. In CRC, it has been discovered that RALY, as an RNA-binding protein, can facilitate the post-transcriptional processing of specific miRNAs, such as miR-676, miR-483, and miR-877 with METTL3, thereby leading to increased ATP production and decreased ROS levels within CRC cells[192]. Reduced METTL14 decreases m⁶A modification on pri-miR-17, impairing YTHDC2 binding and subsequently increasing pri-miR-17 stability and mature miR-17-5p levels. The elevated miR-17-5p in turn suppresses MFN2, resulting in diminished mitochondrial fusion, increased fission, and enhanced mitophagy, collectively promoting 5-FU resistance in CRC cells[193]. Additionally, the latest research indicates that FTO can promote the degradation of caveolin-1 through demethylation. Depletion of caveolin-1 significantly increases intracellular ATP levels, ATP synthase activity, and cellular OCR in GC cells. However, in FTO-deficient GC cells, caveolin-1 leads to an increased proportion of mitochondrial fragments, thereby suppressing mitochondrial respiration[194]. In OC cells, lncRNA CACNA1G-AS1 upregulates IGF2BP1 expression and enhances FTH1 expression via m⁶A methylation. Following CACNA1G-AS1 knockdown, mitochondrial volume significantly decreases, accompanied by mitochondrial membrane rupture and cristae disappearance. These findings indicate that CACNA1G-AS1 suppresses mitophagy through the IGF2BP1-FTH1 axis[195]. WTAP upregulates ULK1 expression by enhancing its m⁶A modification. IGF2BP3 recognizes these m⁶A sites and stabilizes ULK1 mRNA, which in turn enhances mitophagy, thereby promoting proliferation and migration of OC cells[196]. In SCLC, METTL3 overexpression increases m⁶A modification of DCP2, resulting in downregulation of DCP2 protein. This downregulation in turn impairs the degradation of Pink1 and Parkin, enhances mitophagy, and ultimately confers chemotherapy resistance[197].

Recent research indicates that NSUN4 upregulates the expression and nuclear export of circERI3 via m⁵C modification, which consequently interacts with DDB1 to facilitate PGC-1α transcription in lung cancer cells. Silencing circERI3 led to elevated ROS levels, a decrease in mitochondrial number and overall mitochondrial dysfunction. These detrimental effects were reversed by PGC-1α, which ultimately boosted mitochondrial energy metabolism[198]. In lung cancer, NSUN2 mediates m⁵C methylation of circRREB1, which is recognized by the reader protein ALYREF to facilitate its nuclear export. The exported circRREB1 subsequently stabilizes HSPA8 protein by inhibiting its ubiquitination. This stabilization in turn upregulates the PINK1/Parkin pathway and enhances mitophagy to promote tumor progression[199]. YTHDF2 drives malignant transformation of pre-B cells and induces aggressive B-ALL in vivo. Mechanistically, YTHDF2 recruits PABPC1 to recognize and stabilize F-type ATP synthase subunits in an m⁵C-dependent manner. This process enhances mitochondrial OXPHOS[200]. Mitochondrial morphology is closely associated with bioenergetics. PCIF1 was found to regulate lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) levels within mitochondria via LPP3, thereby inhibiting mitochondrial fission and inducing elongation. This remodeling significantly augments mitochondrial respiration, ultimately driving RCC progression[201]. METTL1 and its cofactor WDR4 form an m⁷G methylation complex that modifies tRNA substrates and enhances tRNA expression. Beyond tRNA regulation, the METTL1/WDR4 complex also promotes mitochondrial OXPHOS in GC cells by increasing SDHAF4 expression in Electron Transport Chain (ETC) Complex II through m⁷G modification[202]. TRMT61A can up-regulate the expressions of p-PI3K, CPT1A and CPT1B in prostate cancer through m¹A modification, promote lipidβ-oxidation in mitochondria to enhance mitochondrial metabolism[203].

7. The Interplay between RNA Methylation and the Tumor Microenvironment

7.1 Hypoxia-driven RNA methylations in metabolic reprogramming

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment acts not as a mere barrier but as an active orchestrator of cancer progression, driving profound adaptive shifts in cellular behavior[204]. A cornerstone of this adaptation is metabolic reprogramming, exemplified by the Warburg effect, which sustains energy and biomass production under hypoxia[205]. Under hypoxic conditions in GC, HIF-1α transcriptionally induces lncRNA-CBSLR, which subsequently serves as a molecular scaffold to recruit the m⁶A reader YTHDF2 and facilitate its binding to CBS mRNA, leading to downregulation of CBS protein. The reduction in CBS impairs the methylation of ACSL4, thereby targeting ACSL4 for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. As ACSL4 is a key promoter of ferroptosis, its degradation ultimately suppresses ferroptotic cell death[176]. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment (TME) in ccRCC instigates profound metabolic rewiring via RNA methylation. Central to this pathway is the sustained activation of HIF2α, which transcriptionally upregulates METTL3. Consequently, METTL3-dependent m⁶A methylation stabilizes TCF7L2 mRNA, elevating its protein expression. TCF7L2, in turn, functions as a metabolic switch to activate Wnt signaling and trigger de novo fatty acid synthesis. This hypoxia-driven metabolic shift enhances acetyl-CoA production, which facilitates histone acetylation and EMT, thereby providing pivotal support for tumor cell survival and dissemination under these adverse conditions[134]. Hypoxia triggers a feed-forward circuit in pancreatic cancer where the m⁶A demethylase ALKBH5, through demethylating HDAC4 mRNA, enables HDAC4-mediated stabilization of HIF1α. The activated HIF1α then further elevates ALKBH5 transcription, ultimately establishing a self-reinforcing ALKBH5-HDAC4-HIF1α loop that drives persistent glycolytic reprogramming[206]. In bladder cancer, HIF-1α directly transactivates the m⁶A reader ALYREF under hypoxic conditions. Upregulated ALYREF in turn binds to and stabilizes the mRNA of PKM2, leading to its augmented expression. This HIF-1α/ALYREF/PKM2 axis thereby accelerates glycolytic flux, fulfilling the bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands for bladder tumorigenesis.

7.2 RNA methylation in immune cell infiltration and function

Beyond its intrinsic role in hypoxic tumor microenvironment, RNA methylation exerts a profound 'inside-out' effect on the TME by modulating the expression of immunoregulatory molecules. In PDAC, elevated matrix stiffness stabilizes IGF2BP2 by reducing its ubiquitination. Stabilized IGF2BP2 then binds to m⁶A sites on SGMS2 mRNA, promoting its expression and enhancing sphingomyelin synthesis. This increase subsequently facilitates immune escape by promoting the localization of PD-L1 onto membrane lipid rafts, ultimately blunting tumor cell susceptibility to T cell-mediated killing[207]. In various tumor cells, YTHDF2 has been found to regulate immune escape. Mechanistically, the YTHDF2 deficiency significantly increases the m⁶A level in the 3'UTR region of CX3CL1, thereby promoting its expression. This upregulation, in the presence of Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), facilitates the polarization of anti-tumor macrophages. Additionally, YTHDF2 deficiency suppresses tumor glycolysis, which enhances mitochondrial respiration in CD8+T cells and subsequently stimulates their anti-tumor function. As a key effector cytokine produced by CD8+T cells, IFN-γ can downregulate YTHDF2 expression in tumor cells, thereby inhibiting tumor development at its source[208]. Specific ablation of USP47 in Treg cells augments anti-tumor immunity and disrupts Treg homeostasis. Mechanistically, USP47 stabilizes the m⁶A reader YTHDF1 via its deubiquitinase activity. Stabilized YTHDF1 then binds to m⁶A-modified c-Myc mRNA and promotes its decay, thereby repressing c-Myc protein synthesis and its-driven glycolytic flux, which ultimately attenuates the anti-tumor T cell immune response[209]. The m⁶A reader YTHDF1 exerts its function by post-transcriptionally stabilizing MCT1 mRNA in an m⁶A-dependent manner, leading to the augmentation of MCT1 expression. The upregulation of MCT1, a key lactate transporter, exacerbates glycolytic metabolism and lactate accumulation within the tumor microenvironment. This metabolic reprogramming creates an immunosuppressive niche by simultaneously dampening the cytotoxic activity of infiltrating CD8+T cells and stimulating the surface expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells, thereby enabling the cancer cells to escape immune surveillance[210]. CRC cells, when co-cultured with macrophages, reprogram macrophage metabolism by enhancing fatty acid oxidation (FAO). This metabolic shift is facilitated by the demethylase ALKBH5, which, through the removal of m⁶A modifications, upregulates the expression of CPT1A-a key rate-limiting enzyme in FAO. The ALKBH5-mediated upregulation of CPT1A consequently drives fatty acid metabolic reprogramming and promotes M2 macrophage polarization, ultimately fostering CRC progression[211]. By directly binding to and stabilizing MCT4 mRNA in an m⁶A-dependent manner, hnRNPA2B1 upregulates MCT4 expression. This enhances lactate efflux from tumor cells, thereby acidifying the tumor microenvironment, which subsequently suppresses immune cell cytotoxicity and fosters tumor immune escape[212]. In GBC, IGF2BP2 upregulates PRMT5 by enhancing its m⁶A modification. The increased PRMT5 activates SREBP1, thereby upregulating fatty acid synthases (e.g., ACC1, FASN, SCD1), driving lipid biosynthesis and accumulation. This metabolic alteration subsequently remodels the tumor immune microenvironment, resulting in expanded populations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Tregs and diminished CD8+ T cell infiltration, which together facilitate immune escape[213].

Within the TME, elevated cholesterol drives CD8+T cells to excessively take up fatty acids, which in turn induces lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. This chain of events severely compromises the cytotoxic function of CD8+T cells, thereby promoting immune escape. In HCC, the overexpression of NSUN2 in cancer cells augments this process. NSUN2 mediates m⁵C methylation to stabilize SOAT2 mRNA and enhance its transcription, leading to increased intracellular cholesterol levels that contribute to the suppression of CD8+T cell function[145]. In PDAC, the m⁵C reader ALYREF binds to m⁵C-modified JunD transcripts, enhancing their stability. This post-transcriptional regulation leads to an accumulation of JunD protein, which subsequently upregulates the expression of SLC7A5. When overexpressed on the surface of tumor cells, SLC7A5 competitively depletes essential amino acids from the TME. This nutrient deprivation impairs the infiltration and function of CD8+ T cells, thereby facilitating immune evasion[166]. In ccRCC, the loss of NSUN2 abrogates ENO1 mRNA stability via m⁵C modification, thereby suppressing the glycolytic-lactate pathway and subsequent histone H3K18 lactylation. This epigenetic change inhibits the TOM121/MYC/PD-L1 axis, leading to reduced PD-L1 expression and a consequent enhancement of CD8+ T cell-mediated tumor killing[109].