Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(3):1247-1265. doi:10.7150/ijbs.125930 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Targeting CDC42 Protects Mitochondrial Function through KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 Signaling in Acute Kidney Injury

1. Medical Examination Centre of the First Affiliated Hospital and CNTTI of College of Pharmacy, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China.

2. Basic Medicine Research and Innovation Center for Novel Target and Therapeutic Intervention (CNTTI), Ministry of Education, Chongqing 400016, China.

3. Department of Chemical Biology, College of Pharmacy, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China.

4. Sci-Tech Innovation Center, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing 400016, China.

5. Department of Anesthesia of the Second Affiliated Hospital, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, 400061, China.

Received 2025-9-27; Accepted 2025-12-9; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a severe clinical syndrome strongly associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, yet effective therapies remain elusive. Here, we identify cell division cycle 42 (CDC42) as a critical mediator of AKI. Analysis of human single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset revealed marked upregulation of CDC42 in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs), which was validated in murine models of cisplatin- and ischemia-reperfusion-induced AKI. Pharmacological inhibition, conditional knockdown, or genetic ablation of CDC42 significantly alleviated renal injury, preserved mitochondrial function, and reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) both in vivo and in vitro. Mechanistically, transcriptomic analysis, bioinformatic analysis, dual-luciferase reporter assays, ChIP assays and cellular functional validation revealed that CDC42 suppression activated a KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 transcriptional cascade, thereby promoting mitophagy and restoring mitochondrial homeostasis. Functional assays supported that this pathway plays a pivotal role in protecting RTECs from oxidative damage. Collectively, these findings uncover a previously unrecognized role of CDC42 in AKI pathogenesis and highlight CDC42 inhibition as a promising therapeutic strategy for mitigating mitochondrial damage and improving renal outcomes.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, cell division cycle 42, mitochondrial dysfunction, kruppel-like factor 2, hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, oxidative stress

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI), characterized by rapid deterioration of renal dysfunction, poses a critical healthcare challenge due to its high morbidity, persistently elevated mortality over decades, and substantial socioeconomic burden (1-3). Affecting 10-15% of hospitalized patients and over 50% of ICU admissions, AKI is strongly associated with adverse short-term outcomes, including a 5.6-fold higher 28-day mortality (4), and long-term risks of chronic kidney disease and mortality (5). Current management is largely limited to supportive care, highlighting the urgent need to explore novel prophylactic and therapeutic strategies.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are central drivers of AKI pathogenesis, particularly in renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs), which are highly metabolically active and rely on mitochondrial integrity to sustain reabsorption and energy production (6-9). Under AKI-related stress, mitochondria become dysfunctional and generate excessive levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are estimated to contribute up to 90% of cellular ROS production (6,7,10). The resulting cellular ROS surge exacerbates mitochondrial damage and RTECs injury (1,8), creating a self-perpetuating cycle of oxidative damage and organ dysfunction. Therefore, strategy break this vicious cycle and restore mitochondrial homeostasis represent promising therapeutic avenues. However, the molecular mechanisms regulating redox-sensitive mitochondrial maintenance in RTECs remain incompletely understood.

In our ongoing effort to explore the new therapeutic strategies for kidney diseases (11-13), integrated analysis of published human single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data highlighted a potential role of cell division cycle 42 (CDC42). CDC42 is a key regulator of actin cytoskeleton dynamics, controlling essential cellular processes such as shape, migration, cell cycle progression and vesicle trafficking (14-16). Moreover, CDC42 functions as a cellular signaling switch, modulating multiple signaling pathways and governing diverse cellular functions (17). Its broad biological functions make it essential for renal development (18) and an attractive therapeutic target in several malignancies, including gastric (19), colorectal (20), and breast cancers (21,22). While CDC42 has been reported to be involved in mitochondrial fission (23), its role in mitochondrial homeostasis, particularly in redox balance during AKI, remains unknown.

Here, we report for the first time that CDC42 inhibition activates KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 signaling axis to promote mitophagy, restore mitochondrial function, and attenuate AKI by reducing oxidative stress. Using murine models of cisplatin- and ischemic-reperfusion (I/R)-induced AKI, as well as cisplatin-caused injury in human RTECs, we show that pharmacological and genetic suppression of CDC42 significantly attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction and renal injury. Collectively, these findings identify CDC42 as a previously unrecognized regulator of redox-sensitive mitochondrial homeostasis and offers mechanistic insights into its therapeutic potential in AKI.

Methods

Study approval

All animal experiments in this study were approved by the Animal Research and Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University (IACUC-CQMU-2023-11016) following the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals

Male mice (C57BL/6J, 8-weeks old) were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Cdc42flox/- and Cdh16-Cre mice, both with a C57BL/6 background, were purchased from the Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc. (Shanghai, China). Cdc42flox/- mice were crossed with Cdh16-Cre mice using the Cre-loxP system to generate renal tubular epithelial-specific Cdc42 knockdown mice Cdc42+/-; Cdh16-Cre (Cdc42Cdh16 KD), and Cdc42flox/flox mice (Cdc42f/f) were generated by mating Cdc42flox/- mice with Cdc42flox/- mice. The genotypes of mice were identified by PCR analysis of the DNA of tail tissues with the primer sequences presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility under controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and humidity (55 ± 10%), with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and ad libitum access to autoclaved water and food. After a one-week acclimatization, mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups as detailed in Figures 1, 2, and 3. All experimental treatments were performed at consistent times of the day to minimize circadian influences on renal function.

Measurement of blood levels of creatinine and urea

The blood levels of creatinine and urea in mice were measured using a high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) as previously described (11).

Plasmids, lentivirus short-hairpin RNA construction, and cell transfection

The stable knockout (KO) cell line was constructed using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. LentiCRISPRv2-sgRNA-CDC42 (Sense 5'-CACCGACAGTCGGTACATATTCCGA-3' and anti-sense 5'-AAACTCGGAATATGTACCGACTGTC-3'), lentiCRISPRv2-sgRNA-KLF2 (sense 5'-CACCGCGCGTCGTCGAAGAGACCGA-3' and anti-sense 5'-AAACTCGGTCTCTTCGACGACGCGC-3'), lentiCRISPRv2-sgRNA-HIF-1α (sense 5'-CACCGAGATGCGAACTCACATTATG-3' and anti-sense 5'-AAACCATAATGTGAGTTCGCATCTC-3'), lentiCRISPRv2-sgRNA-PINK1 (sense 5'-CACCGCGTGGACCATCTGGTTCAAC-3' and anti-sense 5'-AAACGTTGAACCAGATGGTCCACGC-3'), and the lentiCRISPRv2-sgRNA-NC were purchased from Bio-rabbit (China, Shanghai). Lentivirus was packaged in HEK293T cells with Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, #L3000008) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h of infection, the supernatant of HEK293T cells was collected and used to infect HK-2 cells in the presence of polybrene (Beyotime; #C0351) to assist transfection. Transfected cells were then selected with puromycin (Beyotime; #ST551) to generate stable knockout cell lines. The knockout efficiency was evaluated by western blot (WB) analysis.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

RNA sequencing was performed by Sangon Biotech (China, Shanghai) following total RNA extraction from HK-2 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, #15596018CN). For samples without biological replicates, read count data were normalized using the TMM method, followed by an analysis of variance analysis with DEGseq. For samples with biological replicates, differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq. Significantly different genes were identified based on adjusted p value ≤ 0.05 and absolute log2 fold change (| log2FC |) ≥ 1.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and figures were generated with GraphPad Prism version 9 (La Jolla, CA). Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Anderson-Darling, D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus, or Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between two groups were analyzed using an independent-sample t-test, while One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey′s or Games-Howell post-hoc comparison, was used for multiple group comparisons. * p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01, ***0.0001 < p ≤ 0.001 and **** p ≤ 0.0001 were considered significant difference.

Additional experimental details are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Human scRNA-seq data analysis identified CDC42 as a pivotal gene in AKI pathogenesis

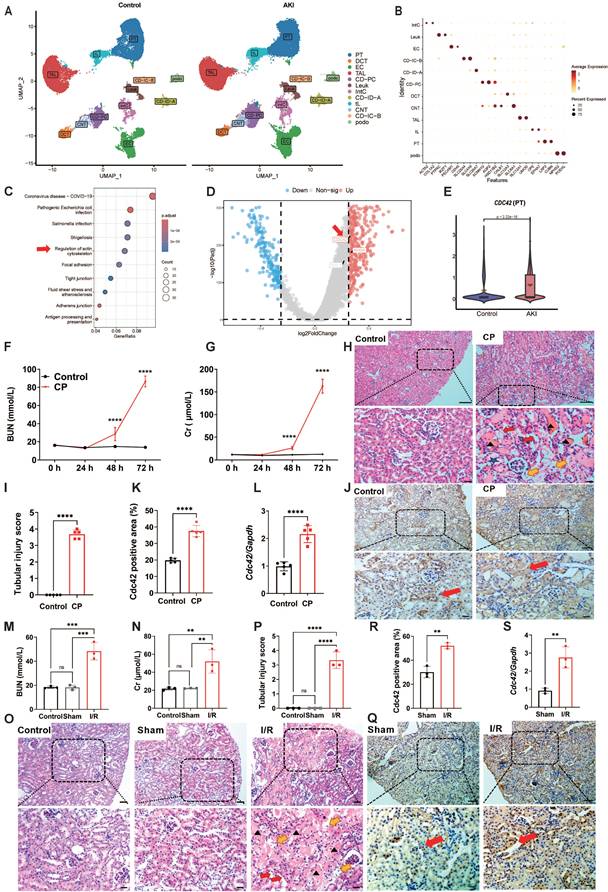

To explore the potential pathogenic mechanisms of AKI, we first downloaded raw data of human AKI from published scRNA-seq databases (24). After performing dimensionality reduction and clustering analysis (Figure 1A), and annotating cell types based on canonical markers (Figure 1B), we identified 12 major clusters from 96527 cells between control and AKI groups. Renal proximal tubule (PT) cells have become a major target for exploring AKI in recent years due to their abundance and heightened susceptibility/responsiveness to external insults (25,26). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of PT cells from control and AKI groups revealed that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were significantly enriched not only in infection-related pathways that associated with mortality etiology in AKI patients, but also significantly in actin cytoskeleton signaling pathways, which particularly captured our attention (Figure 1C).

The actin cytoskeleton, one of the most critical intracellular scaffold structures, maintains cell morphology, motility, and division through diverse actin isoforms and regulatory proteins governed by intricate signaling networks (27,28). Researches have demonstrated its involvement in mitochondrial homeostasis regulation (29). Its assembly/disassembly is primarily regulated by the Rho GTPases family, consisting of RHOA, RAC1, and CDC42, which coordinates different cellular processes through downstream effectors (30). Further volcano analysis in PT cells of control and AKI groups revealed that CDC42 is the most significantly altered gene in Rho GTPases family (Figure 1D). Violin plot also showed that CDC42 expression was significantly upregulated in PT cells of the AKI group (Figure 1E). Taken together, the scRNA-seq data analysis of human AKI suggested CDC42 may be a pivotal gene involved in the pathogenesis of AKI.

CDC42 was upregulated in cisplatin (CP)- and ischemia-reperfusion (I/R)-induced AKI mouse models

To further define the role of CDC42 in AKI, we adopted two most recognized and widely used murine models of CP- and I/R-induced AKI (31). In CP-induced AKI mice, blood urea nitrogen (BUN, Figure 1F) and creatinine (Cr, Figure 1G) were progressively increased and climaxed at 72 h post-exposure. Histologic analysis of kidney sections from the AKI mice (72 h post CP exposure) revealed severe tubular injury, as evidenced by hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining (Figure 1H and 1I). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis showed that Cdc42 was abundantly expressed in mice kidney tissues, particularly in the renal tubular epithelial cells (RTECs) (including both PT cells and distal convoluted tubule (DCT) cells) (Figure 1J), which was consistent with the human AKI scRNA-seq results (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure S1). Moreover, both IHC (Figure 1K) and q-PCR (Figure 1L) analyses indicated a significant upregulation of Cdc42 in the kidneys of CP-AKI mice. In I/R-induced AKI mice, renal injury was evidenced by significantly elevated BUN and blood Cr levels, and severe tubular damage (Figure 1M-1P). In addition, no significant difference in BUN, Cr, or tubular injury scores were observed between the control and the sham groups, suggested that surgical stress did not affect renal function. Similarly, IHC staining and q-PCR analyses revealed a significantly increased Cdc42 expression in the RTECs of I/R-AKI mice when compared with the sham controls (Figure 1Q-1S).

CDC42 was upregulated in the kidneys of AKI patients, CP-AKI mice and I/R-AKI mice. (A) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of 96527 cells from individuals with controls (left) and AKI (right). Data were originated from the scRNA-seq dataset reported by Christian et al. (24). (Podo, podocytes; PT, proximal tubule; tL, thin limb; TAL, thick ascending limb; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; CNT, connecting tubule; CD-PC/IC-A/IC-B, collecting duct principal/intercalated cells type A and B; Leuk, leukocytes; IntC, interstitial cells); (B) Dot plot showing the representative maker genes of each cell cluster; (C) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of PT cells from control and AKI group; (D) Volcano plot of PT cells in the control and AKI group; (E) Violin plot indicated significantly upregulation of CDC42 in PT cells from AKI group; (F) BUN and blood Cr (G) concentrations in mice were increased upon CP-challenge time-dependently (n = 5, means ± SEM); (H) Representative H&E-stained kidney sections from CP-treated mice showed tubular injury features such as cast formation (black arrows), brush border loss (red arrows), epithelial cell necrosis (yellow arrows), and tubular dilation (blue pentagram). n = 5, scale bars: 100 μm (overview), 20 μm (magnified); (I) Renal tubular injury scores of (H); (J-K) Immunohistochemical staining revealed elevated Cdc42 expression (brown signal, red arrows) in renal tubules of CP-AKI mice (n = 5). Scale bars: 50 μm (overview), 20 μm (magnified); (L) Renal Cdc42 mRNA levels were significantly increased in CP-induced AKI mice (n = 5); (M) BUN and Cr (N) concentrations were increased in I/R-induced AKI mice (n = 3); (O) H&E staining demonstrated severe kidney injury in I/R mice (n = 3). Scale bars: 50 μm (overview), 20 μm (magnified); (P) Renal tubular injury scores of (O); (Q-R) IHC staining implied increased Cdc42 expression in I/R-AKI mice (n = 3). Scale bars: 50 μm (overview), 20 μm (magnified); (S) Renal Cdc42 mRNA levels were increased in I/R-AKI mice (n = 3); Data were presented as means ± SD unless other noted. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

Cdc42 inhibition protected against kidney injury in CP-induced AKI mice

To investigate the therapeutic potential of Cdc42 inhibition in AKI, we administered ZCL278, a Cdc42-selective inhibitor, to AKI mice (32). In CP-induced AKI mouse model, two treatment regimens were designed: 1) post-treatment (CP+ZCL) to evaluate therapeutic efficacy, and 2) combined pre- and post-treatment (ZCL+CP+ZCL) to assess preventive and therapeutic efficacy. Notably, ZCL278 treatment effectively reduced renal Cdc42 protein expression (Figure 2A) and active GTP-Cdc42 levels (Figure 2B), significantly lowering elevated BUN and blood Cr concentrations in CP-AKI mice (Figure 2C and 2D). Importantly, ZCL278 showed no nephrotoxicity in healthy mice, as evidenced by stable BUN and Cr levels (Figure 2C and 2D). Furthermore, ZCL278 treatment prolonged the survival time of CP-induced AKI mice, with a median survival time of 108 hours in the CP group and 132 hours in the CP+ZCL group, indicating that ZCL278 has a sustained protective effect (Figure 2E). Meanwhile, H&E and TUNEL staining analyses (Supplementary Figure S2A-S2D), protein levels of Bax (a pro-apoptotic regulator) and Bcl-2 (an anti-apoptotic regulator) (Figure 2F), mRNA expression of kidney-injury-molecule-1 (Kim-1) and inflammatory cytokines (Il-1β, Il-6, and Tnf-α) (Figure 2G-2H) indicated that ZCL278 greatly attenuated kidney injury in CP-induced AKI mice. Given the concordance between mitochondrial (Supplementary Figure S3) and whole-cell (Figure 2F) Bax expression under CP challenge with or without ZCL278 treatment, subsequent studies used whole-cell Bax expression as an apoptotic marker.

Cdc42 inhibition alleviated mitochondrial dysfunction in CP-AKI mice

Cellular oxidative stress, induced by ROS released from mitochondrial dysfunction, is the central pathological mechanism in AKI (6,7,10). Given the crosstalk between actin cytoskeleton dynamics and mitochondrial function (29), we hypothesize that Cdc42 inhibition may protect against AKI by modulating mitochondrial function. Isolation of mitochondria from mouse kidneys (Figure 2I-2J) revealed that Cdc42 was increased in CP-AKI mouse kidney mitochondria, which indicating its involvement in AKI mitochondrial regulation. Mitochondria homeostasis relies on a dynamic balance among PGC-1α/NFR2-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis, MFN2/DRP1-mediated mitochondrial fusion and fission, and PINK1/PARKIN-mediated mitophagy (9), with impairment of any of these processes causing mitochondrial dysfunction. Notably, ZCL278 treatment effectively maintained mitochondrial homeostasis in CP-induced AKI mice (Figure 2K-2M). To further assess mitochondrial function, we characterized mitochondrial ultrastructure in CP-AKI mice with or without ZCL278 treatment. As illustrated in Figure 2N and 2O, Cdc42 inhibition with ZCL278 treatment significantly improved CP exposure-caused mitochondrial ultrastructural abnormalities. In addition, ZCL278-mediated Cdc42 inhibition rescued the compromised ATP generation (Figure 2P) in CP-challenged mice.

Taken together, pharmacological inhibition of Cdc42 via ZCL278 treatment restored mitochondrial function in CP-induced kidney injury. Both administration routes of ZCL278 provided protective effects, with combined pre- and post-treatment showing superior efficacy.

Cdc42 inhibition protected against kidney injury and mitochondrial dysfunction in I/R-induced AKI

To comprehensively evaluate the reno-protective effects of Cdc42 inhibition across etiologically distinct AKI models, we assessed renal injury and mitochondrial function in I/R-AKI mice following ZCL278 treatment. Consistent with results in CP-AKI mice, ZCL278 reversed I/R-induced increase in Cdc42 protein expression and its activation levels (Figure 2Q-2R), reduced elevated BUN and blood Cr concentrations (Figure 2S and 2T), and alleviated renal tubular injury (Supplementary Figure S2E and S2F). Additionally, ZCL278 treatment effectively preserved mitochondrial function (Figure 2U-2W).

Given the comparable efficacy in both CP- and I/R-AKI mouse models, combined with the higher clinical relevance of nephrotoxic AKI and the mouse mortality associated with I/R surgery, we primarily conducted subsequent animal experiments in CP-induced AKI model.

Cdc42 inhibition by ZCL278 attenuated renal injury and mitochondrial dysfunction in AKI mice. (A-B) ZCL278 treatment inhibited the elevated renal Cdc42 protein expression (A) and GTP-Cdc42 levels (B) in CP-induced AKI mice (n = 6); (C-D) ZCL278 attenuated CP-induced increase in BUN (C) and Cr levels (D) (n = 5 in control+ZCL278 group, n = 7~9 in other groups, means ± SEM); (E) ZCL278 improved survival in CP-challenged mice; (F) ZCL278 reversed CP-induced changes in the renal protein expression of apoptotic indicator Bax and the antiapoptotic indicator Bcl-2 (n = 6); (G, H) ZCL278 reversed CP-induced increases in renal mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory Il-1β, Il-6 and Tnf-α (G) and Kim-1 (H) (n = 7~9); (I) Mitochondria were isolated from mouse kidneys (n = 3); (J) Mitochondria Cdc42 expression was upregulated in CP-AKI mice (n = 3); (K-M) ZCL278 enhanced CP-induced increase in renal protein expression of mitophagy-related indicators Parkin and Pink1 (K), and counteracted CP-induced changes in mitochondrial fission-related indicator Drp1, mitochondrial fusion-related indicator Mfn2 (L), and mitochondrial biogenesis related indicators Pgc-1α and Nrf2 (M) (n = 6); (N) Representative TEM imaging revealed that ZCL278 alleviated mitochondrial ultrastructural damage in CP-induced AKI RTECs (red arrows: mitochondria, yellow arrows: brush border, scale bar = 1 μm, n = 3); (O) Quantification of the mitochondrial aspect ratio; (P) ZCL278 restored renal ATP levels in CP-AKI mice (n = 7~9); (Q-R) ZCL278 inhibited the upregulation of Cdc42 and GTP-Cdc42 protein levels in I/R-induced AKI mice (n = 3 in control and sham groups, n=6 in I/R and ZCL+I/R+ZCL group); (S-T) ZCL278 attenuated I/R-induced elevation in BUN (S) and Cr levels (T) (n = 3 in control and sham groups, n=6 in I/R group, and n=10 in ZCL+I/R+ZCL group); (U-W) ZCL278 enhanced I/R-induced increase in renal protein expression of Parkin and Pink1 (U), and reversed I/R-induced changes in Drp1 and Mfn2 (V), as well as Pgc-1α and Nrf2 (W) (n = 3); Data were presented as means ± SD unless other noted. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

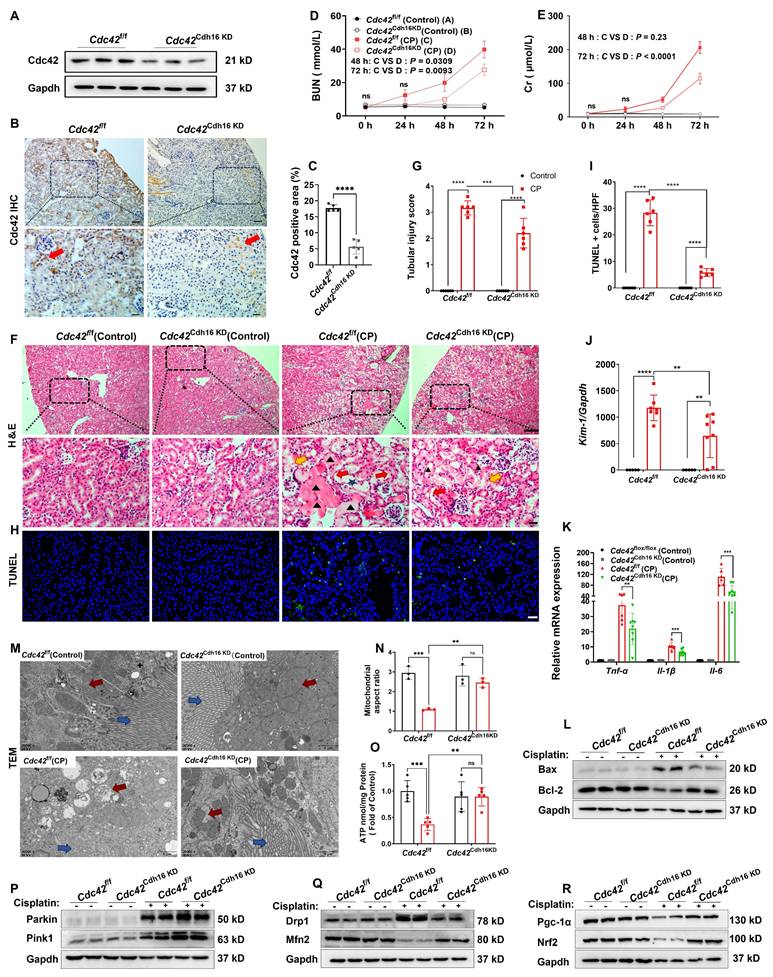

Conditional knockdown of Cdc42 in RTECs alleviated kidney injury and restored mitochondrial function in AKI mice. (A) The knockdown effect of Cdc42 was verified by WB; (B-C) IHC staining showed reduced Cdc42 expression in RTECs of Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice; (D-E) BUN (D) and blood Cr levels (E) were lower in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice than those of Cdc42f/f mice after CP administration (n = 8~10 in CP group, n = 5 in control group, means ± SEM); (F) H&E staining revealed milder renal damage in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice post-CP (scale bars: 100 μm, overview; scale bars: 20 μm, magnified; n = 5~6); (G) Analysis of renal tubular injury scores; (H)Representative images and quantification (I) of TUNEL staining in mouse kidney sections showed decreased apoptotic cells in Cdc42 cKD mice after CP challenge (Green staining and blue staining indicated TUNEL-positive cells and nuclei, respectively; n = 5~6, scale bar = 20 μm); (J-K) mRNA expression of Kim-1 (J) and pro-inflammatory factors (K) in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice was significantly lower than that in Cdc42f/f mice when challenged with CP (n = 5~8); (L) Bax and Bcl-2 protein expression were reversed by Cdc42Cdh16 KD upon CP exposure (n = 5~6); (M) Representative transmission electron micrographs of mitochondria from mice RTECs indicated improved mitochondrial ultrastructure in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice after CP exposure (red arrows: mitochondria, blue arrows: brush border; n = 3); (N) Mitochondrial aspect ratio quantification; (O) Cdc42 cKD attenuated the decline in renal ATP levels of AKI mice (n = 5); (P-R) Protein expression of mitochondrial homeostasis related indicators showed Cdc42 cKD improved mitochondrial homeostasis in AKI mice (n = 5~6). Data were presented as means ± SD unless other noted. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

Conditional knockdown of Cdc42 in RTECs alleviated kidney injury and mitochondrial dysfunction in CP-induced AKI mice

To establish an appropriate renal conditional Cdc42 knockdown (cKD) mouse model to mimic CP-induced kidney injury, we first analyzed publicly available scRNA-seq data from control and CP-AKI mice (33) (Supplementary Figure S4A-S4B). The results revealed that the Nagl (a marker of AKI) (34,35) (Supplementary Figure S4C-S4E) and Cdc42 (Supplementary Figure S4F-S4H) expression in both PT and DCT cells were significantly increased in CP-AKI mice, with DCT cells showing injury severity similar to or greater than that of PT cells. CP exposure is known to impair glomerular filtration rate (GFR) primarily by damaging the distal nephron including DCT, connecting tubule and collecting ducts, and the S3 segment of the PT (36,37). This understanding is supported by previous studies (38,39) and our H&E staining (Figure 1H), which demonstrate that CP causes damage to both PT and DCT cells in AKI mice. Based on these findings, we selected Cdh16-Cre mice to generate a RTEC-specific Cdc42 conditional knockdown mouse model using the Cre-LoxP system, enabling targeted investigation of Cdc42 function in CP-AKI. The knockdown efficiency was verified by identification of mice genotyping (Supplementary Figure S5), WB assay (Figure 3A) and IHC staining (Figure 3B-3C).

Consistent with the nephro-protective profile of ZCL278 treatments, Cdc42 cKD in mice RTECs attenuated CP-induced increases in BUN and Cr levels (Figure 3D-3E), ameliorated histopathological damage (Figure 3F-3G), and decreased renal apoptotic cells in CP-AKI mice (Figure 3H-3I). Furthermore, inflammatory and apoptotic markers further supported these findings, as Cdc42 cKD mice exhibited lower Bax, Kim-1, Il-6, Tnf-α, and Il-1β, alongside higher Blc-2 expression (Figure 3J-3L). Further analyses revealed that Cdc42 cKD AKI mice exhibited improved mitochondrial morphology (Figure 3M-3N), significantly higher ATP levels (Figure 3O) and restored mitochondrial homeostasis (Figure 3P-3R).

Taken together, these results revealed that pharmacological and genetic blockade of Cdc42 improved mitochondrial dysfunction, contributing to its protection against AKI.

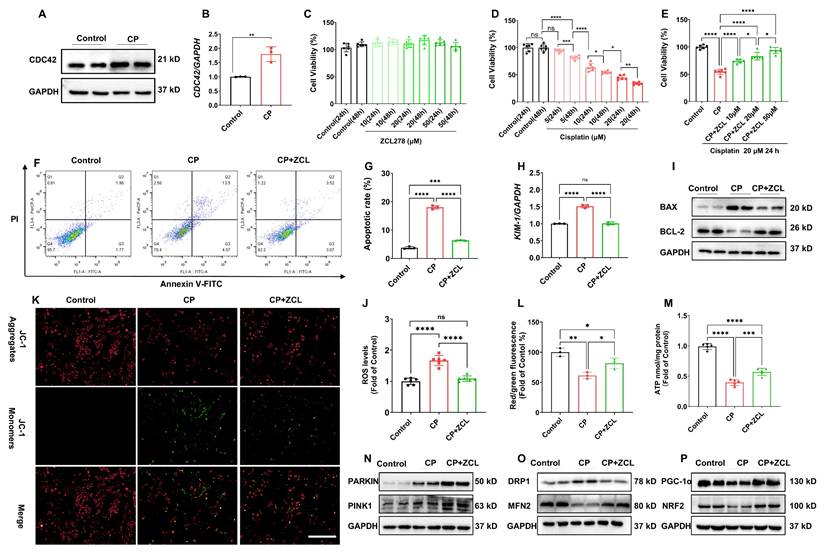

Inhibition of CDC42 suppressed CP-induced cell injury and improved mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro

We employed HK-2 cells, an immortalized RTEC as an in vitro model to investigate the direct role of CDC42 in AKI. In accordance with our in vivo findings, CDC42 mRNA and protein expression was significantly upregulated in CP-treated HK-2 cells compared with the controls (Figure 4A-4B). CCK-8 assays showed that ZCL278 treatment (up to 50 μM for 48 h) did not affect cell viability (Figure 4C), indicating its safety profile. As anticipated, CP exposure decreased cell viability concentration- and time-dependently (Figure 4D), with 20 μM CP for 24 h reducing viability to ~50% of control levels. These conditions were set for subsequent experiments to mimic AKI in vitro. Notably, ZCL278 restored CP-induced viability loss in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4E), accompanied by reduced apoptosis (Figure 4F-4G) and KIM-1 expression (Figure 4H). Additionally, ZCL278 treatment reversed CP-induced changes in BAX and BCL-2 protein levels (Figure 4I).

Given that mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary source of ROS in AKI (6,7,10), we assessed ROS levels and found that ZCL278 treatment significantly reduced CP-induced ROS accumulation (Figure 4J). Furthermore, ZCL278 treatment restored ATP synthesis and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) (Figure 4K-4M), while WB analyses of mitochondrial homeostasis markers further confirmed that CDC42 inhibition mitigated CP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction (Figure 4N-4P).

Genetical knockout of CDC42 protected HK-2 cells against CP-caused cell injury and mitochondrial dysfunction

To further validate the protective role of CDC42 inhibition in AKI, we constructed a stable CDC42 knockout (KO) HK-2 cell line (Figure 5A). WB analysis revealed that CDC42 KO reversed CP-induced changes in BAX and BCL-2 protein expression in the negative control (NC) cells (Figure 5B). Also, CDC42 KO alleviated the CP-induced decline in cell viability (Figure 5C) and CP-induced increase in cell apoptosis (Figure 5D-5E). Additionally, CDC42 KO markedly mitigated mitochondrial dysfunction and alleviated cellular oxidative stress, as evidenced by a marked reduction in CP-induced ROS accumulation (Figure 5F) and restoration of MMP and ATP levels (Figure 5G-5I).

Taken together, these above in vitro cellular studies showed that inhibition of CDC42 protected HK-2 cells from ROS-induced cellular oxidative stress injury by ameliorating mitochondrial dysfunction, which further supported CDC42 as a potential therapeutic target for AKI.

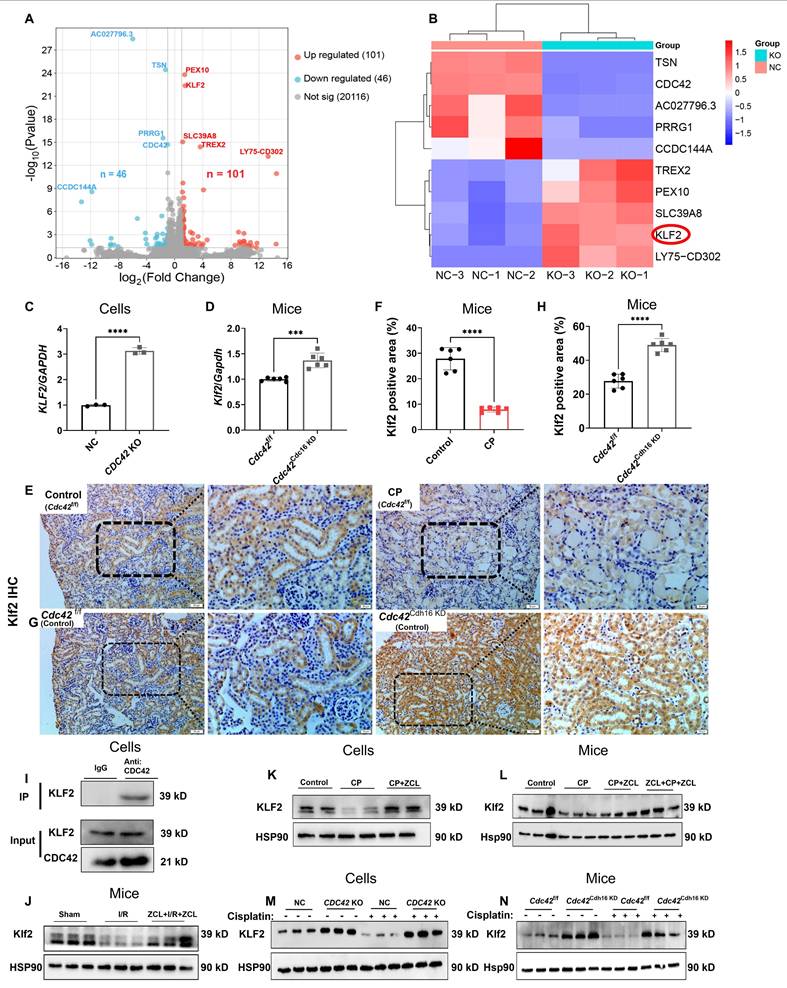

KLF2 was a downstream target gene of CDC42 in regulating AKI

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying CDC42-mediated renal protection in AKI, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on CDC42 KO cells and NC cells. A total of 147 DEGs were identified (Figure 6A), while heatmap analysis (Figure 6B) highlighted the top 10 most significantly altered genes, among which KLF2 emerging as a key candidate due to its well-established roles in mitochondrial function (40,41), oxidative stress-mediated cell damage and apoptosis (42). This hypothesis was then supported by q-PCR, showing that both CDC42 KO (in vitro) and cKD (in vivo) significantly increased KLF2 mRNA levels (Figure 6C-6D). Furthermore, IHC staining revealed abundant Klf2 expression in RTECs, which was decreased following CP exposure (Figure 6E-6F), but was restored in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice (Figure 6G-6H).

Critically, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays indicated the protein interaction between CDC42 and KLF2 (Figure 6I). Importantly, CDC42 inhibition reversed the CP- and I/R-induced reduction in KLF2 expression in both in vivo (Figure 6J, 6L, 6N) and in vitro (Figure 6K, 6M) models, consistent with IHC results. This regulation axis was also supported by the fact KLF2 KO failed to affect the CDC42 expression (Figure 7D).

ZCL278 treatment attenuated CP-induced cell injury and mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro. (A-B) The protein (A) and mRNA (B) levels of CDC42 were significantly increased in HK-2 cells upon CP exposure (n = 3); (C) ZCL278 at tested conditions had a negligible effect on cellular activity (n = 6); (D) CP exposure reduced HK-2 cells cell viability in a concentration- and dose-dependent manner (n = 6);(E) ZCL278 concentration-dependently ameliorated the CP-induced decline in cell viability (n = 6); (F) Representative images of apoptosis by flow cytometry showed ZCL278 reduced CP-induced cell apoptosis (n = 3); (G) Quantitative results of (F); (H) ZCL278 alleviated CP-induced upregulation of KIM-1mRNA (n = 3); (I) ZCL278 reversed CP-induced changes in protein expression of BAX and BCL-2 (n = 3); (J) ZCL278 reduced CP exposure-induced increase in cellular ROS accumulation (n = 3); (K-L) ZCL278 alleviated CP-induced decline in cellular MMP (n = 3); (M) ZCL278 mitigated the decline in ATP levels in CP-treated cells (n = 3); (N-P) ZCL278 reversed CP exposure-caused changes in protein expression of DRP1 and MFN2 (O), PGC-1α and NRF2 (P), and enhanced CP-caused increase in protein expression of PARKIN and PINK1 in HK-2 cells (N) (n = 3). Data were presented as means ± SD. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

Knockout of CDC42 in HK-2 cells protected against CP-induced cell injury and mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro. (A) CDC42 knockout effect in HK-2 cells was verified by WB; (B) CDC42 KO reversed CP-induced elevation of BAX and reduction of BCL-2 protein expression (n = 3); (C) CDC42 KO alleviated CP-induced decrease in cell viability (n = 6); (D-E) Flow cytometry analysis indicated that CDC42 KO reduced CP-induced cell apoptosis (n = 3); (F) CDC42 KO reduced cellular ROS accumulation upon CP exposure (n = 3); (G) CDC42 KO alleviated CP-induced decrease in cellular ATP levels (n = 3); (H-I) Representative images of the mitochondrial membrane potential (H) and the related quantitative analyses of JC-1 fluorescence intensity (I) demonstrated that CDC42 KO reversed the decrease in MMP after CP challenge (n = 3, scale bar = 200 μm). Data were presented as means ± SD. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

These findings identify KLF2 as a critical downstream target of CDC42 inhibition, providing novel insights into its protective role against AKI in mitochondria and oxidative stress.

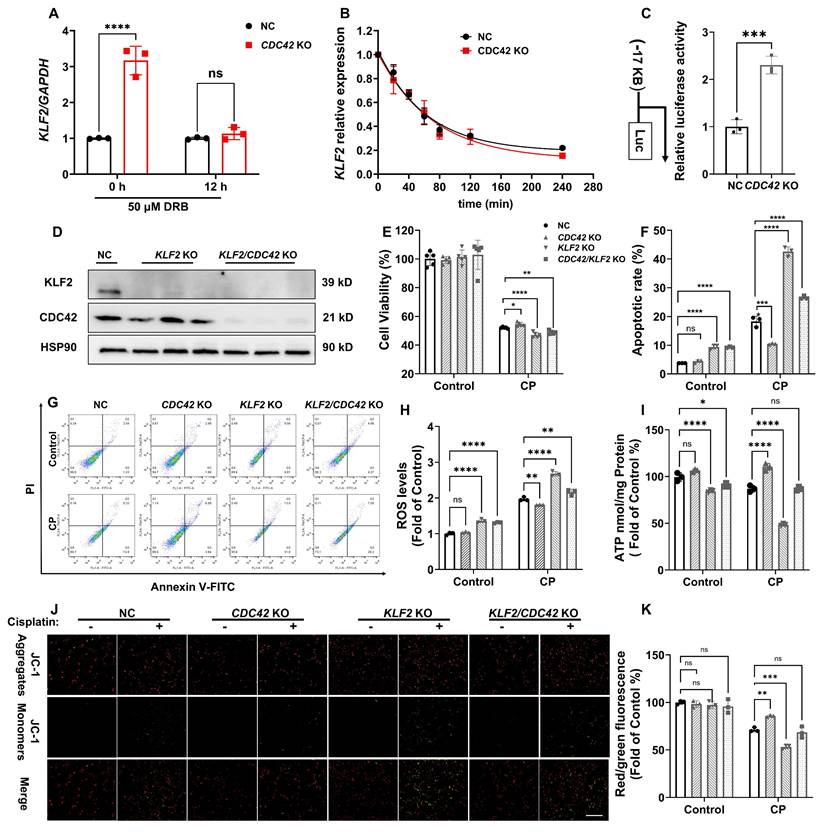

CDC42 KO increased KLF2 promoter activity and exerted its protective effect against kidney injury by mediating KLF2

To explore the mechanism underlying the regulation of KLF2 by CDC42, we examined KLF2 expression in the presence and absence of DRB (a potent RNA polymerase inhibitor). Notably, the increased KLF2 mRNA level caused by CDC42 KO was completely abolished by DRB treatment (50 μM) (Figure 7A), indicating that CDC42-mediated KLF2 regulation occurs at the transcriptional level. Considering the mature mRNA abundance is influenced by both transcription rate and degradation (43), we first assessed the half-life of KLF2 mRNA in HK-2 cells. We observed that CDC42 KO caused a slight increase in KLF2 mRNA stability (NC: t1/2 = 43.6 ± 7.8 min vs CDC42 KO: t1/2 = 50.2 ± 11.1 min, p = 0.38) (Figure 7B), demonstrating that CDC42-mediated KLF2 primarily through transcriptional activation rather than mRNA stability. Then, dual-luciferase assay revealed that CDC42 KO significantly increased the KLF2 promoter activity (1.7-kB KLF2- Luc) by 2.5-fold, indicating that CDC42 KO promotes KLF2 transcription to increase its mRNA expression (Figure 7C).

KLF2 was the downstream target of CDC42 in AKI. (A) Volcano plots of the detected genes between NC cells and CDC42 KO cells (n = 3); (B) Heatmap showed 10 DEGs with the most significant differences; (C) CDC42 KO increased the mRNA expression of KLF2 in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (D) Renal Klf2 mRNA expression was increased in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice compared to Cdc42f/f mice (n = 5); (E-F) Immunohistochemistry showed reduced expression of Klf2 in AKI mice (scale bars: 50 μm, overview; scale bars:20 μm, magnified; n = 6); (G-H) Immunohistochemistry revealed increased Klf2 expression in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice compared to Cdc42f/f mice (scale bars: 50 μm, overview; scale bars:20 μm, magnified; n = 5); (I) Co-IP assays confirmed the interaction between CDC42 and KLF2 in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (J) Decreased Klf2 protein expression in I/R-induced AKI mice was reversed by ZCL278 (n = 3 in sham group, n = 6 in other groups); (K) ZCL278 reversed CP-induced reduction of KLF2 protein expression in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (L) ZCL278 ameliorated CP-induced reduction in renal Klf2 protein in mice (n = 6); (M) CDC42 KO increased the protein expression of KLF2 in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (N) Renal Klf2 protein expression was upregulated in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice when compared to Cdc42f/f mice (n = 3). Data were presented as means ± SD. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

CDC42 KO protected CP-induced cell injury by enhancing KLF2 promoter activity. (A) mRNA induction of KLF2 by CDC42 KO was abrogated after 50 μM DRB treatment (n = 3); (B) mRNA stability showed that the mRNA half-life of KLF2 was similar in NC cells and CDC42 KO cells (n = 3); (C) The dual-luciferase assay revealed a significant increase in KLF2 promoter activity in CDC42 KO cells (n = 3); (D) The knockout effect of CDC42 and KLF2 in HK-2 cells was verified by WB; (E) The protection of CDC42 KO in cell viability was counteracted by KLF2 KO upon CP exposure (n = 5); (F-G) Representative images of apoptosis assay by flow cytometry (G) and the statistical analysis (F) indicated that KLF2 KO aggravated CP-induced cell apoptosis (n =3); (H) KLF2 KO in HK-2 cells significantly increased cellular ROS concentrations (n = 3); (I) KLF2 KO worsened the CP-induced decline in cellular ATP levels (n = 3); (J-K) Representative images of the mitochondrial membrane potential (J) and the quantitative analyses of JC-1 fluorescence intensity (red/green) (K) revealed that KLF2 KO further contributed to the decrease in MMP after CP exposure (n = 3, scale bar: 200 μm). Data were presented as means ± SD. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

To validate that CDC42 inhibition attenuates AKI via KLF2, we established KLF2 KO and KLF2/CDC42 double KO (dKO) cells (Figure 7D). Interestingly, KLF2 KO alone significantly aggravated the CP-induced decrease in cell viability and increase in cell apoptosis. Unexpectedly, the protective effects of CDC42 KO on CP-induced cell injury were virtually counteracted in CDC42/KLF2 dKO cells (Figure 7E-7G). Consistently, KLF2 KO exacerbated CP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, as evidenced by increased cellular ROS concentrations, and decreased ATP and MMP levels. Strikingly, the ability of CDC42 KO to restore mitochondrial function was nearly abolished in CDC42/KLF2 dKO cells (Figure 7H-7K).

Collectively, these results show CDC42 exerts its protective effects against AKI by transcriptionally upregulating KLF2.

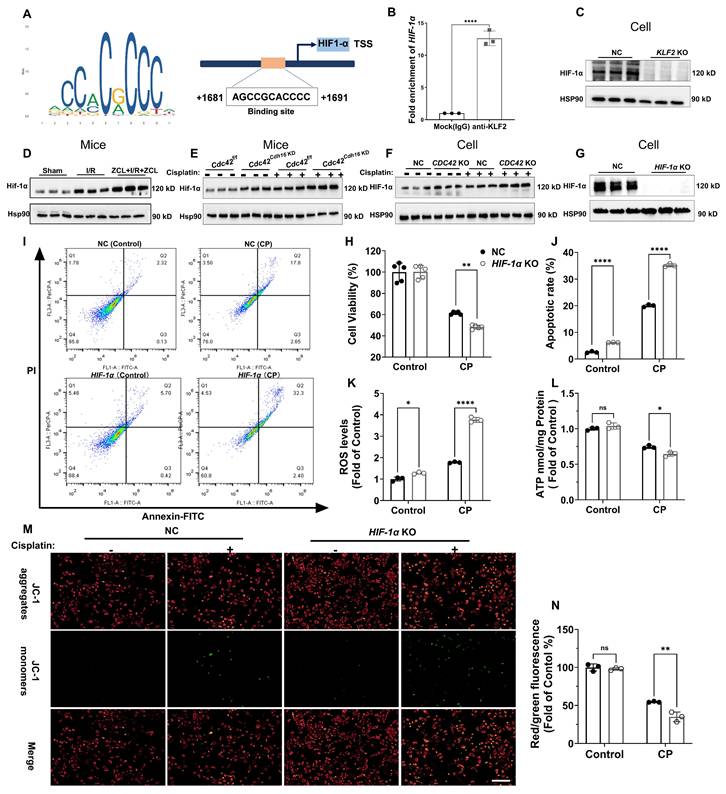

KLF2 regulated AKI mechanism through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α

To elucidate the mechanistic link between KLF2 and AKI, we performed a transcription factor database search using JASPAR, TRRUST, and KnockTF, identifying hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) as a key downstream target. HIF-1α encodes the alpha subunit of transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), a key regulator of cellular and systemic homeostatic responses to hypoxia (44). JASPAR database revealed conserved KLF2-binding motifs in the HIF-1α promoter (Figure 8A), which was experimentally validated by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) showing significant HIF-1α promoter enrichment in anti-KLF2 group (Figure 8B). Functionally, KLF2 KO reduced HIF-1α protein expression (Figure 8C), whereas CDC42 inhibition via ZCL278 or genetic approaches (KO/cKD) upregulated HIF-1α in both CP- and I/R-AKI models (Figure 8D-8F).

To define HIF-1α' role in AKI, we generated HIF-1α KO cells and their corresponding rescue model (HIF-1α KO + HIF-1α cells) (Figure 8G and Supplementary Figure S6). As expected, HIF-1α KO worsened CP-induced cellular damage (Figure 8H-8J) and mitochondrial dysfunction (ROS↑, ATP↓, MMP↓; Figure 8K-8N), whereas the aforementioned damage was reversed in HIF-1α KO + HIF-1α cells (Supplementary Figure S6). These data collectively show that CDC42 inhibition ameliorates AKI through KLF2-dependent transcriptional activation of HIF-1α.

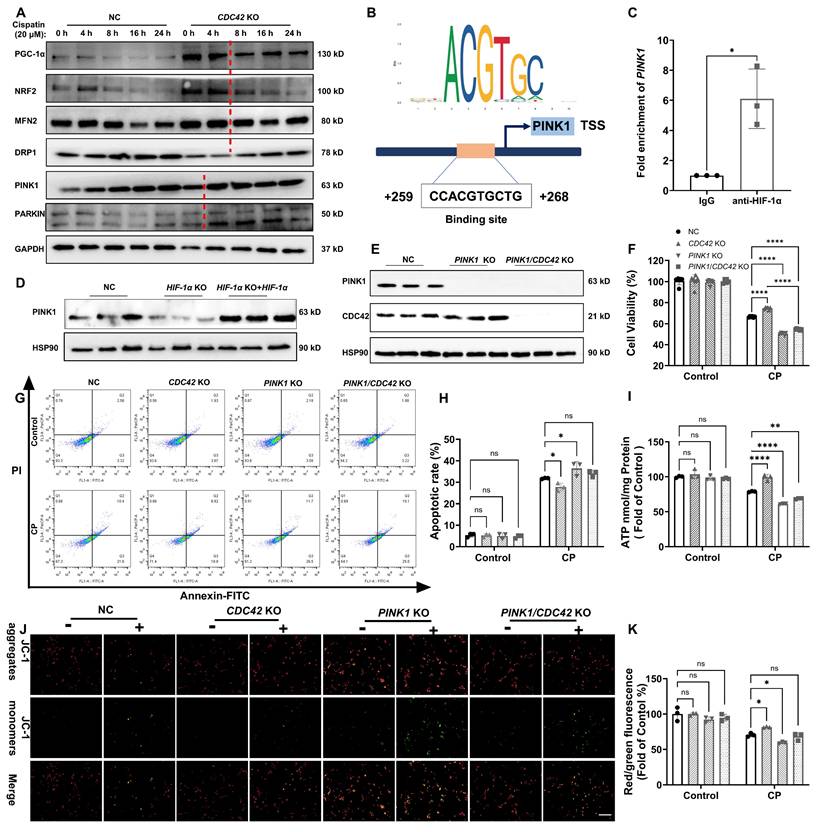

HIF-1α mediated mitochondrial function via transcriptional regulation of PINK1 in CP-induced AKI

Our study revealed that HIF-1α KO disrupts mitochondrial function, consistent with previous findings (45,46). To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying HIF-1α's role in mitochondrial homeostasis, we investigated whether mitochondrial biogenesis, fusion/fission, or mitophagy is the primary regulatory process by which CDC42 inhibition against AKI.

Time-course analysis of mitochondrial-related proteins in CDC42 KO and NC cells exposed to CP revealed that mitophagy-related proteins (PINK1, PARKIN) rapidly increased at 4 h, while mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC-1α, NRF2) and fusion/fission (MFN2, DRP1) proteins showed significant changes at 8 h (Figure 9A). This suggests that mitophagy is the initial step in mitochondrial regulation upon CDC42 inhibition. Using the JASPER database, we identified PINK1 as the most likely downstream gene of HIF-1α in mitochondrial-related genes (Supplementary Figure S7), validated by ChIP assay showing HIF-1α binding to the PINK1 promoter (Figure 9B-9C) and WB results indicating PINK1 expression is positively regulated by HIF-1α (Figure 9D). Collectively, these results support the conclusion that mitophagy is the key initial process in CDC42/KLF2/HIF-1α-mediated mitochondrial regulation.

PINK1 is a crucial sensor of mitochondrial damage, initiating mitophagy to protect cells from external stimulus-induced mitochondrial dysfunction (47). To confirm that CDC42 inhibition provided the protective effect against AKI through regulating KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 axis, we examined the impact of CP exposure in PINK1 KO cells and PINK1/CDC42 dKO cells (Figure 9E). As expected, PINK1 KO further exacerbated CP-induced cell injury and mitochondrial dysfunction, and more importantly, PINK1 KO inhibited the protective effect of CDC42 KO against CP-AKI in vitro (Figure 9F-9K). These findings suggest that PINK1 plays a crucial role in CDC42-mediated mitochondrial protection, supporting the hypothesis that CDC42 inhibition mitigates AKI by promoting mitophagy through KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 regulatory axis.

Discussion

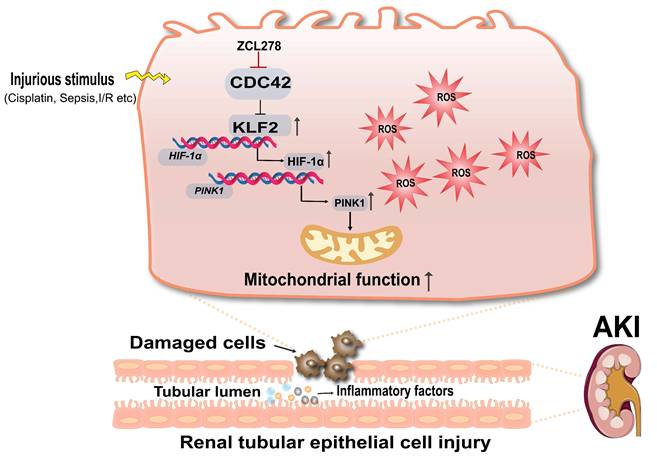

This study is the first to reveal that CDC42 inhibition significantly attenuated kidney injury in both CP- and I/R-induced AKI models. Mechanistically, we show that CDC42 inhibition protected RTECs in vivo and in vitro by mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress via activation of the KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1-mediated mitophagy pathway (Figure 10).

HIF-1α was the downstream target of KLF2 to regulate CP-induced cell damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in vitro. (A) Binding sites of KLF2 in the HIF-1 α promoter region were predicted using the JASPAR database; (B) ChIP experiments validated the transcriptional regulation of HIF-1a by KLF2 (n = 3); (C) KLF2 KO reduced HIF-1α protein expression in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (D) Renal Hif-1α protein expression was increased in I/R induced AKI mice and further increased after ZCL278 treatment (n = 3); (E) Renal Hif-1α protein expression was increased in Cdc42Cdh16 KD mice compared with Cdc42f/f mice (n = 3); (F) CDC42 KO increased HIF-1α protein expression in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (G) The knockout efficiency of HIF-1α in HK-2 cells was verified by WB (n = 3); (H) HIF-1α KO increased CP-induced decrease in cell viability compared to NC cells (n = 5); (I-J) Representative images of flow cytometry (I) and the related statistical analysis (J) showed that HIF-1α KO increased CP-induced cell apoptosis (n = 3); (K) HIF-1α KO increased the ROS accumulation in HK-2 cells (n = 3); (L) HIF-1α KO aggravated CP-induced reduction in cellular ATP levels cells (n = 3); (M-N) Representative images of the mitochondrial membrane potential (M) and the quantitative analyses of JC-1 fluorescence intensity (N) demonstrated that HIF-1α KO exacerbated the CP-induced decrease in MMP (n = 3, scale bar = 200 μm). Data were presented as means ± SD. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

To identify candidate drivers of AKI, we first analyzed scRNA-seq data from human AKI kidney (24). KEGG enrichment revealed activation pathways related to infection and, notably, actin cytoskeleton dynamics. Given that the AKI patients developed the disease in the context of critical illnesses, severe infections, and systemic inflammation, the enrichment in actin cytoskeleton dynamics signaling pathway was particularly striking. Among the three primary regulators of actin cytoskeletal remodeling (30), CDC42 exhibited the more pronounced dysregulation in PT cells compared to RHOA and RAC1, suggesting a central role in AKI. It is well known that CDC42 functions as a molecular switch to transduce upstream signals to downstream effectors (14-16,48), which renders it crucial for organ development (49) and disease pathogenesis (50,51), as evident by congenital defects and tumorigenesis in organ-specific knockout models (52). In oncology, CDC42 overexpression has been reported in gastric (19), colorectal (20), breast (21,22), and liver cancers (53-55), correlating with poor clinical outcomes and therapeutic resistance. Beyond cancer, CDC42 is indispensable for kidney development, as it is required for ciliogenesis in RTECs (18). Its deletion in podocyte induces congenital nephrotic syndrome (56), while in chronic kidney disease, it promotes vascular calcification and renal fibrosis (57). Despite these insights, its role in AKI pathogenesis stays unknown.

CDC42 inhibition improved mitochondrial function to protect against AKI by targeting PINK1. (A) A time course of mitochondrial homeostasis related proteins in NC and CDC42 KO cells showed that mitophagy (PINK1, PARKIN) might be the leading process among CP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction (n = 3); (B) Binding sites of HIF-1α in the PINK1 promoter region were predicted using the JASPAR database; (C) ChIP assays showed that HIF-1α transcriptionally regulated PINK1 (n = 3); (D) Re-expression of HIF-1α in HIF-1α KO cells restored the decline in PINK1 protein levels (n = 3); (E) PINK1 KO efficiency was verified in PINK1 KO cells and PINK1/CDC42 dKO cells (n = 3); (F-H) Protective effects of CDC42 KO in cell viability (F) (n = 6) and cell apoptosis (G-H) were counteracted by PINK1 KO (n = 3); Protective effects of CDC42 KO in CP-induced mitochondrial dysfunction were counteracted by PINK1 KO, as evident by mitochondrial ATP levels (I) and MMP levels (J-K, scale bar: 200 μm) (n = 3). Data were presented as means ± SD. * 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05, ** 0.001< p ≤ 0.01, *** 0.0001 <p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001.

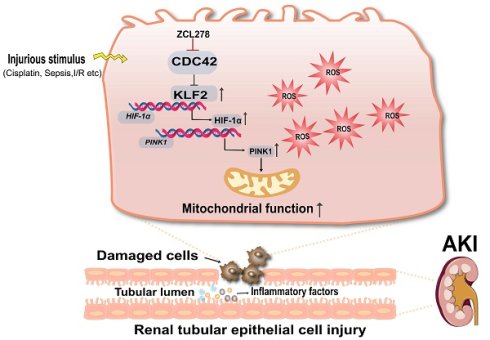

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism that CDC42 inhibition protects against AKI. Inhibition of CDC42 enhances KLF2 promoter activity, leading to the transcriptional upregulation of HIF-1α, which subsequently promotes PINK1 expression transcriptionally. Through activation of the KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 transcriptional cascade, CDC42 inhibition promotes mitophagy, restores mitochondrial homeostasis, and protects renal tubular epithelial cells from oxidative damage.

Our research showed CDC42 was upregulated in human AKI kidneys, murine models of CP- and I/R-induced AKI, and CP-treated HK-2 cells. The induction of Cdc42 was likely driven by the robust increase in inflammatory cytokines, particularly Il-6 (58), which was markedly elevated (~60-120 fold) in AKI mice kidneys. Importantly, both pharmacological inhibition and genetic blockage of Cdc42 attenuated renal dysfunction (Cr, BUN, and Kim-1), tubular injury, and inflammatory cytokines (Il-6, Il-1β, Tnf-α) expression. Parallel in vitro studies further validated the reno-protective effects of CDC42 inhibition across experimental systems.

Mitochondrial dysfunction and the ensuing oxidative burst are well-established drivers of RTEC injury in AKI (6-9), however the potential role of CDC42 in this process remains elusive. Notably, accumulating evidences shows that actin cytoskeleton dynamics are essential for modulating mitochondrial morphology and function (59). Furthermore, recent studies indicate that glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), a known downstream effector of CDC42 (60), acts as a key regulator of mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney injury (61,62). Although the participation of GSK3β in CDC42-mediated AKI remains to be further investigated, the crosstalk between CDC42, cytoskeletal remodeling, and mitochondrial function suggests that CDC42 inhibition likely ameliorates AKI by regulating mitochondrial homeostasis. Our in vivo and in vitro studies further validated this hypothesis: CDC42 was upregulated in renal mitochondria during AKI, with its inhibition restoring mitochondrial function by rescuing ATP production, membrane potential, and ultrastructure, along with the coordinated restoration of key homeostasis regulators (PGC-1α, NRF2, MNF2, DRP1, PINK1, and PARKIN).

Transcriptomic analysis identified KLF2 as a key downstream target of CDC42. KLF2 is a zinc finger transcription factor known to mitigate oxidative stress, inflammation, and thrombus activation (42). Previous studies have shown that KLF2 activation preserves mitochondrial function and attenuates ROS-induced damage by promoting mitophagy (40,41,63). In our study, CDC42 inhibition upregulated KLF2 expression via promoter activation, more importantly, KLF2 deficiency abrogated the mitochondria protection afforded by CDC42 inhibition, which establishing KLF2 as an essential mediator of the CDC42-mitochondrial axis.

Further mechanistic exploration revealed that KLF2 regulates HIF-1α transcription. ChIP assay demonstrated HIF-1α is transcriptionally regulated by KLF2 at the predicted promoter binding motif, and WB analyses demonstrated that KLF2-driven HIF-1α activation in response to CDC42 inhibition. HIF-1α is a transcription factor with critical role in hypoxia and mitochondrial protection. Activation of HIF-1α has been found to protect against AKI (64-67) by mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and autophagy (46,68,69). In addition, multiple lines of evidence, including transcriptional database prediction, ChIP, WB, and rescue assay, validated PINK1 was transcriptionally modulated by HIF-1α at the predicted promoter binding sites. Functionally, PINK1 deletion exacerbated mitochondrial dysfunction and abrogated the protective effect of CDC42 inhibition, consistent with its role as a key mitophagy regulator (7,70-74). Together, these findings establish a KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 axis through which CDC42 inhibition promotes mitophagy and preserves mitochondrial homeostasis.

In addition to mitophagy, CDC42 inhibition dampened inflammatory responses in AKI kidneys, consistent with prior studies linking CDC42 to chronic inflammatory conditions (75-78). However, the loss of protection in KLF2 or PINK1 deficient models indicates that mitophagy-mediated mitochondrial preservation is the predominant protective mechanism, with anti-inflammation and other factors as the secondary outcome.

Our findings also highlight the translational potential of targeting CDC42, which is consistently upregulated in human and experimental AKI, with its inhibition conferring robust renoprotection across models. As a multifunctional signaling hub, CDC42 offers a distinct mechanistic advantage over downstream-specific strategies such as soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) inhibitors (anti-inflammatory) (79) or HIF-PH inhibitors (hypoxia adaptation) (80), as well as single-target approaches like PGC-1α agonists (81). By coordinately modulating key processes, including inflammation (Figure 2G, Figure 3K), oxidative stress (Figure 4J, Figure 5F), and mitochondrial function (Figure 2K-2P, Figure 2U-2W, Figure 3M-3R), CDC42 inhibition elicits synergistic effects that enable more comprehensive restoration of mitochondrial homeostasis. The selective inhibitor ZCL278, which disrupts CDC42-Intersectin interaction to suppress CDC42-mediated signaling (32), showed preventive and therapeutic efficacy without nephrotoxicity in CP- and I/R-induced AKI. These effects were further validated in RTEC-specific Cdc42 knockdown mice, minimizing concerns regarding off-target actions and supporting CDC42 as a highly specific therapeutic target. Moreover, ZCL278 showed efficacy through multiple routes of administration, underscoring its preclinical feasibility (82). Although clinically approved CDC42-specific inhibitors are not yet available, several dual Rho GTPases inhibitors, such as R-ketorolac and R-naproxen (50,83,84), mitoxantrone (85), and MBQ-167 (86) have progressed into oncology trails. These developments suggest that targeting CDC42 in AKI is both feasible and promising, warranting further exploration.

In addition, we acknowledge that the present study has certain limitations. First, our AKI models are based on rodents, and their translational relevance to human clinical settings needs further verification using more diverse clinical AKI samples. Second, the molecular mechanism underlying CDC42-mediated enhancement of KLF2 promoter activity remains to be fully elucidated, as potential intermediate molecules may be involved.

In conclusion, our study identifies CDC42 as a pivotal regulator of AKI pathogenesis through its impact on mitochondrial function. By activating the KLF2/HIF-1α/PINK1 axis, CDC42 inhibition promotes mitophagy, restores mitochondrial homeostasis, and alleviates oxidative stress and renal injury. These findings provide mechanistic insight and translational rationale for developing CDC42-targeted and mitochondria-directed therapies for AKI.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods, figures and tables.

Acknowledgements

This project was co-supported by the Chongqing Municipal Natural Science Foundation-Education Commission Joint Fund for Innovation and Development Key Project (CSTB2022NSCQ-LZX0027), the Chongqing Education Committee University Innovation Research Group Grant (CXQT21016), and Chongqing Medical University startup grant.

Author contributions

X.Z. conceived and led the research, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. X.F. helped in measuring urea and creatinine concentrations. Y.-W.M., P.D., Q. J., H.-H. Y, Q.-J.P., K.-D. N, A.-Z.L., R.-Y.L. and Y.-Y. C. provided help in the animal experiments. Z.-G.L. helped in taking TEM micrographs and relevant analysis. H.-X.Y. helped analyze data and provided useful advice on this subject. J.-Y.L. initiated, conceived, and designed the research, supervised the experiments, secured funding, and critically revised and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Raw data from the RNA-seq analyses have been uploaded to the GEO under the accession number GSE274116. Since it remains in private status, to review GEO accession GSE274116: go to https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE274116, and enter token wzcvuywsffavneh into the box. Other data that generated or analyzed in this study were included in the main text and supplementary materials of this article. Uncropped full gel images of Western blot analyses are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Kellum JA, Romagnani P, Ashuntantang G, Ronco C, Zarbock A, Anders HJ. Acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 July 15;7(1):52

2. Moore PK, Hsu RK, Liu KD. Management of Acute Kidney Injury: Core Curriculum 2018. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018 July;72(1):136-48

3. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S. et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005Aug17;294(7):813-8

4. The Beijing Acute Kidney Injury Trial (BAKIT) workgroup, Jiang L, Zhu Y, Luo X, Wen Y, Du B. et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in intensive care units in Beijing: the multi-center BAKIT study. BMC Nephrol. 2019Dec;20(1):468

5. Fortrie G, De Geus HRH, Betjes MGH. The aftermath of acute kidney injury: a narrative review of long-term mortality and renal function. Crit Care. 2019Dec;23(1):24

6. Emma F, Montini G, Parikh SM, Salviati L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in inherited renal disease and acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016May;12(5):267-80

7. Tang C, Cai J, Yin XM, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA, Dong Z. Mitochondrial quality control in kidney injury and repair. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021May;17(5):299-318

8. Linkermann A, Chen G, Dong G, Kunzendorf U, Krautwald S, Dong Z. Regulated cell death in AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014Dec;25(12):2689-701

9. Zuk A, Bonventre JV. Acute Kidney Injury. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:293-307

10. Zhang X, Agborbesong E, Li X. The Role of Mitochondria in Acute Kidney Injury and Chronic Kidney Disease and Its Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2021Oct19;22(20):11253

11. Deng BQ, Luo Y, Kang X, Li CB, Morisseau C, Yang J. et al. Epoxide metabolites of arachidonate and docosahexaenoate function conversely in acute kidney injury involved in GSK3β signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017Nov21;114(47):12608-13

12. Luo Y, Wu MY, Deng BQ, Huang J, Hwang SH, Li MY. et al. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates a high-fat diet-mediated renal injury by activating PAX2 and AMPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019Mar12;116(11):5154-9

13. Hu D, Wu M, Chen G, Deng B, Yu H, Huang J. et al. Metabolomics analysis of human plasma reveals decreased production of trimethylamine N-oxide retards the progression of chronic kidney disease. British J Pharmacology. 2022 Sept;179(17):4344-59

14. Farhan H, Hsu VW. Cdc42 and Cellular Polarity: Emerging Roles at the Golgi. Trends Cell Biol. 2016Apr;26(4):241-8

15. Johnson DI. Cdc42: An essential Rho-type GTPase controlling eukaryotic cell polarity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999Mar;63(1):54-105

16. Cerione RA. Cdc42: new roads to travel. Trends Cell Biol. 2004Mar;14(3):127-32

17. Melendez J, Grogg M, Zheng Y. Signaling role of Cdc42 in regulating mammalian physiology. J Biol Chem. 2011Jan28;286(4):2375-81

18. Zuo X, Fogelgren B, Lipschutz JH. The Small GTPase Cdc42 Is Necessary for Primary Ciliogenesis in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011 June;286(25):22469-77

19. Li X, Jiang M, Chen D, Xu B, Wang R, Chu Y. et al. miR-148b-3p inhibits gastric cancer metastasis by inhibiting the Dock6/Rac1/Cdc42 axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018Mar27;37(1):71

20. Aikemu B, Shao Y, Yang G, Ma J, Zhang S, Yang X. et al. NDRG1 regulates Filopodia-induced Colorectal Cancer invasiveness via modulating CDC42 activity. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(7):1716-30

21. Pichot CS, Arvanitis C, Hartig SM, Jensen SA, Bechill J, Marzouk S. et al. Cdc42-interacting protein 4 promotes breast cancer cell invasion and formation of invadopodia through activation of N-WASp. Cancer Res. 2010Nov1;70(21):8347-56

22. He Y, Goyette MA, Chapelle J, Boufaied N, Al Rahbani J, Schonewolff M. et al. CdGAP is a talin-binding protein and a target of TGF-β signaling that promotes HER2-positive breast cancer growth and metastasis. Cell Rep. 2023Aug29;42(8):112936

23. Martinez-Lopez N, Mattar P, Toledo M, Bains H, Kalyani M, Aoun ML. et al. mTORC2-NDRG1-CDC42 axis couples fasting to mitochondrial fission. Nat Cell Biol. 2023 July;25(7):989-1003

24. Hinze C, Kocks C, Leiz J, Karaiskos N, Boltengagen A, Cao S. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals common epithelial response patterns in human acute kidney injury. Genome Med. 2022 Sept 9;14(1):103

25. Scholz H, Boivin FJ, Schmidt-Ott KM, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU, Scholl UI. et al. Kidney physiology and susceptibility to acute kidney injury: implications for renoprotection. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021May;17(5):335-49

26. Ho KM, Morgan DJR. The Proximal Tubule as the Pathogenic and Therapeutic Target in Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron. 2022;146(5):494-502

27. Hodge RG, Ridley AJ. Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016Aug;17(8):496-510

28. Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R, Sykes C, Plastino J. Actin dynamics, architecture, and mechanics in cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2014Jan;94(1):235-63

29. Yadav T, Gau D, Roy P. Mitochondria-actin cytoskeleton crosstalk in cell migration. J Cell Physiol. 2022May;237(5):2387-403

30. Tapon N, Hall A. Rho, Rac and Cdc42 GTPases regulate the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997Feb;9(1):86-92

31. Miao J, Zhu H, Wang J, Chen J, Han F, Lin W. Experimental models for preclinical research in kidney disease. Zool Res. 2024 Sept 18;45(5):1161-74

32. Friesland A, Zhao Y, Chen YH, Wang L, Zhou H, Lu Q. Small molecule targeting Cdc42-intersectin interaction disrupts Golgi organization and suppresses cell motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013Jan22;110(4):1261-6

33. Chen Z, Li Y, Yuan Y, Lai K, Ye K, Lin Y. et al. Single-cell sequencing reveals homogeneity and heterogeneity of the cytopathological mechanisms in different etiology-induced AKI. Cell Death Dis. 2023May11;14(5):318

34. Schrezenmeier EV, Barasch J, Budde K, Westhoff T, Schmidt-Ott KM. Biomarkers in acute kidney injury - pathophysiological basis and clinical performance. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2017Mar;219(3):554-72

35. Xiao Z, Huang Q, Yang Y, Liu M, Chen Q, Huang J. et al. Emerging early diagnostic methods for acute kidney injury. Theranostics. 2022;12(6):2963-86

36. Arany I, Safirstein RL. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Semin Nephrol. 2003 Sept;23(5):460-4

37. Havasi A, Borkan SC. Apoptosis and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2011 July;80(1):29-40

38. Li J, Xu Z, Jiang L, Mao J, Zeng Z, Fang L. et al. Rictor/mTORC2 protects against cisplatin-induced tubular cell death and acute kidney injury. Kidney International. 2014 July;86(1):86-102

39. Van Angelen AA, Glaudemans B, Van Der Kemp AWCM, Hoenderop JGJ, Bindels RJM. Cisplatin-induced injury of the renal distal convoluted tubule is associated with hypomagnesaemia in mice. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2013Apr;28(4):879-89

40. Maity J, Barthels D, Sarkar J, Prateeksha P, Deb M, Rolph D. et al. Ferutinin induces osteoblast differentiation of DPSCs via induction of KLF2 and autophagy/mitophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2022May12;13(5):452

41. Maity J, Deb M, Greene C, Das H. KLF2 regulates dental pulp-derived stem cell differentiation through the induction of mitophagy and altering mitochondrial metabolism. Redox Biol. 2020 Sept;36:101622

42. Rane MJ, Zhao Y, Cai L. Krϋppel-like factors (KLFs) in renal physiology and disease. EBioMedicine. 2019Feb;40:743-50

43. Ratnadiwakara M, Änkö ML. mRNA Stability Assay Using transcription inhibition by Actinomycin D in Mouse Pluripotent Stem Cells. Bio Protoc. 2018Nov5;8(21):e3072

44. Gonzalez FJ, Xie C, Jiang C. The role of hypoxia-inducible factors in metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018Dec;15(1):21-32

45. Li HS, Zhou YN, Li L, Li SF, Long D, Chen XL. et al. HIF-1α protects against oxidative stress by directly targeting mitochondria. Redox Biol. 2019 July;25:101109

46. Fu ZJ, Wang ZY, Xu L, Chen XH, Li XX, Liao WT. et al. HIF-1α-BNIP3-mediated mitophagy in tubular cells protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Redox Biol. 2020 Sept;36:101671

47. Narendra DP, Youle RJ. The role of PINK1-Parkin in mitochondrial quality control. Nat Cell Biol. 2024Oct;26(10):1639-51

48. Takai Y, Sasaki T, Matozaki T. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol Rev. 2001Jan;81(1):153-208

49. Melendez J, Grogg M, Zheng Y. Signaling Role of Cdc42 in Regulating Mammalian Physiology. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011Jan;286(4):2375-81

50. Maldonado MDM, Dharmawardhane S. Targeting Rac and Cdc42 GTPases in Cancer. Cancer Res. 2018 June 15;78(12):3101-11

51. Jansen S, Gosens R, Wieland T, Schmidt M. Paving the Rho in cancer metastasis: Rho GTPases and beyond. Pharmacol Ther. 2018Mar;183:1-21

52. van Hengel J, D'Hooge P, Hooghe B, Wu X, Libbrecht L, De Vos R. et al. Continuous cell injury promotes hepatic tumorigenesis in cdc42-deficient mouse liver. Gastroenterology. 2008Mar;134(3):781-92

53. López-Luque J, Bertran E, Crosas-Molist E, Maiques O, Malfettone A, Caja L. et al. Downregulation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in hepatocellular carcinoma facilitates Transforming Growth Factor-β-induced epithelial to amoeboid transition. Cancer Lett. 2019Nov1;464:15-24

54. Zhang J, Yang C, Gong L, Zhu S, Tian J, Zhang F. et al. RICH2, a potential tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2019 June 1;24(8):1363-76

55. Yang X, Liu Z, Li Y, Chen K, Peng H, Zhu L. et al. Rab5a promotes the migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma by up-regulating Cdc42. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018;11(1):224-31

56. Huang Z, Zhang L, Chen Y, Zhang H, Zhang Q, Li R. et al. Cdc42 deficiency induces podocyte apoptosis by inhibiting the Nwasp/stress fibers/YAP pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2016Mar17;7(3):e2142-e2142

57. Li Z, Wu J, Zhang X, Ou C, Zhong X, Chen Y. et al. CDC42 promotes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. The Journal of Pathology. 2019Dec;249(4):461-71

58. Niu L, Chang J, Liu S, Shen J, Li X, Guo Y. et al. Tetrandrine induces cell cycle arrest in cutaneous melanoma cells by inhibiting IL-6/CDC42 signaling. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025Feb20;317(1):442

59. Illescas M, Peñas A, Arenas J, Martín MA, Ugalde C. Regulation of Mitochondrial Function by the Actin Cytoskeleton. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:795838

60. Etienne-Manneville S, Hall A. Cdc42 regulates GSK-3beta and adenomatous polyposis coli to control cell polarity. Nature. 2003Feb13;421(6924):753-6

61. Wang Z, Ge Y, Bao H, Dworkin L, Peng A, Gong R. Redox-sensitive glycogen synthase kinase 3β-directed control of mitochondrial permeability transition: rheostatic regulation of acute kidney injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013Dec;65:849-58

62. Wang Z, Bao H, Ge Y, Zhuang S, Peng A, Gong R. Pharmacological targeting of GSK3β confers protection against podocytopathy and proteinuria by desensitizing mitochondrial permeability transition. Br J Pharmacol. 2015Feb;172(3):895-909

63. Chen F, Zhan J, Liu M, Mamun AA, Huang S, Tao Y. et al. FGF2 Alleviates Microvascular Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by KLF2-mediated Ferroptosis Inhibition and Antioxidant Responses. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(13):4340-59

64. Rosenberger C, Rosen S, Shina A, Frei U, Eckardt KU, Flippin LA. et al. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factors ameliorates hypoxic distal tubular injury in the isolated perfused rat kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008Nov;23(11):3472-8

65. Bernhardt WM, Câmpean V, Kany S, Jürgensen JS, Weidemann A, Warnecke C. et al. Preconditional activation of hypoxia-inducible factors ameliorates ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006 July;17(7):1970-8

66. Li X, Jiang B, Zou Y, Zhang J, Fu YY, Zhai XY. Roxadustat (FG-4592) Facilitates Recovery From Renal Damage by Ameliorating Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by Folic Acid. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:788977

67. Yang Y, Yu X, Zhang Y, Ding G, Zhu C, Huang S. et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor roxadustat (FG-4592) protects against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018Apr16;132(7):825-38

68. Chun N, Coca SG, He JC. A protective role for microRNA-688 in acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2018Dec3;128(12):5216-8

69. Qiu S, Chen X, Pang Y, Zhang Z. Lipocalin-2 protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice through autophagy activation mediated by HIF1α and NF-κb crosstalk. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018Dec;108:244-53

70. Bhargava P, Schnellmann RG. Mitochondrial energetics in the kidney. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017Oct;13(10):629-46

71. Matsuda N, Sato S, Shiba K, Okatsu K, Saisho K, Gautier CA. et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010Apr19;189(2):211-21

72. Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RLA, Kim J. et al. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010Jan5;107(1):378-83

73. Geisler S, Holmström KM, Treis A, Skujat D, Weber SS, Fiesel FC. et al. The PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is compromised by PD-associated mutations. Autophagy. 2010Oct;6(7):871-8

74. Chen C, Qin S, Song X, Wen J, Huang W, Sheng Z. et al. PI3K p85α/HIF-1α accelerates the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension by regulating fatty acid uptake and mitophagy. Mol Med. 2024Nov11;30(1):208

75. Florian MC, Leins H, Gobs M, Han Y, Marka G, Soller K. et al. Inhibition of Cdc42 activity extends lifespan and decreases circulating inflammatory cytokines in aged female C57BL/6 mice. Aging Cell. 2020 Sept;19(9):e13208

76. McSweeney KR, Gadanec LK, Qaradakhi T, Ali BA, Zulli A, Apostolopoulos V. Mechanisms of Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury: Pathological Mechanisms, Pharmacological Interventions, and Genetic Mitigations. Cancers. 2021Mar29;13(7):1572

77. Ma X, Liu H, Zhu J, Zhang C, Peng Y, Mao Z. et al. miR-185-5p Regulates Inflammation and Phagocytosis through CDC42/JNK Pathway in Macrophages. Genes (Basel). 2022Mar7;13(3):468

78. Ming X, Yang F, Zhu H. Blood CDC42 overexpression is associated with an increased risk of acute exacerbation, inflammation and disease severity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp Ther Med. 2022 Sept;24(3):544

79. Zhang J, Luan ZL, Huo XK, Zhang M, Morisseau C, Sun CP. et al. Direct targeting of sEH with alisol B alleviated the apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(1):294-310

80. Gupta N, Wish JB. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors: A Potential New Treatment for Anemia in Patients With CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 June;69(6):815-26

81. Fontecha-Barriuso M, Martin-Sanchez D, Martinez-Moreno JM, Monsalve M, Ramos AM, Sanchez-Niño MD. et al. The Role of PGC-1α and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Kidney Diseases. Biomolecules. 2020Feb24;10(2):347

82. Zhang Q, Qin Z, Wang Q, Lu L, Wang J, Lu M. et al. Pharmacokinetic profiling of ZCL-278, a cdc42 inhibitor, and its effectiveness against chronic kidney disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2024Oct;179:117329

83. Oprea TI, Sklar LA, Agola JO, Guo Y, Silberberg M, Roxby J. et al. Novel Activities of Select NSAID R-Enantiomers against Rac1 and Cdc42 GTPases. Olson MF, editor. PLoS ONE. 2015Nov11;10(11):e0142182

84. Guo Y, Kenney SR, Muller CY, Adams S, Rutledge T, Romero E. et al. R-Ketorolac Targets Cdc42 and Rac1 and Alters Ovarian Cancer Cell Behaviors Critical for Invasion and Metastasis. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2015Oct1;14(10):2215-27

85. Bidaud-Meynard A, Arma D, Taouji S, Laguerre M, Dessolin J, Rosenbaum J. et al. A novel small-molecule screening strategy identifies mitoxantrone as a RhoGTPase inhibitor. Biochemical Journal. 2013Feb15;450(1):55-62

86. Medina JI, Cruz-Collazo A, Maldonado MDM, Matos Gascot T, Borrero-Garcia LD, Cooke M. et al. Characterization of Novel Derivatives of MBQ-167, an Inhibitor of the GTP-binding Proteins Rac/Cdc42. Cancer Research Communications. 2022Dec29;2(12):1711-26

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Jun-Yan Liu, CNTTI of College of Pharmacy, Chongqing 400016, China. ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3018-0335; Tel: +86-23-6848 3587; E-mail address: jyliuedu.cn.

Corresponding author: Jun-Yan Liu, CNTTI of College of Pharmacy, Chongqing 400016, China. ORCID ID: 0000-0002-3018-0335; Tel: +86-23-6848 3587; E-mail address: jyliuedu.cn.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact