Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(3):1480-1495. doi:10.7150/ijbs.127857 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Classic Protocadherin PCDH10 Functions as a Tumor Suppressive Scaffold Protein Antagonizing Oncogenic WNT/β-catenin Signaling in Breast Carcinogenesis

1. Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery, Chongqing Key Laboratory of Molecular Oncology and Epigenetics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China.

2. Department of Breast Surgery, Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China.

3. Cancer Epigenetics Laboratory, Department of Clinical Oncology, State Key Laboratory of Translational Oncology, Sir YK Pao Center for Cancer, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China.

*Authors contributed equally to this work as first authors.

Received 2025-11-4; Accepted 2025-12-28; Published 2026-1-8

Abstract

Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, frequently inactivate tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) in multiple tumorigeneses. This study investigated the molecular basis of the tumor-suppressive role of the classic protocadherin tumor suppressor PCDH10 in breast carcinogenesis. Frequent PCDH10 downregulation and promoter methylation was identified in breast cancer, correlating with poor prognosis and ER-negative status. Restoration of PCDH10 expression significantly suppressed tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo, by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stemness. RNA sequencing revealed PCDH10's role in Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppression. Mechanistically, PCDH10 enhanced GSK-3β phosphorylation at Try216, inhibited aberrant β-catenin activation and upregulated the expression of the tumor-suppressive nuclear envelope protein LMNA expression through direct binding. Concurrently, it also attenuated other oncogenic signaling via suppression of RhoA and Akt phosphorylation. Collectively, promoter CpG methylation-mediated silencing of PCDH10 promotes breast cancer progression. PCDH10 restoration antagonizes tumorigenesis by dual blockade of Wnt/β-catenin and Akt signaling pathways through interactions with GSK-3β, β-catenin, and LMNA, as a scaffold protein. Our findings reveal a novel PCDH10-dependent tumor-suppressive axis and highlight its potential as a therapeutic target and biomarker in breast cancer.

Keywords: PCDH10, tumor suppressor gene, methylation, breast cancer, WNT signaling

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most common malignancy and second leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide [1]. While diagnostic methods and adjuvant therapies have advanced considerably [2], the molecular pathogenesis of breast cancer remains incompletely understood. Carcinogenesis is a multi-step process that involves accumulated multiple epigenetic and genetic alterations [3], with epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes (TSG) playing a critical role. Aberrant methylation of CpG islands (CGI) in TSG promoters represents a predominant epigenetic inactivation mechanism, triggering recruitment of repressive chromatin complexes and transcriptional silencing [4]. Notable TSGs silenced by promoter methylation in breast cancer include RASA5 [5], HOXA5 [6], DLEC1 [7], RASSF1A [8], and ZDHHC1 [9], underscoring the significance of epigenetic dysregulation in breast carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, further mechanistic insights are required for breast cancer study.

PCDH10, a member of the protocadherin subfamily within the cadherin superfamily, regulates cell-cell adhesion and signaling [10-12]. Our prior work identified PCDH10 as an epigenetically silenced novel TSG, as the first protocadherin gene with repressive cancer-associated promoter hypermethylation, in multiple cancers [13, 14]. Later, it was found that PCDH10 suppresses tumorigenesis through modulating oncogenic pathways such as EGFR/AKT in colorectal cancer [15], and PI3K/AKT in hepatocellular carcinoma [16]. In breast cancer, PCDH10 promoter methylation occurs frequently and shows promise as a diagnostic biomarker [17, 18]. However, its functional consequences, clinical relevance, and molecular mechanistic contributions to breast cancer pathogenesis remain poorly defined.

Thus, this study comprehensively investigates the clinical and functional significance of PCDH10 in breast carcinogenesis. We delineate its tumor-suppressive mechanisms, evaluate the clinical relevance of its promoter methylation in disease progression, and dissect its functional interplay with core oncogenic pathways.

Results

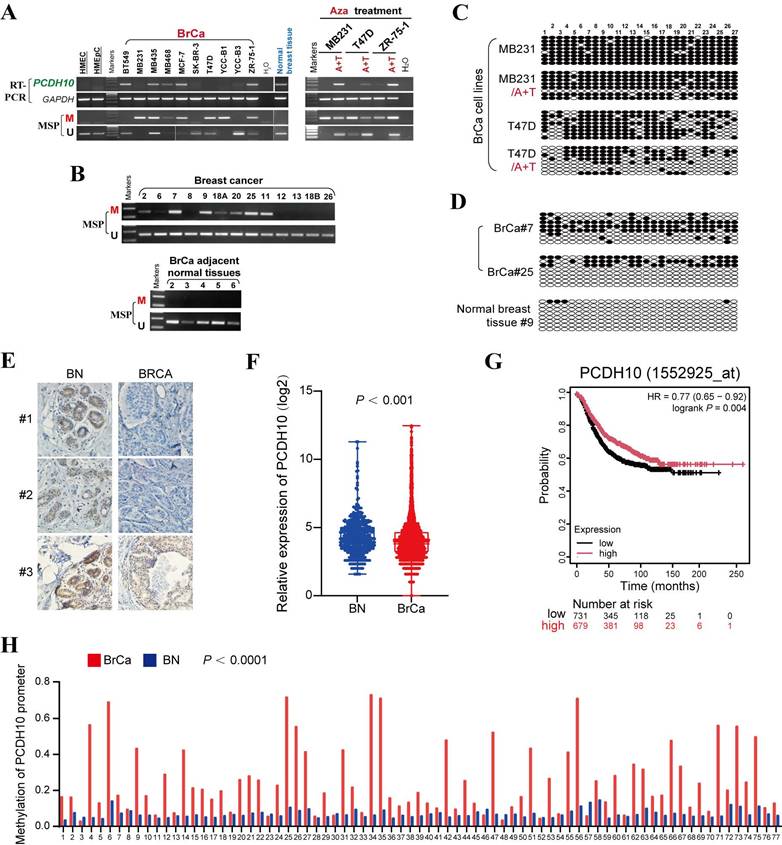

PCDH10 is frequently downregulated and methylated in breast cancer

To investigate the epigenetic regulation of PCDH10 in breast cancer, PCDH10 mRNA expression was first analyzed. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed that PCDH10 transcript levels were reduced or silenced in 6/10 (60%) breast cancer cell lines, whereas robust expression was observed in normal breast tissue (Fig. 1A). Subsequent promoter methylation analysis by methylation-specific PCR (MSP) demonstrated PCDH10 promoter methylation in 6/10 (60%) cell lines with absent or reduced expression (Fig. 1A), suggesting a strong correlation between PCDH10 promoter methylation and its transcriptional silencing. To further investigate whether promoter methylation is directly responsible for PCDH10 silencing, breast cell lines MDA-MB-231, T-47D, and ZR-75-1 were treated with 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Aza), a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, and Trichostatin A (TSA), a histone deacetylase inhibitor. This combined treatment aims to reactivate epigenetically silenced genes by reversing DNA hypermethylation and promoting a transcriptionally permissive chromatin state. Notably, the treatment dramatically restored PCDH10 expression, while MSP analyses showed a concomitant decrease in methylated alleles and an increase in unmethylated alleles (Fig. 1A). Clinical validation studies revealed PCDH10 promoter methylation in 43/52 (83%) primary breast tumor samples, but not in adjacent non-tumor tissues (0/5) (Fig. 1B, Table 1). Furthermore, bisulfite genomic sequencing (BGS) confirmed dense CpG island methylation in representative tumors (cases 7 and 25), in contrast to minimal methylation in a normal tissue sample (case 9) (Fig. 1C, D). Consistent with the observed transcriptional repression in tumors, immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated reduced cytoplasmic PCDH10 expression in breast tumor samples compared with normal tissues (Fig. 1E). Bioinformatics validation using the GENT2 database confirmed reduced PCDH10 expression in breast cancer tissues compared to normal controls (Fig. 1F), and survival analysis revealed a better prognosis for patients with higher PCDH10 expression (Fig. 1G). Analysis of TCGA data further revealed an association of higher PCDH10 expression levels with ER-positive status (Table 2). Finally, MethHC database analysis corroborated our findings of increased PCDH10 promoter methylation in breast cancer tissues versus normal tissues (Fig. 1H).

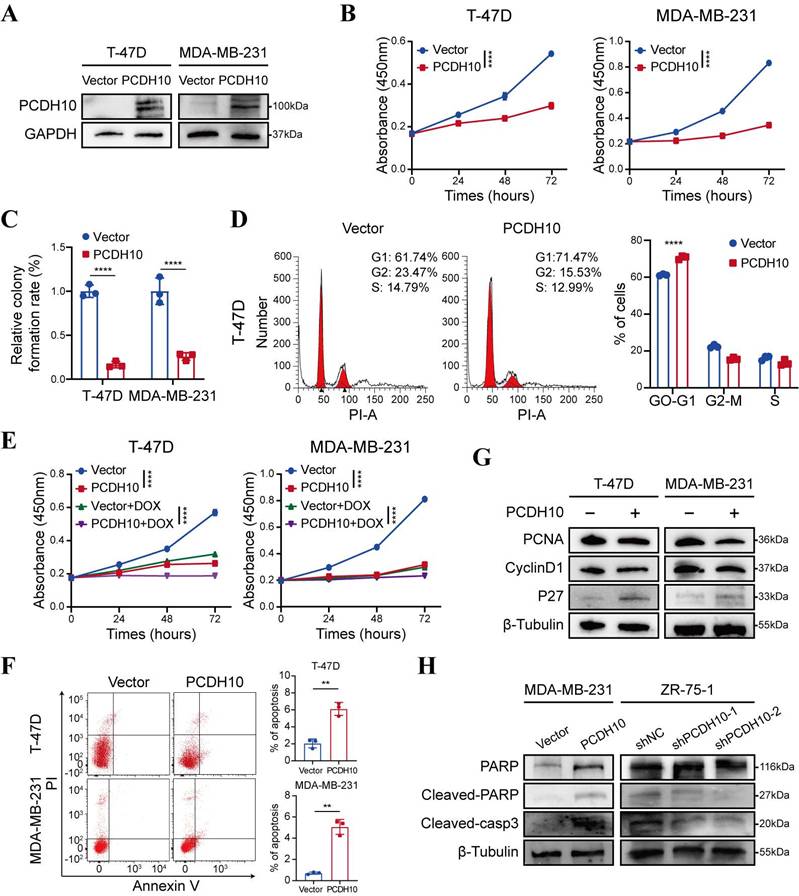

Restoration of PCDH10 suppresses breast tumor cell growth

Promoter methylation-regulated disruption of PCDH10 in breast cancer tissues and lack of this silencing in normal breast tissues suggested that PCDH10 may be a functional TSG in breast cancer. A mammalian expression vector encoding PCDH10 was transfected into breast cancer cells to further explore the effects of PCDH10 on tumor biological functions. Based on RT-PCR results, both T-47D and MDA-MB-231 showed loss of PCDH10 expression (Fig. 1A). These two cell lines were selected for constructing cells with stably expressed PCDH10. T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with vector or PCDH10 plasmid, and transfection efficiency was further examined by Western blot (WB) (Fig. 2A). Proliferation of breast tumor cells was significantly suppressed by ectopic expression of PCDH10 (Fig. 2B). Monolayer colony formation assays were applied to determine their colony formation abilities. PCDH10 expression significantly reduced the colony formation of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2C, Fig. S1A). To investigate the mechanism underlying the growth-suppressive effect of PCDH10, cell cycle and apoptosis assays were performed by flow cytometry (FC). The results demonstrated that PCDH10 restoration increased cells in G0/G1 phase (Fig. 2D, Fig. S1B-C), enhanced their sensitivity to doxorubicin (Fig. 2E), and promoted baseline apoptosis (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, WB analyses suggested that PCDH10 expression downregulated PCNA and cyclin D1 [19], and upregulated p27 expression [20] (Fig. 2G). Therefore, PCDH10 may contribute to growth inhibition and cell cycle arrest through associated pathways. Consistent with its pro-apoptotic role, PCDH10 restoration increased cleaved caspase-3 levels and cleaved-PARP in MDA-MB-231, whereas PCDH10 knockdown in ZR-75-1 attenuated apoptosis, decreasing both cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved-PARP levels (Fig. 2H). Collectively, these data establish PCDH10 as a growth-suppressing tumor suppressor in breast cancer in vitro.

PCDH10 is downregulated by promoter methylation in breast cancer. A PCDH10 mRNA expression level was detected by RT-PCR in breast cancer cell lines and normal breast tissues. PCDH10 promoter methylation status was detected by MSP. mRNA expression and promoter methylation were further detected by RT-PCR and MSP in MDA-MB-231, T-47D, and ZR-75-1 with Aza and TSA treatment. A: Aza. T: TSA. B Representative MSP results of PCDH10 in breast cancer and adjacent normal breast tissue samples. M, methylated; U: unmethylated. C BGS showing high-resolution mapping of methylation status of every CpG site within PCDH10 promoter in A+T-treated MDA-MB-231 and T-47D. D BGS determining methylation status of every CpG site in representative breast cancer and normal breast samples. E IHC staining of breast cancer and normal breast tissues. F Online database GENT2 was used to examine PCDH10 expression in normal breast and breast cancer. G Effect of PCDH10 expression on survival in breast cancer patients based on Kaplan-Meier. H Analysis of PCDH10 promoter methylation status in breast cancer and normal breast based on METHC. RT-PCR: semi-quantitative (RT)-PCR; MSP: Methylation-specific PCR; BrCa: breast cancer; BN: normal breast.

PCDH10 promoter methylation status in primary breast tumors

| Samples | PCDH10 promoter | Frequency of methylation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation | Unmethylation | ||

| BrCa (n=52) | 43 | 9 | 83% |

| BA (n=5) | 0 | 5 | 0% |

| BNP (n=14) | 2 | 12 | 14% |

Note: BA, breast cancer adjacent tissues; BrCa, breast cancer; BNP, breast normal tissues.

Relationship between clinicopathological features and PCDH10 expression in breast cancer patients (TCGA)

| Clinicopathological features | Cases (n=600) | Low expression | High expression | X2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.02 | 0.63 | |||

| > 55 | 351 | 172(49.0%) | 179 (51.0%) | ||

| < 55 | 249 | 127(51.0%) | 122(49.00%) | ||

| ER | 0.146 | <0.001 | |||

| Negative | 134 | 85 (63.4%) | 49 (36.6%) | ||

| Positive | 466 | 214(45.9%) | 252 (54.1%) | ||

| NULL=0 | |||||

| PR | 0.067 | 0.102 | |||

| Negative | 190 | 104(54.7%) | 86 (45.3%) | ||

| Positive | 410 | 193(47.1%) | 217 (52.9%) | ||

| NULL=0 | 0.019 | 0.651 | |||

| HER2 | |||||

| Negative | 500 | 252(50.4%) | 248 (49.6%) | ||

| Positive | 92 | 44 (47.8%) | 48 (52.2%) | ||

| NULL=8 | |||||

| Metastasis | 0.036 | 0.374 | |||

| M0 | 585 | 292(49.9%) | 293 (50.1%) | ||

| M1 | 11 | 4 (36.4%) | 7 (63.6%) | ||

| NULL=4 | |||||

| Stage (AJCC) | 0.007 | 0.876 | |||

| I-II | 447 | 224(50.11%) | 223(49.89%) | ||

| III-IV | 144 | 71 (49.31%) | 73 (50.69%) | ||

| NULL=9 |

Note. Null* Indeterminate / equivocal; PR: progesterone receptor; ER: estrogen receptor; HER2: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

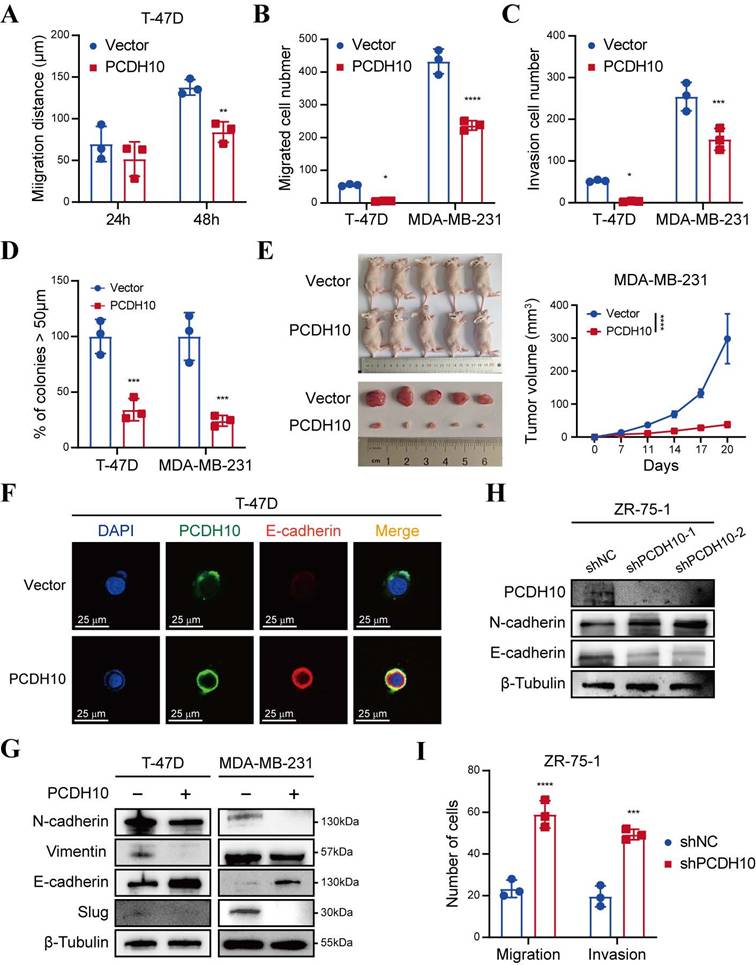

Ectopic expression of PCDH10 inhibits breast tumorigenesis and metastasis by suppressing EMT

To delineate the anti-metastatic function of PCDH10, we performed wound healing and Transwell® assays. Notably, PCDH10-expressing cells exhibited significantly delayed wound closure, compared to control groups (Fig. 3A, Fig. S2A-B). Consistent with this, Transwell® assays revealed significant suppression of migratory and invasive capacities, respectively (Fig. 3B-C, Fig. S2C). Spheroid-forming assay was performed to determine stemness potential, and results showed that PCDH10 overexpression lowered the spheroid-forming rates of breast tumor cells (Fig. 3D, Fig. S3A). In vivo, PCDH10 expression inhibited breast tumor development by reducing both tumor volume and weight (Fig. 3E, Fig. S3B). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays a crucial role in tumor formation and metastasis [21-22]. The hallmark features of EMT include loss of E-cadherin and gain of N-cadherin and Vimentin, which endow tumor cells with enhanced invasiveness and metastatic potential. To investigate the role of PCDH10 in this process, we examined the expression of these markers in mouse tumor tissues. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) revealed that PCDH10 restoration was associated with decreased N-cadherin but increased E-cadherin levels, which correlated with reduced tumor invasiveness and metastatic capacity (Fig. S3C). These findings were further confirmed by immunofluorescence (IF) staining of tumor cells (Fig. 3F, Fig. S3D). Subsequently, we performed WB analysis to detect EMT-related markers. Consistent with IHC results, expression of mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and Vimentin was downregulated in the PCDH10-restored group, whereas epithelial marker E-cadherin was upregulated (Fig. 3G). Additionally, expression of slug, a known EMT-inducing transcription factor, was also decreased (Fig. 3G). In contrast, in ZR-75-1, PCDH10 knockdown led to increased N-cadherin and decreased E-cadherin expression, accompanied by enhanced cell migration and invasion (Fig. 3H, I, Fig. S3E). These results demonstrate that PCDH10 inhibits tumor progression by suppressing the EMT process.

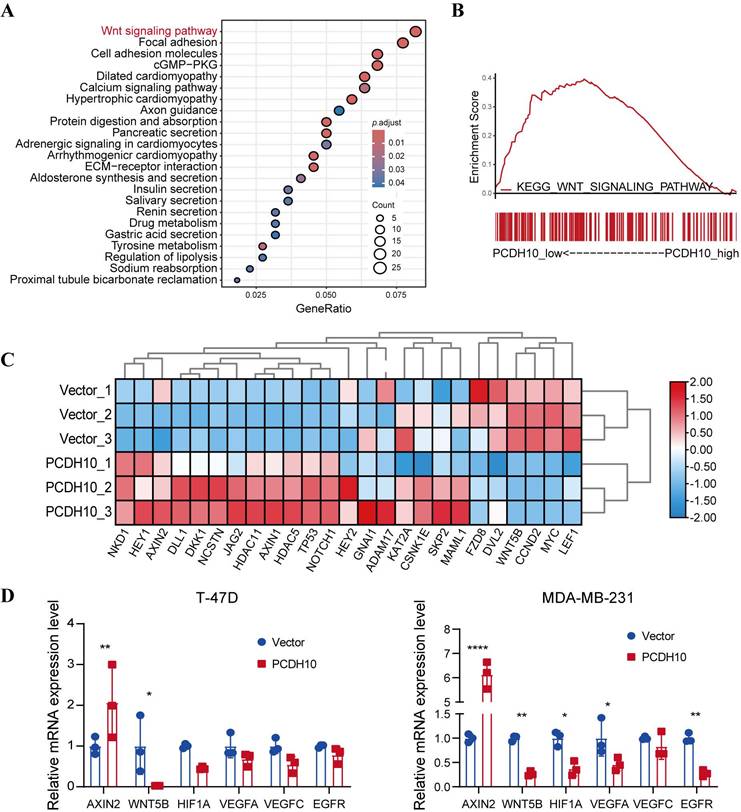

PCDH10 inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by modulating negative feedback factors and key components

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying PCDH10-mediated tumor suppression, we conducted RNA sequencing after PCDH10 restoration. KEGG analysis revealed that PCDH10 perturbation is associated with multiple cancer-related signaling pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin (Fig. 4A). Confirming this association and extending prior findings linking PCDH10 to Wnt signaling [23, 24], GSEA indicated that high PCDH10 expression downregulates Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Fig. 4B). Therefore, we focused on Wnt/β-catenin pathway-related target genes from our RNA sequencing data. Results showed that PCDH10 restoration upregulated the expression of Wnt/β-catenin negative regulators such as NKD1, AXIN2, and DLL1, while downregulating the expression of Wnt receptor FZD8 and transcriptional activator LEF1 (Fig. 4C). Subsequent qRT-PCR analysis validated the effects of PCDH10 on the expression of these genes associated with Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Specifically, the expression of AXIN2 was upregulated, while the expression of WNT5B [25], HIF1A [26], VEGFA, VEGFC [27], and EGFR [28] were downregulated (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that PCDH10 inhibits the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by upregulating negative regulators and downregulating key activators.

PCDH10 expression inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells. A WB detecting ectopic expression of PCDH10 in breast cancer cells line T-47D and MDA-MB-231. B CCK8 determining proliferation of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells in vector versus PCDH10-overexpressing (PCDH10-OE) group (n=3, two-way ANOVA). C Statistical analysis of colony formation of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells in vector versus PCDH10-OE group (n=3, two-way ANOVA). D Representative figures of cell cycle examined by FC (left) and statistical analysis of cell cycle (right) of T-47D cells in vector versus PCDH10-OE group (n=3, two-way ANOVA). E CCK8 determining effects of DOXO on breast cancer proliferation of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells in vector versus PCDH10-OE group (n=3, two-way ANOVA). F Representative plots of apoptosis assay determined by FC (left) and statistics analysis (right) of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells in vector versus PCDH10-OE group (n=3, t test). G Western blot analysis of PCNA, CyclinD1 and p27 in vector versus PCDH10-OE T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. H Western blot analysis of PARP, Cleaved-PARP, and Cleaved-casp3 in vector versus PCDH10-OE MDA-MB-231 cells and shNC versus shPCDH10 ZR-75-1 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD; Each dot represents one sample; *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.****p < 0.0001. CCK8: Cell Counting Kit-8. FC: flow cytometry. NC, negative control. RT-PCR, semi-quantitative (RT)-PCR. WB, Western Blot. DOXO, Doxorubicin.

PCDH10 expression suppresses metastasis in vitro and inhibits tumorigenesis in vivo. A-C Statistical analysis of wound healing assay (A), migration assay (B) and invasion assay (C) of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells in vector versus PCDH10-OE group (n=3, two-way ANOVA). D Cell spheroid-forming assay determining effect of PCDH10 on stemness potential of T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (n=3, two-way ANOVA). E MDA-MB-231 tumor growth in nude mice implanted with vector versus PCDH10-OE cells (n=5, two-way ANOVA). All the mice harvested on day 20 with the tumors arranged in volume order. F IF staining showed representative images of PCDH10 (green) and E-cadherin (red) in T-47D cells. G Western blot analysis of N-cadherin, Vimentin, E-cadherin, and Slug in vector versus PCDH10-OE T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. H Western blot analysis of PCDH10, N-cadherin and E-cadherin in shNC versus shPCDH10 ZR-75-1 cells. I Statistical analysis of migration and invasion assay in shNC versus shPCDH10 ZR-75-1 cells (n=3, two-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean ± SD; Each dot represents one sample. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.****p < 0.0001.

Ectopic PCDH10 expression inhibits EMT and downregulates multiple oncogenes in breast cancer cells. A KEGG analysis of mRNA-seq data showing the enriched signaling pathways in MDA-MB-231 from vector groups, in comparison to those from PCDH10-OE groups. B GSEA enrichment analysis based on mRNA-seq data in MDA-MB-231 from vector groups, in comparison to those from PCDH10-OE groups. C Heatmap of β-catenin signaling pathway-associated genes based on mRNA sequencing data. D qRT-PCR exploring PCDH10 effects on AXIN2, WNT5B, HIF1A, VEGFA, VEGFC, EGFR expression in both T-47D and MDA-MB-231 (n=3, two-way ANOVA). Data are presented as mean ± SD; Each dot represents one sample. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.****p < 0.0001.

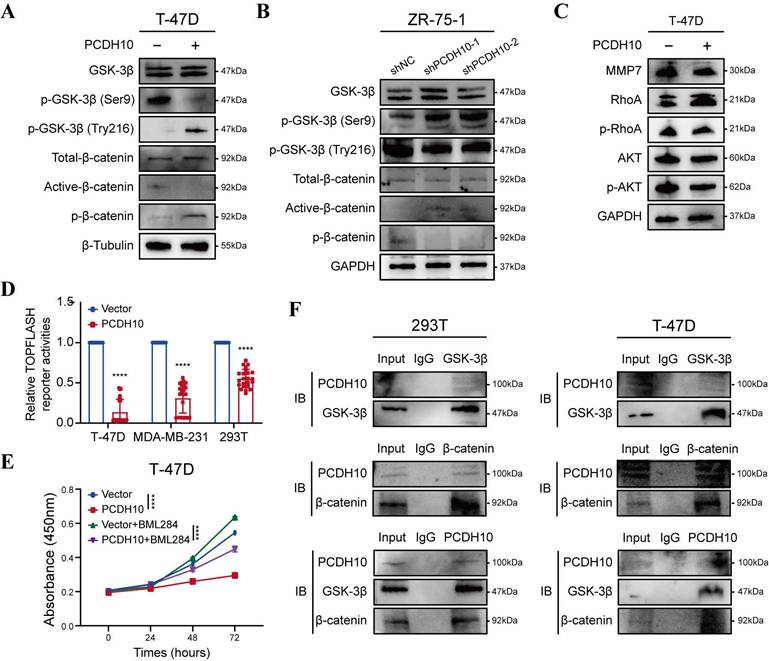

PCDH10 negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling via GSK-3β/β-catenin axis and protein-protein interactions

To elucidate the effects of PCDH10 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, we performed RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses and further validated the results by WB. Compared to control group, PCDH10-restorated T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells exhibited significantly reduced levels of dephosphorylated (active) β-catenin and increased levels of phosphorylated β-catenin (inactive form targeted for degradation) (Fig. 5A, Fig. S4A). Dephosphorylated β-catenin primarily functions as a transcriptional co-activator in the nucleus. These findings support the hypothesis that PCDH10 inhibits the activation/stabilization of β-catenin. GSK-3β phosphorylation at Ser9 inhibits its kinase activity, stabilizing β-catenin, whereas phosphorylation at Tyr216 is required for its activity, promoting β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation. Our results showed that PCDH10 differentially regulated GSK-3β phosphorylation at these key sites to promote its activity. In PCDH10-overexpressing T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, phosphorylation at the inhibitory Ser9 site was reduced, while phosphorylation at the activating Tyr216 site was upregulated. This combination enhances GSK-3β kinase activity, thereby promoting β-catenin degradation (Fig. 5A, Fig. S4A). Conversely, in ZR-75-1 cells with PCDH10 knockdown, phosphorylation at Tyr216 was reduced, and phosphorylation at Ser9 was increased. This dual change further suppresses GSK-3β activity, leading to the accumulation and activation of β-catenin (Fig. 5B).

Additionally, expression of MMP7, a downstream target gene of β-catenin, was examined to further confirm the inhibitory effects of PCDH10 on the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. WB analysis revealed that PCDH10 downregulated MMP7 expression in T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4B). PCDH10 also downregulated the levels of p-AKT and p-RhoA (Fig. 5C and Fig. S4B), both are known regulators of GSK-3β activity and β-catenin stability. Thus, PCDH10 may inhibit β-catenin activity partially by suppressing these signaling molecules.

To further validate the inhibitory effects of PCDH10 on Wnt/β-catenin pathway, we employed a TOP-Flash/FOP-Flash TCF luciferase reporter assay. Luciferase activity was significantly reduced in cells expressing PCDH10, including 293T, T-47D, and MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 5D). Treatment with Wnt/β-catenin signaling activator BML-284 in cells expression PCDH10 further confirmed its inhibitory effects (Fig. 5E, Fig. S4C). Finally, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by immunoblotting (IB) analyses confirmed direct protein-protein interactions among PCDH10, GSK-3β, and β-catenin (Fig. 5F, Fig. S4D). These results demonstrated that PCDH10 negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling through the GSK-3β/β-catenin axis via protein-protein interactions.

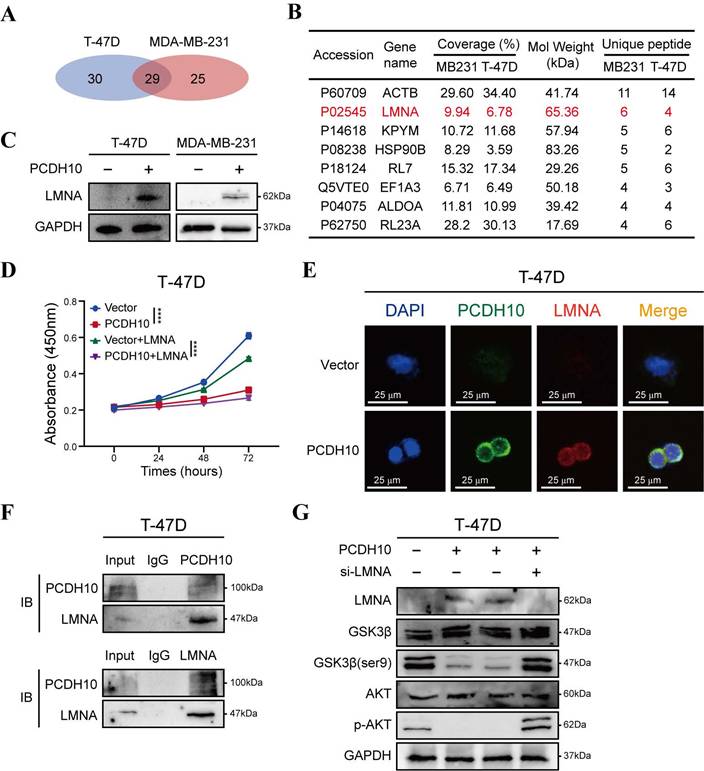

PCDH10 upregulates LMNA expression through Akt signal pathway

To further elucidate the tumor-suppressive mechanisms of PCDH10 in breast cancer, we employed co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) to identify PCDH10-interacting proteins, followed by mass spectrometry (MS) for protein identification. Silver staining of SDS-PAGE gels was used to visualize potential binding partners (Fig. S5A). Among 29 candidate binding proteins identified in PCDH10-expressing T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 6A), we selected LMNA (Lamin A/C) for further investigation based on our experimental results (Fig. 6B). LMNA is a major component of the nuclear lamina, responsible for maintaining nuclear structure and function, and plays a crucial role in cell differentiation, gene regulation and cell cycle control.

Our results demonstrated that PCDH10 expression upregulated LMNA expression (Fig. 6C). Additionally, functional assays revealed that LMNA mediated the growth-inhibitory effects of PCDH10 (Fig. 6D, Fig. S5B). IF analysis further confirmed the co-localization of PCDH10 and LMNA in T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 6E, Fig. S5C). Co-IP experiments showed direct protein-protein interaction between LMNA and PCDH10 (Fig. 6F, Fig. S5D).

Given the regulatory role of PCDH10 in Akt/β-catenin signaling, we explored the impact of LMNA on the Akt pathway. Previous results indicated that PCDH10 expression inhibits Akt signaling (Fig. 5C, Fig. S4B). In PCDH10-expressing T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, knockdown of LMNA partially restored p-Akt levels and increased p-GSK3β-Ser9, indicating LMNA mediates PCDH10's inhibition of Akt signaling (Fig. 6G, Fig. S5E). Thus, PCDH10 upregulates LMNA expression through protein-protein interactions, leading to inhibition of Akt signaling (via reduced p-Akt) and enhancement of GSK3β activity (via reduced p-Ser9) which can explain its anti-tumor effects.

Discussion

Carcinogenesis is a multi-step process that involves the accumulation of multiple epigenetic and genetic alterations of oncogenes and TSGs [3]. Reprograming the epigenetic landscape of the cancer genome is a promising therapeutic strategy [29]. TSG methylation contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple cancers, including breast cancer [30, 31]. The regulatory mechanism underlying the methylation system comprises several components: DNA methyltransferases and methyl-CpG binding proteins (MeCPs). DNA methyltransferases, including DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B (and DNMT2, though its primary role is debated [32]), are involved in establishing and maintaining methylation patterns [33]. MeCPs recognize methylated CpG sites. Key MeCPs members such as MeCP2, MBD1, MBD2 and MBD4 contain methylated DNA-binding domains (MBDs) [34]. Additionally, histone modifications interact closely with DNA methylation in gene silencing [35].

We discovered the downregulation or silencing of PCDH10 in most breast cancer tissues and cell lines tested. Methylation analysis and demethylation treatment indicated that the principal regulatory mechanism underlying PCDH10 inactivation is aberrant promoter CpG methylation. RT-PCR also detected unmethylated alleles in YCC-B3 and SK-BR-3, suggesting that other repression regulatory mechanisms, such as histone modifications [36] might also contribute to its silencing. CpG methylation, which leads to the loss of TSG function, is closely associated with the onset and progression of multiple types of cancers [4]. We observed PCDH10 methylation in 83% of primary breast tumor tissues, whereas no PCDH10 methylation was observed in adjacent non-tumor tissues. These results suggested that aberrant promoter methylation of PCDH10 occurs early in the multistep process of breast carcinogenesis. Notably, PCDH10 methylation is documented in other primary tumors, including esophageal [17], gastric [36], cervical [14] and hepatocellular cancers [37], reinforcing its broad tumor-suppressive role. While its timing relative to tumor grade or stage warrants further study, future work should validate PCDH10 methylation in serum or tumor tissues as a diagnostic/screening biomarker.

This study establishes PCDH10 methylation as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer, with higher expression correlating with significantly longer patient survival and ER-positive status. The tumor-suppressive effects of PCDH10 in breast cancer cells were determined using CCK8, wound healing, Transwell®, cell cycle, apoptosis, and cell spheroid formation assays in vitro, as well as subcutaneous tumor model in vivo. WB results further confirmed that PCDH10 inhibited tumor cells growth, EMT and stemness. PCDH10 also promoted G0/G1 phase arrest and apoptosis. Collectively, PCDH10 restoration coordinately suppresses breast cancer growth, metastasis, and stem-like properties, highlighting its therapeutic potential.

PCDH10 expression antagonizes aberrant oncogenic β-catenin activation, likely through protein-protein interaction. A-B Western blot analysis of GSK-3β and β-catenin status in vector versus PCDH10-OE of T-47D (A), or shNC versus shPCDH10 of ZR-75-1 (B). C Western blot analysis of MMP7, p-RhoA, and p-AKT in vector versus PCDH10-OE of T-47D. D PCDH10 effect on TOPFLASH TCF-reporter construct activity was determined in T-47D, MDA-MB-231 and 293T (n = 24). E CCK8 was applied to detect inhibitive effect of PCDH10 on Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and BML-284 was applied to activate β-catenin signaling in T-47D (n=3, two-way ANOVA). F Co-IP isolated extracts were applied for IB to confirm binding of PCDH10, GSK-3β and β-catenin in 293T and T-47D. Data are presented as mean ± SD; Each dot represents one sample. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.****p < 0.0001. IB: Immunoblot.

PCDH10 upregulates LMNA expression through protein-protein interaction. A Workflow of IP screening. B Distinct protein bands in the GEL were subjected to mass spectrometry, and the top eight interacting partners are shown. C Western blot analysis of LMNA in vector versus PCDH10-OE T-47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. D CCK8 determining LMNA effect on tumor cells growth in vector versus PCDH10-OE T-47D cells (n=3, two-way ANOVA). E IF staining showed representative images of PCDH10 (green) and LMNA (red) in vector versus PCDH10-OE T-47D cells. F IB and Co-IP performing to confirm protein-protein combination in T-47D. G Western blot analysis of LMNA, GSK-3β, GSK-3β (ser9), p-AKT and AKT in vector versus PCDH10-OE T-47D cells. IB: Immunoblot; WB: Western Blot. ****p < 0.0001.

EMT, the process whereby epithelial cells transdifferentiate into motile mesenchymal cells, is critical for metastatic progression in breast cancer. In our study, restoration of PCDH10 significantly inhibited the expression of EMT and stemness markers in breast cancer cells, including N-cadherin, Vimentin, Slug, among others. RNA-seq KEGG analysis revealed enrichment in Wnt signaling pathway, focal adhesion, cell adhesion molecules, and others. Mechanistically, PCDH10 downregulated Wnt/β-catenin target genes Axin2 and cyclin D1 [38]. Furthermore, PCDH10 downregulated multiple β-catenin/TCF-LEF transcriptionally regulated genes and related oncogenes, including WNT5B, HIF1A, VEGFA, VEGFC and EGFR. WNT5B [39] is closely related to Wnt/β-catenin pathway and have been reported to promote the metastatic ability of cancer cells. HIF1A exerts tumor-promoted effects through regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling [26]. VEGFA and VEGFC [27] are also regulated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Convergence exists between Wnt/β-catenin and EGFR signaling [28]. These results confirmed the tumor-suppressive function of PCDH10 through potent inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

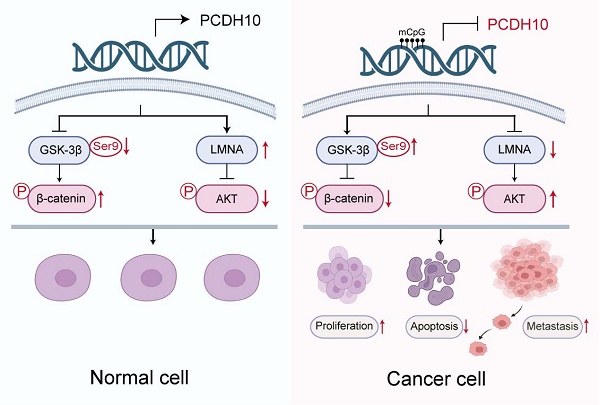

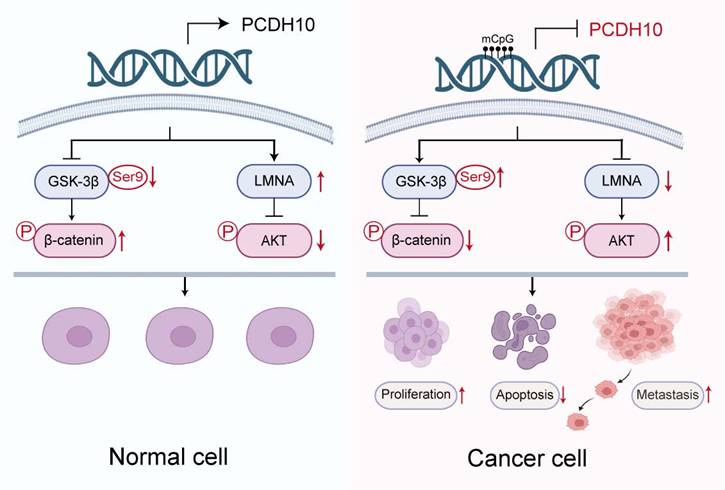

Schematic illustration of the tumor-suppressive mechanism of PCDH10 in breast cancer. In breast cancer cells, promoter methylation silences PCDH10, resulting in increased GSK-3β (Ser9) phosphorylation, decreased β-catenin phosphorylation, downregulation of LMNA, and activation of Akt signaling. These changes collectively promote tumor cell proliferation, inhibit apoptosis, and enhance metastasis.

Protocadherins mediate cell sorting, selective cell-cell adhesion, and homophilic binding [40]. Although we demonstrate PCDH10 is predominantly located in the cytoplasm, the functions of protocadherins can change during carcinogenesis, and they can act as signaling molecules that participates in regulating signaling pathways [41].

WNTs are glycoproteins secreted into the extracellular matrix. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway features “Wnt on” and “Wnt off” states; the presence of WNT ligands “turn on” the pathway by promoting the accumulation of active β-catenin through inactivation of GSK-3β [42]. GSK-3β, which forms a complex with CK1α and APC to target β-catenin for phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation [43]. We demonstrate that PCDH10 enhances the active form of GSK-3β, suppressing β-catenin stabilization. Consistently, PCDH10 overexpression significantly reduced TOPFLASH reporter activity. Since TCF/Lef1 (T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor-1) mediates canonical WNT-triggered gene transcription, this supports the finding that PCDH10 antagonized Wnt/β-catenin signaling by downregulating active β-catenin levels. Additionally, PCDH10 suppressed MMP7 expression, a β-catenin downstream target gene. Furthermore, PCDH10 suppressed p-AKT and p-RhoA expression, which are critical regulators of β-catenin [44]. Critically, co-immunoprecipitation verified direct binding between PCDH10, GSK-3β and β-catenin, establishing PCDH10 as a scaffold protein that orchestrates β-catenin degradation through GSK-3β activation while concurrently inhibiting AKT/RhoA-mediated β-catenin stabilization. Future studies employing specific pathway modulators (e.g., Wnt activators/inhibitors, PI3K/Akt inhibitors) will be valuable to further delineate the pathway dependencies and consolidate these mechanistic insights.

We further established that LMNA, a nuclear intermediate filament, directly interacts with PCDH10. PCDH10 overexpression significantly increased LMNA protein levels in breast cancer cells. Notably, LMNA functions as a TSG in carcinomas [45], with its loss of expression correlating with poor prognosis and shorter survival in breast cancer patients [46]. Consistent with this role, our functional studies indicated that LMNA is a critical downstream mediator of PCDH10's tumor-suppressive function. Emerin, an inner nuclear membrane protein, requires LMNA for its proper localization [47] and interacts with β-catenin, restricting its nucleus access [48]. The upregulation of LMNA by PCDH10 might inhibit β-catenin activity by promoting emerin-mediated sequestration, though this model requires further experimental validation.

In summary, this study reveals frequent epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor PCDH10 in breast cancer, which correlates with ER-positive status and longer patient survival. Mechanistic analyses indicated that PCDH10 antagonizes Wnt/β-catenin signaling through its interaction with GSK-3β/β-catenin complex as a scaffold protein and via LMNA upregulation. PCDH10 additionally suppresses AKT and RhoA phosphorylation (Fig. 7). The frequent aberrant epigenetic silencing event likely plays an essential role in breast cancer carcinogenesis, also positioning PCDH10 methylation as a promising diagnostic or prognostic biomarker.

Materials and Methods

Tumor samples, normal tissues and cell lines

RNA samples from human normal adult breast tissue were commercially obtained (BioChain Institute, Hayward, CA and Millipore Chemicon, Billerica, MA; or Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Primary Breast carcinoma, adjacent non-cancerous tissues, and normal breast tissues were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (CQMU) as previously described [9, 49]. Breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, T-47D, MCF7, BT549, MDA-MB-468, SK-BR-3, ZR-75-1, YCCB1, and YCCB3) and 293T were used. Cells were obtained from collaborators or purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were routinely maintained in DMEM or RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco).

DNA and RNA extraction

Total RNA and DNA were extracted from tissues and cells using TRIzol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For DNA extraction from normal and breast tumor tissues, samples were homogenized using liquid nitrogen and incubated in a solution containing 200 µg/ml proteinase K, 50 mM EDTA, 2% N-lauryl-sarcosyl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 10 mM NaCl for 20 h at 55ºC. The samples were then extracted with phenol-chloroform extraction and subjected to ethanol precipitation. For RNA-seq analysis, cells were lysed with TRIzol® Reagent, and data analysis were performed by LC Sciences (Hangzhou, China).

Promoter methylation analysis and bisulfite treatment

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP) [49], bisulfite modification of DNA, and BGS [50] were performed as described previously. The MSP primers had been tested previously, and direct sequencing was used to analyze the MSP products to confirm that the MSP system was specific. Primers used were listed in Supplementary table 1. For BGS, the following primers were used to amplify bisulfite-treated DNA: BGS1: 5′- GTT GAT GTA AAT AGG GGA ATT-3′ and BGS2: 5′-CTT CAA CCT CTA AAC CTA TAA-3′. The PCR products were cloned into the PCR4-Topo vector (Invitrogen). Randomly selected 8-10 colonies were applied for further sequencing.

5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine (Aza) and Trichostatin A (TSA) treatment

The demethylating agent Aza (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and the histone deacetylase inhibitor TSA (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI, USA) were used. For Aza and TSA treatment, cells were treated with Aza (10 µM, Sigma) for 3 days followed by TSA (100 ng/mL) for 1 day.

Cloning PCDH10 and constructing the expression vector

AccuPrime Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and a full-length clone of KIAA1400 (a kind gift from Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Chiba, Japan) were used to generate the PCR product and to construct the pcDNA3.1(+)-PCDH10 plasmid. Sequencing was used to confirm all construct sequences and orientations.

Construction of cells with stable PCDH10 expression

MDA-MB-231 and T-47D were chosen to establish cell lines stably expressing PCDH10. Following the manufacturer's instructions, cells were transfected with the PCDH10 plasmid using Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). Transfected MDA-MB-231 and T-47D were cultured for additional 48 hours and then selected with G418. The cell cultures used are mixed cultures of stable transfectants. WB were applied to confirm PCDH10 ectopic expression.

Reverse transcription-PCR, semi-quantitative (RT)-PCR and qRT-PCR

Reverse transcription of RNA was performed with GoScriptTM reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI), and reaction conditions were as previously reported. AmpliTaq Gold T (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to perform Semi-quantitative (RT)-PCR as previously reported. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Based on the instrument manual (HT7500 System; Applied Biosystems, Foster), qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Green (Promega). The 2-∆Ct method was used to calculat relative expression. GAPDH was amplified as a control for RNA integrity.

Proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assayed using the CCK-8 (Cell Counting Kit-8, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) at 0, 24, 48 and 72 hours. In the 96-well plates, breast cancer cells with or without ectopic expression of PCDH10 were seeded (2000 cells per well). A microplate reader was used to examine the absorbance at 450 nm (TECAN, Infinite M200 Pro).

Agents

To detect sensitivity to doxorubicin (DOXO), cells were treated with DOXO (Abcam, ab120629) at 1 μg/mL for 24 hours, and then subjected to the proliferation assay. To investigate the inhibitory effect of PCDH10 on Wnt/β-catenin signaling, cells were treated with 10 μM BML-284 (MCE, HY-19987) for 24 hours. Treated cells were then analyzed using the CCK-8 assay. Vector-transfected cells and DMSO-treated cells were used as controls.

Colony formation assay

Cells expressing PCDH10 or an empty vector, along with wild-type breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, 800 cells/well; T-47D, 1200 cells/well) were seeded in 6-well plates. Untransfected breast cancer cells were eliminated by G418 selection. Surviving colonies were counted (>50 cells/colony).

Cell cycle and apoptosis analyses

Flow cytometry (FC) analysis was performed to assess apoptosis and cell cycle distribution. Cells (10 × 105) were cultured in 6-well plates for 48 hours and subsequently harvested. Cells were processed as previously described [49]. Cell cycle distribution and apoptosis were analyzed using a BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer; cell cycle data were analyzed using ModFit LT software and apoptosis data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Wound healing assays

The scratch wound assay was used to assess cell mobility in 6-well plates. Empty vector-transfected and PCDH10-expressing cells were cultured until confluent. Cells were washed with PBS and then cultured in serum-free RPMI-1640. After scratching the monolayer, images were acquired using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and wound widths were measured.

Transwell® assay

The invasive or migratory abilities of breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231, 1 × 104 cells/well, 48 hours; T-47D, 2×104 cells/well, 72 hours) were determined using Transwell® plates coated with or without Matrigel (C0371, beyotime). Breast cancer cells were starved overnight and processed as described previously [31].

Cell spheroid formation assay

Spheroid-forming assays were performed using PCDH10 stably-expressing breast cancer cells as described previously [49]. Vector-transfected cells were used as controls. Following continuous culture until distinct, compact tumor spheroids formed (containing > 50 cells per spheroid), the spheroids were visualized under an inverted phase-contrast microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and subsequently counted.

In vivo tumor model

Ten female nude mice were obtained commercially from Enswell Biotechnology Co., Ltd, China. Mice were randomly divided into two groups, and subcutaneously injected with MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106 cells) stably expressing empty-vector or PCDH10. Body weight and tumor size were measured and recorded every 3 days. Mice were euthanized before the volume of any tumor reached 1 cm3. Excised tumors were photographed and fixed in formalin for paraffin embedding.

IF and IHC

MDA-MB-231 and T-47D cells were transfected with empty vector or PCDH10 plasmid. Transfected cells were cultured on glass coverslips in 6-well plates. After washing three times with PBS, samples were processed as previously reported [9]. The primary antibodies used were as follows: E-cadherin (sc-21791, Santa Cruz, 1:100), LMNA (HA601274, HUABIO, 1:100), and PCDH10 (21859-1-AP, proteintech, 1:50). DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain. Anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor®488 (ab150077, Abcam, 1:200) and anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor® 594 (ab150116, Abcam, 1:200) were applied as secondary antibodies. Co-localization analysis was performed using using LAS AF software (Leica confocal microscope). For IHC, human patient and mouse samples were analyzed following a previously published protocol [51]. The antibody used for detection was anti-PCDH10 (21859-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:200), E-cadherin (EM0502, HUABIO, 1:500), and N-cadherin (ET1607-37, HUABIO, 1:200).

Western blot (WB) and Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

For WB, cells were lysed in ice-cold PBS containing 1 mM PMSF (Thermo Fisher) and cocktail (Thermo Fisher). Protein lysates were mixed with loading buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE as previously described [52]. Membranes were incubated with the indicated monoclonal antibodies, including PCDH10 (21859-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:1000), PCNA (EM111201, HUABIO, 1:1000), CyclinD1 (ER0722, HUABIO, 1:1000), P27 (ET1608-61, HUABIO, 1:1000), PARP (9532, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), Cleaved-PARP (HA722218, HUABIO, 1:1000), Cleaved-casp3 (25128-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:1000), N-cadherin (ET1607-37, HUABIO, 1:1000), Vimentin (ET1610-39, HUABIO, 1:1000), E-cadherin (ET1607-75, HUABIO, 1:1000), Slug (9585, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), β-catenin (8480, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), non-phospho (Active) β-catenin (8814, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), p-β-catenin (HA721580, HUABIO, 1:1000), GSK-3β (ET1607-71, HUABIO, 1:1000), p-GSK-3β ser9 (ET1607-60, HUABIO, 1:1000), p-GSK-3β try216 (ET1607-54, HUABIO, 1:1000), LMNA (ET7110-12, HUABIO, 1:1000), AKT (10176-2-AP, Proteintech, 1:1000), p-AKT (4060, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), MMP7 (ab207299, Abcam, 1:1000), RhoA (ET1611-10, HUABIO, 1:1000), p-RhoA (AF3352, Affinity, 1:1000), β-tubulin (2146, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), GAPDH (2118, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000). Membranes were washed three times with PBST, then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Biosharp, 1:2000) or anti-mouse IgG (Biosharp, 1:2000). Signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) on a Gel Imager System (FX5, Vilber Lourmat).

For Co-IP, Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (HY-K0202, MCE) were used according to a published protocol (ref. 60). Lysates were incubated with antibodies against: Flag tag (DYKDDDDK, #14793, CST, 1:50), GSK-3β (sc-377213, Santa Cruz, 1:50), β-catenin (sc-65480, Santa Cruz, 1:50), and LMNA (sc-376248, Santa Cruz, 1:50). Co-IP complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and WB. For detection, anti-mouse IgG (#A25012, Abbkine, 1:3000) was used. IP efficiency was confirmed by silver staining (P0017S, Beyotime). Entire gel lanes were excised for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis (Wuhan GeneCreate Biological Engineering Co., Ltd.).

Luciferase activity assay

Cells were co-transfected with TOPFLASH (TCF reporter) and Renilla luciferase (internal control) constructs, along with empty vector or PCDH10, using Lipofectamine 3000. Cells were harvested 48 hours post-transfection. Lysates were transferred to a 96-well OptiPlate™, and luciferase activity was measured (TECAN Infinite M200 Pro). Firefly luciferase activity (TOPFLASH) was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Measurements were performed in triplicate [53].

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

PCDH10 methylation in breast cancer was analyzed using the MethHC database. The results are presented as mean ± SD. Functional analysis, qRT-PCR, WB, and other assays were performed at least three times. Patient characteristics and methylation status were obtained from TCGA. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and GENT2 expression data accessed online. GraphPad Prism (version 8.0) was used for statistical analyses. For RNA-seq analysis, total RNA was extracted from MDA-MB-231 cells using Trizol reagent. Sequencing libraries were prepared and sequenced on the NovaSeq platform by LC-Bio Technologies (Hangzhou) Co., Ltd. Pathway enrichment was analyzed using the KEGG database with R clusterProfiler (v4.1.0), and GSEA (v4.0.3) was applied for further analysis. Statistical comparisons were conducted using t-test, two-way ANOVA, and log-rank test. p values <0.05 were considered to represent a statistically significant difference. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

Abbreviations

CCK8: cell counting kit-8; BGS: bisulfite genomic sequencing; DOXO: doxorubicin; Co-IP: co-immunoprecipitation; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; FC: flow cytometry; CGI: CpG islands; IB: immunoblot; IF: immunofluorescence; IHC: immunohistochemistry; MS: mass spectrum; MSP: methylation-specific PCR; RNA-seq: RNA sequencing; TSG: tumor suppressor gene; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; WB: western blot.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and table.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82173166, 82573162, and 31420103915), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTB2025NSCQ-LZX0151), Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (14111924), and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation-Hong Kong joint grant (2024SQGH005517).

Author contributions

QT, GR, HL: Conceptualization and Supervision. XW, YT, YW, YC: Investigation. X W: original draft. TX, and LL: Methodology and acquire data work. WP, ZQ: Resources. QT, HL, XW: edit and finalize the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published articles and its additional information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was authorized by Institutional Ethics Committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (#2020-427) and abided by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Jan-Feb;74(1):12-49

2. Wagle NS, Nogueira L, Devasia TP. et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025 Jul-Aug;75(4):308-340

3. Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer - a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction? Nat Rev Cancer. 2006Feb;6(2):107-16

4. Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002Jun;3(6):415-28

5. Li L, Fan Y, Huang X. et al. Tumor Suppression of Ras GTPase-Activating Protein RASA5 through Antagonizing Ras Signaling Perturbation in Carcinomas. iScience. 2019Nov22;21:1-18

6. Pineda B, Diaz-Lagares A, Pérez-Fidalgo JA. et al. A two-gene epigenetic signature for the prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Clin Epigenetics. 2019Feb20;11(1):33

7. Li L, Xu J, Qiu G. et al. Epigenomic characterization of a p53-regulated 3p22.2 tumor suppressor that inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation via protein docking and is frequently methylated in esophageal and other carcinomas. Theranostics. 2018Jan1;8(1):61-77 doi: 10.7150/thno.20893

8. Li M, Wang C, Yu B. et al. Diagnostic value of RASSF1A methylation for breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 2019Jun28;39(6):BSR20190923

9. Le X, Mu J, Peng W. et al. DNA methylation downregulated ZDHHC1 suppresses tumor growth by altering cellular metabolism and inducing oxidative/ER stress-mediated apoptosis and pyroptosis. Theranostics. 2020Jul25;10(21):9495-9511

10. Yagi T. Clustered protocadherin family. Dev Growth Differ. 2008Jun;50(Suppl 1):S131-40

11. Shapiro L, Fannon AM, Kwong PD. et al. Structural basis of cell-cell adhesion by cadherins. Nature. 1995Mar23;374(6520):327-37

12. Wolverton T, Lalande M. Identification and characterization of three members of a novel subclass of protocadherins. Genomics. 2001Aug;76(1-3):66-72

13. Yu J, Cheng YY, Tao Q. et al. Methylation of protocadherin 10, a novel tumor suppressor, is associated with poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009Feb;136(2):640-51.e1

14. Narayan G, Scotto L, Neelakantan V. et al. Protocadherin PCDH10, involved in tumor progression, is a frequent and early target of promoter hypermethylation in cervical cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009Nov;48(11):983-92

15. Jao TM, Fang WH, Ciou SC. et al. PCDH10 exerts tumor-suppressor functions through modulation of EGFR/AKT axis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021Feb28;499:290-300

16. Ye M, Li J, Gong J. PCDH10 gene inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2017Jun;37(6):3167-3174

17. Ying J, Li H, Seng TJ. et al. Functional epigenetics identifies a protocadherin PCDH10 as a candidate tumor suppressor for nasopharyngeal, esophageal and multiple other carcinomas with frequent methylation. Oncogene. 2006Feb16;25(7):1070-80

18. Liu W, Wu J, Shi G. et al. Aberrant promoter methylation of PCDH10 as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for patients with breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018Oct;16(4):4462-4470

19. Juríková M, Danihel Ľ, Polák Š. et al. Ki67, PCNA, and MCM proteins: Markers of proliferation in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Acta Histochem. 2016Jun;118(5):544-52

20. Wang ST, Ho HJ, Lin JT. et al. Simvastatin-induced cell cycle arrest through inhibition of STAT3/SKP2 axis and activation of AMPK to promote p27 and p21 accumulation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017Feb23;8(2):e2626

21. Nagaraja SS, Nagarajan D. Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: A Review on Targeting Molecular Pathways and Mediators. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19(10):1191-1204

22. Papadaki MA, Stoupis G, Theodoropoulos PA. et al. Circulating Tumor Cells with Stemness and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Features Are Chemoresistant and Predictive of Poor Outcome in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019Feb;18(2):437-447

23. Gong Z, Hu G. PCDH20 acts as a tumour-suppressor gene through the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2019;26(2):209-217

24. Yin X, Xiang T, Mu J. et al. Protocadherin 17 functions as a tumor suppressor suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling and cell metastasis and is frequently methylated in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016Aug9;7(32):51720-51732

25. Zhang Q, Fan H, Liu H. et al. WNT5B exerts oncogenic effects and is negatively regulated by miR-5587-3p in lung adenocarcinoma progression. Oncogene. 2020Feb;39(7):1484-1497

26. Jiang N, Zou C, Zhu Y. et al. HIF-1ɑ-regulated miR-1275 maintains stem cell-like phenotypes and promotes the progression of LUAD by simultaneously activating Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling. Theranostics. 2020Jan22;10(6):2553-2570

27. Gore AV, Swift MR, Cha YR. et al. Rspo1/Wnt signaling promotes angiogenesis via Vegfc/Vegfr3. Development. 2011Nov;138(22):4875-86

28. Hu T, Li C. Convergence between Wnt-β-catenin and EGFR signaling in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010Sep9;9:236

29. Miranda Furtado CL, Dos Santos Luciano MC, Silva Santos RD. et al. Epidrugs: targeting epigenetic marks in cancer treatment. Epigenetics. 2019Dec;14(12):1164-1176

30. Feng Y, Wu M, Li S. et al. The epigenetically downregulated factor CYGB suppresses breast cancer through inhibition of glucose metabolism. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018Dec13;37(1):313

31. Shao B, Feng Y, Zhang H. et al. The 3p14.2 tumour suppressor ADAMTS9 is inactivated by promoter CpG methylation and inhibits tumour cell growth in breast cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2018Feb;22(2):1257-1271

32. Li H, Liu H, Zhu D. et al. Biological function molecular pathways and druggability of DNMT2/TRDMT1. Pharmacol Res. 2024Jul;205:107222

33. Man X, Li Q, Wang B. et al. DNMT3A and DNMT3B in Breast Tumorigenesis and Potential Therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022May10;10:916725

34. Du Q, Luu PL, Stirzaker C. et al. Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins: readers of the epigenome. Epigenomics. 2015;7(6):1051-73

35. Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009May;10(5):295-304

36. Yu B, Yang H, Zhang C. et al. High-resolution melting analysis of PCDH10 methylation levels in gastric, colorectal and pancreatic cancers. Neoplasma. 2010;57(3):247-52

37. Fang S, Huang SF, Cao J. et al. Silencing of PCDH10 in hepatocellular carcinoma via de novo DNA methylation independent of HBV infection or HBX expression. Clin Exp Med. 2013May;13(2):127-34

38. Li Y, Jin K, van Pelt GW, van Dam H. et al. c-Myb Enhances Breast Cancer Invasion and Metastasis through the Wnt/β-Catenin/Axin2 Pathway. Cancer Res. 2016Jun1;76(11):3364-75

39. Harada T, Yamamoto H, Kishida S. et al. Wnt5b-associated exosomes promote cancer cell migration and proliferation. Cancer Sci. 2017Jan;108(1):42-52

40. Hirayama T, Yagi T. Clustered protocadherins and neuronal diversity. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2013;116:145-67

41. Medina A, Swain RK, Kuerner KM. et al. Xenopus paraxial protocadherin has signaling functions and is involved in tissue separation. EMBO J. 2004Aug18;23(16):3249-58

42. Pai SG, Carneiro BA, Mota JM. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. J Hematol Oncol. 2017May5;10(1):101

43. Krishnamurthy N, Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: Update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018Jan;62:50-60

44. Kim JG, Islam R, Cho JY. et al. Regulation of RhoA GTPase and various transcription factors in the RhoA pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2018Sep;233(9):6381-6392

45. Antmen E, Demirci U, Hasirci V. Amplification of nuclear deformation of breast cancer cells by seeding on micropatterned surfaces to better distinguish their malignancies. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019Nov1;183:110402

46. Zuo L, Zhao H, Yang R. et al. Lamin A/C might be involved in the EMT signalling pathway. Gene. 2018Jul15;663:51-64

47. Alhudiri IM, Nolan CC, Ellis IO. et al. Expression of Lamin A/C in early-stage breast cancer and its prognostic value. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019Apr;174(3):661-668

48. Ho CY, Jaalouk DE, Vartiainen MK. et al. Lamin A/C and emerin regulate MKL1-SRF activity by modulating actin dynamics. Nature. 2013May23;497(7450):507-11

49. Xiang T, Tang J, Li L. et al. Tumor suppressive BTB/POZ zinc-finger protein ZBTB28 inhibits oncogenic BCL6/ZBTB27 signaling to maintain p53 transcription in multiple carcinogenesis. Theranostics. 2019Oct18;9(26):8182-8195

50. Fan J, Zhang Y, Mu J. et al. TET1 exerts its anti-tumor functions via demethylating DACT2 and SFRP2 to antagonize Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Clin Epigenetics. 2018Aug3;10(1):103

51. Sun R, Xiang T, Tang J. et al. 19q13 KRAB zinc-finger protein ZNF471 activates MAPK10/JNK3 signaling but is frequently silenced by promoter CpG methylation in esophageal cancer. Theranostics. 2020Jan12;10(5):2243-2259

52. Li L, Tao Q, Jin H. et al. The tumor suppressor UCHL1 forms a complex with p53/MDM2/ARF to promote p53 signaling and is frequently silenced in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010Jun1;16(11):2949-58

53. Zhang C, Xiang T, Li S. et al. The novel 19q13 KRAB zinc-finger tumour suppressor ZNF382 is frequently methylated in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and antagonises Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Cell Death Dis. 2018May1;9(5):573

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Qian Tao, E-mail: qtaoedu.hk, Guosheng Ren, E-mail: rengs726com, Hongzhong Li, E-mail: lihongzhongedu.cn.

Corresponding authors: Qian Tao, E-mail: qtaoedu.hk, Guosheng Ren, E-mail: rengs726com, Hongzhong Li, E-mail: lihongzhongedu.cn.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact