Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(5):2383-2397. doi:10.7150/ijbs.123725 This issue Cite

Research Paper

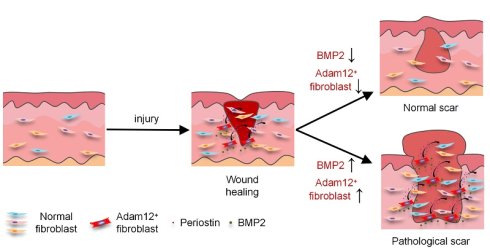

BMP2-induced Adam12+ Fibroblasts Dictate Wound-associated Skin Scarring and Fibrosis

1. Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China.

2. The First School of Clinical Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China.

3. Cancer Research Institute, School of Basic Medical Sciences, State Key Laboratory of Organ Failure Research, National Clinical Research Center of Kidney Disease, Key Laboratory of Organ Failure Research (Ministry of Education), Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China.

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-8-14; Accepted 2026-1-22; Published 2026-2-4

Abstract

Skin wounds typically undergo healing through scar formation, a fibrotic process mainly mediated by fibroblasts. Cumulative evidence from our group and others has established that Adam12+ fibroblasts were upregulated following skin injury and played a crucial role in scar formation. However, the molecular mechanisms governing the origin and pathogenesis of Adam12+ fibroblasts during skin scarring remain elusive. Here, we demonstrated that Adam12+ fibroblasts were necessary for wound-associated skin scarring and fibrosis. We identified BMP2 as the essential upstream signal for the generation of Adam12+ fibroblasts from resident fibroblasts and periostin as the key downstream effectors. Fibroblast-specific conditional knockout of BMP2 receptor significantly reduced Adam12+ fibroblast population, periostin expression, and ultimately skin scarring and fibrosis post-injury. BMP2, periostin and Adam12+ fibroblasts were found to be increased significantly in pathological scars compared with normal scars, and augmentation of BMP2 signaling expanded Adam12+ fibroblast population and exacerbated skin scarring and fibrosis, suggesting that BMP2 overexpression may contribute to pathological scarring. Pharmacological inhibition of BMP2 signaling markedly attenuated pathological scars. Taken together, our findings will help to understand skin fibrosis pathogenesis and provide potential targets for the therapy of pathological scars.

Keywords: BMP2, fibroblast, wound, scar, fibrosis

Introduction

Skin wounds generally heal by scarring, a fibrotic process mainly mediated by fibroblasts[1-3]. In some situations, skin injury will lead to pathological scars, such as hypertrophic scar or keloid[1, 4, 5]. The global impact of pathological scars is significant, which affects millions of people worldwide[4-6]. Multiple factors have been reported to play important roles in the pathogenesis of pathological scars, including genetic factors, epigenetic factors, dysregulated fibrotic signaling, inflammatory dysregulation, extracellular matrix imbalance and mechanical stress[5, 7, 8]. To date, the pathogenesis of pathological scars has not been thoroughly elucidated, and curative treatments are still lacking.

Fibroblasts are the predominant cell type that synthesizes and remodels the extracellular matrix in the process of scarring after skin injury[1, 2, 5]. Emerging consensus indicates that wound-associated fibroblasts exhibit remarkable spatial, molecular and functional heterogeneity[1, 9, 10]. Fibroblasts from different embryonic origins may influence their fibrotic behavior in postnatal life: neural crest-derived, Wnt1 lineage-positive fibroblasts mediate scarless healing of the oral mucosa, while scar healing in the skin of the trunk is accomplished by paraxial mesoderm-derived, Engrailed-1 lineage-positive fibroblasts in the dorsal skin[1, 11], and lateral plate mesoderm-derived, paired related homeobox 1 (Prrx1) lineage-positive fibroblasts in the ventral skin[1, 12]. Skin fibroblasts have also been differentiated into papillary, reticular, and hypodermal subpopulations based on lineage, surface marker expression, and location within the dermis. Papillary fibroblasts (CD26+Lrig+Sca1-) descended from Blimp1 lineage-positive, Dlk1-Lrig+ progenitors are closely associated with the overlying epithelium, but reticular (Dlk1+Sca1-) and hypodermal (CD24+Dlk1-Sca1+) fibroblasts reside deeper within the dermis and contribute to the vast majority of early fibrosis during wound healing[9, 13].

Our recent single-cell RNA sequencing study revealed four functionally distinct fibroblast subpopulations in keloid tissue: mesenchymal, secretory-papillary, secretory-reticular and pro-inflammatory[14]. Mesenchymal fibroblasts expressed genes associated with skeletal system development, ossification, and osteoblast differentiation, such as ADAM12, POSTN and RUNX2, suggesting a stronger mesenchymal component in this cell subpopulation. ADAM12+ mesenchymal fibroblast subpopulation was significantly increased in keloid compared with normal scar and crucial for collagen over-expression in keloid[14]. These data establish ADAM12+ fibroblasts as a clinically relevant driver of pathological scarring. However, the origin and pathogenesis of ADAM12+ fibroblasts in skin scarring are still elusive.

In this study, we used lineage tracing, cell ablation and conditional knockout technologies to explore the origin and pathogenesis of Adam12+ fibroblasts in skin scarring. Our results indicated that Adam12+ fibroblasts increased after skin injury and were necessary for wound-associated skin scarring and fibrosis. We identified BMP2 as the key cytokine for the generation of Adam12+ fibroblasts from unwound fibroblasts and periostin as the key effector for the function of Adam12+ fibroblasts. BMP2, periostin and Adam12+ fibroblasts were increased significantly in hypertrophic scar and keloid compared with normal scars and enhancing BMP2 signaling aggravated the degree of scarring after skin injury. Treatment of hypertrophic scar with BMP2 inhibitor significantly decreased the degree of scarring and fibrosis. These findings will help us understand skin scarring pathogenesis in depth, and provide potential targets for clinical therapies of skin fibrotic diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of South China Agricultural University (2023D105). Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at 20-26°C with 30-70% humidity. For the in vivo experiments, mice were age-matched and randomly assigned to experimental groups, using at least n=3 mice per genotype or treatment. C57BL/6J (WT) mice were purchased from Guangzhou Yancheng Biological Technology Co. Ltd (Guangzhou, China). Adam12-tdTomato mice and Adam12CreERT2 mice were constructed by Cyagen Company (Suzhou, China), in which the ATG start codon of Adam12 was replaced by Kozak-tdTomato-rBG pA or CreERT2-rBG pA. Postnfl/fl, Krt5CreERT2 and R26LSL-tdTomato mice were obtained from Cyagen Company (Suzhou, China). R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR, PdgfraCreERT2, Sm22CreERT2 and Bmpr2fl/fl mice were obtained from Shanghai Model Organisms Center (Shanghai, China).

For Adam12+ cells ablation experiments, Adam12CreERT2 mice were crossed with R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice to obtain Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice. The mice received 5x 100mg/kg bodyweight tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma) in corn oil/ethanol (9:1) via intraperitoneal injection at indicated time points relative to wounding to induce the expression of DTR in Adam12+ cells. These mice then received an intradermal injection (4x) of 50μL of 4ng/μl diphtheria toxin (DT) (D0564, Sigma) in PBS to deplete Adam12+ cells.

For Postn and Bmpr2 conditional knock-out experiments, Adam12CreERT2 and PdgfraCreERT2 mice were crossed with Postnfl/fl and Bmpr2fl/fl mice to get Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/fl and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice, respectively. The mice received 5x 100mg/kg body weight tamoxifen in corn oil/ethanol (9:1) via intraperitoneal injection at the indicated time points relative to wounding to induce the conditional knock-out of target genes.

For lineage tracing experiments, PdgfraCreERT2 mice, Krt5CreERT2 mice and Sm22CreERT2 mice were crossed with R26LSL-tdTomato mice to get PdgfraCreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato, Krt5CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato and Sm22CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice, respectively. The mice received 3x 100mg/kg body weight tamoxifen in corn oil/ethanol (9:1) via intraperitoneal injection to induce the expression of tdTomato in target cells in unwound skin. It is worth noting that the administration of tamoxifen was stopped 7 days before wounding to avoid tamoxifen interference in the results of lineage tracing.

Dorsal excisional wounding

Dorsal Excisional Wounding experiments were performed in accordance with well-established protocol[15]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized and their dorsal hair was removed with shaving devices. Then two 6 mm full-thickness circular wounds were placed through the panniculus carnosus on the dorsum of each animal at the same level by a punch. The wounds were then stented open by 14 mm diameter silicone rings secured around the wound perimeter with glue and 6 simple interrupted Ethilon 6-0 sutures. The detailed protocols of 20mg/mL tamoxifen(T5648, Sigma), 4μg/mL diphtheria toxin (D0564, Sigma), 20μg/mL periostin (2955-F2-050, R&D Systems), 400μg/mL LDN-193189 2HCl (7507, Selleck) and 0.5μg/mL BMP2 (355-BM-010, R&D Systems) injection were described in the main text or figure legends.

Harvesting dermal fibroblasts

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and the dorsal fur was clipped. Next, the 1cm×1cm dorsal skin was harvested using dissecting scissors by separation along fascial planes. The skin tissue was washed twice in PBS. Samples were cut into small pieces and digested on shaker at 1000rpm for 2h at 37 °C using 2.5mg/ml Collagenase IV (YEASEN, China). The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon), and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was washed once with PBS at 2000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was then resuspended in PBS + 1% FBS for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry analysis

All flow cytometry analysis on dermal fibroblasts described in this manuscript was performed on dissociated primary dermal fibroblasts after lineage-negative gating of hematopoietic, endothelial, and epithelial cell lineages, using CD45 (103133, Biolegend), CD31 (102423, Biolegend) and CD326 (EpCAM) (118225, Biolegend). The cell suspension was stained with BV421-conjugated CD31, CD45, and CD326 for 30 min on ice and washed three times with PBS and centrifuged. Cells were then resuspended in FACS buffer containing 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). FACS sorting (FACS Aria III) for DAPI-negative, CD31-negative, CD45-negative, and CD326-negative cells was then performed to isolate dermal fibroblasts.

Histology and Immunofluorescence staining

Masson staining and Immunofluorescence staining were performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded mice wound beds and human keloid, hypertrophic scar and normal scar biopsies. This study was approved by the Medical and Ethics Committees of Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University (KY-2024-091), and each patient signed an informed consent before enrolling in this study. For Masson staining, standard protocols were used with no modifications. For immunofluorescence staining, tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated followed by heat-induced antigen retrieval in citrate buffer at pH 9.0 for 20 min. Antibodies were applied, including anti-ADAM12 (sc293225, Santa Cruz), anti-Periostin (ab215199, Abcam), anti-Collagen I (ab270993, Abcam) , anti-Collagen III (ab7778, Abcam), anti-BMP2 (ab214821, Abcam), anti-PDGFRα (AF1062, R&D Systems) and anti-p-Smad1/5/8 (13820, Cell Signaling Technology) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Sections were washed with PBS three times, and then labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (ab150113, Abcam), 555 (ab150062, Abcam) or 647 (ab150135, Abcam) labeled secondary antibodies. Slides were coverslipped, using DAPI containing aqueous mounting medium. Images were obtained using a Nikon A1+ confocal laser-scanning microscope.

RNA in situ hybridization

RNA in situ hybridization was performed using RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescence Reagent Kit v.2 (323100, Advanced Cell Diagnostics). Briefly, prebaked paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated, then treated with hydrogen peroxide solution at room temperature for 10 min. Afterwards, the targets were retrieval in 95-105°C solution for 15 min using RNA-Protein Co-Detection Ancillary Kit (323180, Advanced Cell Diagnostics). Antibodies against different cell types, including anti-pan-Keratin (ab8068, abcam), anti-PDGFRα (AF1062, R&D Systems), anti-CD31 (AF3628, R&D Systems), anti-α-SMA (48938, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-F4/80 (14-4801, eBioscience), anti-CD3(14-0032, eBioscience) and anti-CD117 (14-1172, eBioscience), were incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, sections were incubated with 10% neutral buffered formalin for 30 min at room temperature and RNAscope® protease Plus for 30 min at 40°C. The Mm-Bmp2 probe (406661, Advanced Cell Diagnostics) was hybridized at 40°C for 2 h, followed by a signal amplification step. Fluorophore (ASOP 570, Asbio) was incubated at 40°C for 30 min. Images were acquired using a Nikon A1+ confocal laser scanning microscope.

Mechanical loading of wounds

The mechanical loading-induced hypertrophic scar model was established according to the model developed by Aarabi et al.[16, 17]. Briefly, a 20 mm-linear full-thickness incision was created along the dorsal midline of the mice, and then closed with sutures. On 3dpw, a loading device was secured over each wound with adhesive and simple interrupted sutures. Mechanical stretch was gradually loaded by activating the expansion screws by 4 mm per 2 days from 3dpw. LDN-193189 was injected along the suture line per 2 days after mechanical stretch was loaded, and the vehicle was injected into wounds for controls. The scar samples were collected after mice were sacrificed.

Isolation normal dermal fibroblasts (NFs) and culture NFs and NIH3T3 cells

The normal human skin tissues have excised from the epidermis and cut into small pieces using surgical scissors. Small tissues were placed in a dish with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco Life Technologies). After a few days, tissues were removed, and normal fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. Passage 3-6 NFs were performed. 100ng/ml recombinant BMP-2 Protein (355-BM-010, R&D Systems) were added to NFs and NIH3T3 cells, which were stimulated for 24-48 hours before harvesting.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed as previously described[18]. Briefly, total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan). Gene-specific primer pairs were designed with Primer Premier 5.0 software. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol, with the following gene-specific primers:

DTR: Fwd 5'-GGAGCACGGGAAAAGAAAG-3' and Rev 5'-GAGCCCGGAGCTCCTTCACA-3';

Mouse Gapdh: Fwd 5'-GGTCCCAGCTTAGGTTCATC-3' and Rev 5'- ACAATCTCCACTTTGCCACT-3';

Mouse Id1: Fwd 5'-AGGTGGTACTTGGTCTGTCGG-3' and Rev 5'-GCTCACTTTGCGGTTCTGG-3';

Mouse Id2: Fwd 5'-CATCCTGTCCTTGCAGGCAT-3' and Rev 5'-GAGAACGACACCTGGGCAAG-3';

Mouse Id3: Fwd 5'-GCATCTCCCGATCCAGACAG-3' and Rev 5'-AGGCAGGATTTCCCATGCAA-3';

Mouse Adam12: Fwd 5'-AGACGTGCTGACTGTGCAAC-3' and Rev 5'-CCGTGTGATTTCGAGTGAGAGA-3';

Mouse Postn: Fwd 5'-TGGTATCAAGGTGCTATCTGCG-3' and Rev 5'-AATGCCCAGCGTGCCATAA-3';

Mouse Comp: Fwd 5'-ACTGCCTGCGTTCTAGTGC-3' and Rev 5'-CGCCGCATTAGTCTCCTGAA-3';

Mouse Aspn: Fwd 5'-AAGGAGTATGTGATGCTACTGCT-3' and Rev 5'-ACATTGGCACCCAAATGGACA-3';

Mouse Col11a1: Fwd 5'-ACAAAACCCCTCGATAGAAGTGA-3' and Rev 5'-CTCAGGTGCATACTCATCAATGT-3';

Mouse Col1a1: Fwd 5'-TGGAAACCCGAGGTATGCTT-3' and Rev 5'-GGTCCCTCGACTCCTACATCT-3';

Mouse Col3a1: Fwd 5'-AACCTGGCCGAGATGGAACC-3' and Rev 5'-GCGACCACTTTCTCCTTGACT-3';

Human GAPDH: Fwd 5'-TTGGCCAGGGGTGCTAAG-3' and Rev 5'-AGCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3';

Human ID1: Fwd 5'-CTGCTCTACGACATGAACGG-3' and Rev 5'-GAAGGTCCCTGATGTAGTCGAT-3';

Human ID2: Fwd 5'-GCTATACAACATGAACGACTGCT-3' and Rev 5'-AATAGTGGGATGCGAGTCCAG-3';

Human ID3: Fwd 5'-CTTCCCATCCAGACAGCCGA-3' and Rev 5'-CCTTAGAACTTGGGGGTGGG-3';

Human ADAM12: Fwd 5'-GACTACAACGGGAAAGCAA-3' and Rev 5'-GAGCGAGGGAGACATCAGTA-3';

Human POSTN: Fwd 5'-GAGACAAAGTGGCTTCCG-3' and Rev 5'-CTGTCACCGTCACATCCT-3';

Human COMP: Fwd 5'-AGCGAGTGCCACGAGCAT-3' and Rev 5'-CGGGAAGCCGTCTAGGTCA-3';

Human ASPN: Fwd 5'-CAGTCCCAACCAACATTC-3' and Rev 5'-GGACAGATACAGCCTTCG-3';

Human COL11A1: Fwd 5'-AAGGCTCAGATACTGCTTACA-3' and Rev 5'-CTCCCAACCTCAACACCA-3';

Human COL1A1: Fwd 5'-TGTGCGATGACGTGATCTGTGA-3' and Rev 5'-CTTGGTCGGTGGGTGACTCTG-3';

Human COL3A1: Fwd 5'-CAAATAGAAAGCCTCATTAGTCC-3' and Rev 5'-GCATCCTTGGTTAGGGTCA-3'.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as previously described. Briefly, cells were lysed in 1×SDS-PAGE loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8, 2% (W/V) SDS, 0.1% (W/V) BPB, 10% (V/V) glycerol) containing 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, and the lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes for western blot using chemiluminescence detection reagents (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA). Antibodies were applied, including anti-Collagen I for NIH3T3 cell (ab270993, abcam), anti-Collagen I for normal fibroblast (91144, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Collagen III (ab184993, abcam), anti-Asporin (ab154404, abcam), anti-Periostin (ab14041, abcam) and anti-COMP (ab74524, abcam), anti-ADAM12 (14139-1-AP, Proteintech), anti-p-SMAD1/5/8 (13820, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-SMAD1 (6944, Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-GAPDH (60004-1-Ig, Proteintech).

Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 19.0). Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Data represent mean ± standard deviation. A two-tailed, unpaired or paired Student t-test or the One-way ANOVA test was employed to compare the values between subgroups for quantitative data. Pearson correlation was used to measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Adam12+ fibroblasts undergo dynamic expansion during skin wound healing and are essential for wound-associated skin scarring and fibrosis

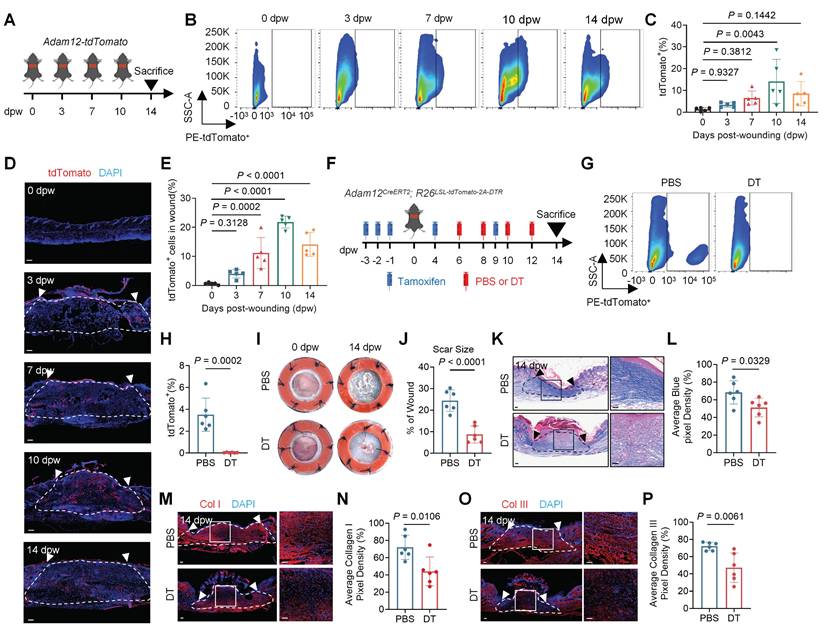

Our previously published studies suggested that ADAM12+ mesenchymal fibroblast subpopulation increased in keloid, an abnormal human skin scar, compared with normal scar[14]. Keloid often results from skin injury. To delineate the temporal dynamics of ADAM12+ fibroblast after skin injury, we analyzed the single cell RNA-seq (scRNAseq) data of mouse skin wound healing[19]. The results showed that a new fibroblast subpopulation highly expressed Adam12 generated at Day 4 and Day 7 post-wounding (Supplementary information, Figure S1A, B). These results suggested that Adam12+ fibroblast may increase after skin wounding. To verify this, we generated transgenic mice, termed Adam12-tdTomato, expressing tdTomato under control of the Adam12 promoter (Figure 1A). In the mice, cells express Adam12 would express tdTomato. We then performed flow cytometry analysis on unwound and wounded back skin at day 3 post-wounding (3dpw), 7dpw, 10dpw and 14dpw, covering the inflammatory phase, proliferative phase and remodeling phase of skin wound healing. A lineage gate (Lin) for hematopoietic (CD45), endothelial (CD31), and epithelial (CD326) cell markers was used as a negative gate to isolate fibroblasts (Lin-) (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). The results showed that the percentage of tdTomato+ fibroblasts increased significantly after wounding, and then decreased at 14dpw, the time point at which the wound is fully healed and forms scars (Figure 1B, C). The immunofluorescence staining results for tdTomato also supported the findings obtained from the flow cytometry analysis (Figure 1D, E). Taken together, these results suggest that Adam12+ fibroblasts exhibit a dynamic of first increasing and then decreasing after skin wounding.

To define the role of Adam12+ cells in skin scarring and fibrosis, we intradermally injected a low dose of diphtheria toxin (DT) into mice expressing an inducible DT receptor (iDTR) in Adam12+ cells (Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR) (Figure 1F). Flow cytometry and qRT-PCR analysis indicated that Adam12+ cells were efficiently ablated after DT administration (Figure 1G, H and Supplementary information, Figure S1D). DT treated wounds showed significantly reduced final scar size (24.41±5.005% vs 8.713±3.957%, P < 0.001) after wound healing in comparison with control wounds (Figure 1I, J). Masson staining revealed reduced collagen density, evidenced by a higher ratio of red to blue staining, in DT-treated as compared with control wounds at 14dpw (Figure 1K, L). The immunofluorescence staining results also showed that expression of collagen I and III decreased in DT-treated as compared with control group (Figure 1M-P). In conclusion, these results indicate that depletion of Adam12+ fibroblasts during wound healing process will decrease the degree of skin scarring and fibrosis.

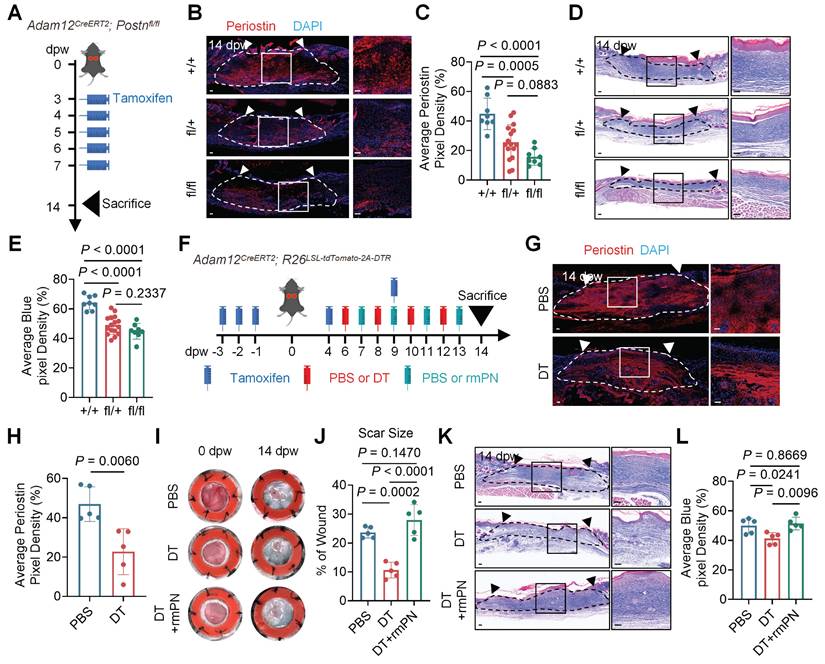

Periostin mediates the pro-fibrogenic activity of Adam12+ fibroblasts during skin scarring

Our previously published study suggested that periostin (encoded by POSTN) is highly expressed in ADAM12+ mesenchymal fibroblast subpopulation[14]. To see whether periostin expressed in mouse Adam12+ fibroblasts, we analyzed the single cell RNA-seq data of mouse skin wound healing. The results showed that most of Postn expressed in Adam12+ fibroblasts (Supplementary information, Figure S2A). We next performed immunofluorescence staining analysis and found that periostin was increased after skin injury in mouse (Supplementary information, Figure S2B, C). To explore the role of periostin in Adam12+ fibroblasts of mouse wound, we generated Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/+ and Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/fl mice for Adam12+ cells-specific Postn deletion. We tamoxifen-induced and wounded Adam12CreERT2;Postn+/+ (Postn+/+; control), Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/+, and Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/fl mice and harvested wounds at 14dpw (Figure 2A). The expression of periostin decreased significantly in Postnfl/+ and Postnfl/fl mice wounds compared with Postn+/+ control mice wounds, suggesting successful Postn deletion (Figure 2B, C). Masson staining and immunofluorescence staining results showed that the expression of collagens decreased in Postnfl/fl mice wounds compared with Postn+/+ and Postnfl/+ mice wounds (Figure 2D, E and Supplementary information, Figure S2D-G). These results indicate that periostin is necessary for Adam12+ fibroblasts' functions in skin scarring.

Adam12+ fibroblasts undergo dynamic expansion during skin wound healing and are essential for wound-associated skin scarring and fibrosis. A Schematic depicting wounding of Adam12-tdTomato mice for a temporally defined assessment of Adam12+ fibroblasts. B, C Flow cytometry analysis of tdTomato in Adam12-tdTomato mice on unwound and wounded back skin at day 0 post-wounding (0dpw), 3dpw, 7dpw, 10dpw and 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). D, E Immunofluorescence staining analysis for tdTomato in C57BL/6J mice on unwound and wounded back skin at 0dpw, 3dpw, 7dpw, 10dpw and 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). F Schematic depicting wounding of Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice and depletion of Adam12+ cells in vivo. G, H Flow cytometry analysis of tdTomato indicated that Adam12+ cells were efficiently ablated after DT administration. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). I, J Representative photographic images of wounds at 0 dpw and 14 dpw in both PBS and DT-treated wounds of Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). K, L Masson staining on wound tissues of DT treated mice and control mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. M-P, Immunofluorescence staining analysis for Collagen I and Collagen III on wound tissues of DT treated mice and control mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. One-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance in C and E. Two-tailed Student's unpaired t-test was used to determine statistical significance in H, J, L, N and P.

Periostin mediates the pro-fibrogenic activity of Adam12+ fibroblasts during skin scarring. A Schematic depicting wounding and tamoxifen induction of Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/fl mice for Adam12+ cells-specific Postn deletion. B, C Immunofluorescence staining analysis for periostin on wound tissues of Adam12CreERT2;Postn+/+, Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/+, and Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/fl mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=8-16 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. D, E Masson staining on wound tissues of Adam12CreERT2;Postn+/+, Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/+, and Adam12CreERT2;Postnfl/fl mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=8-16 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. F Schematic depicting wounding, 2mg tamoxifen induction, 200ng DT injection and 1μg rmPOSTN (rmPN) injection of Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice. G, H Immunofluorescence staining analysis for periostin on wound tissues of PBS group and DT group Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. I, J Representative photographic images of wound tissues of PBS group, DT group and DT+rmPOSTN group Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice at 0dpw and 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). K, L Masson staining on wound tissues of PBS group, DT group and DT+rmPOSTN group Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. One-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance in C, E, J and L. Two-tailed Student's unpaired t-test was used to determine statistical significance in H.

To determine if periostin is sufficient for the functions of Adam12+ fibroblasts in skin scarring, we injected periostin into the wound of Adam12+ fibroblasts depletion mice (Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR) (Figure 2F). Immunofluorescence staining and qRT-PCR analysis suggested that the expression of periostin (46.95±8.778% vs 22.74±11.66%, P=0.006) and DTR decreased significantly in the DT-treated group compared with the control group (Figure 2G, H and Supplementary information, Figure S2H). Photographic images suggested that periostin injection into the wounds of Adam12+ fibroblasts depletion mice rescued the scar size (PBS: 23.68±1.941%, DT: 10.64±2.732%, DT+rmPN: 27.97±5.294%) (Figure 2I, J). Masson staining and immunofluorescence staining analysis suggested that periostin injection into the wounds of Adam12+ fibroblasts depletion mice rescued the expression of collagens in the scars (Figure 2K, L and Supplementary information, Figure S2I-L). Collectively, these experiments establish periostin as both necessary and sufficient to mediate Adam12+ fibroblast-dependent skin scarring and fibrosis.

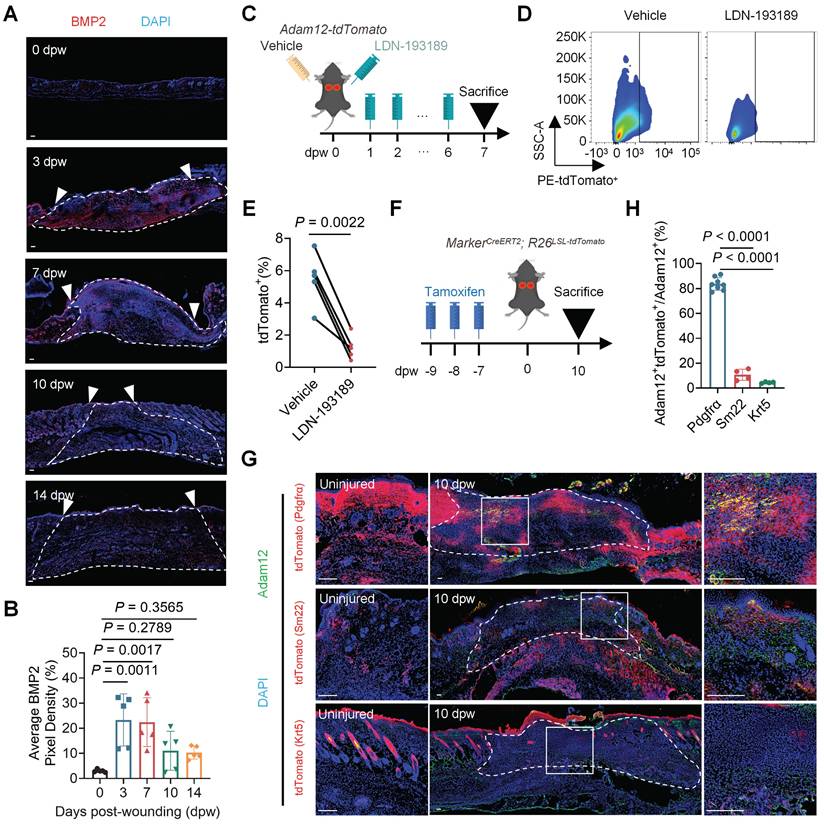

Adam12+ fibroblasts predominantly derive from resident fibroblasts in unwounded skin

We next want to delineate the cellular origins of Adam12+ fibroblasts after skin injury. One important characteristic of Adam12+ fibroblasts is highly expressed osteogenesis and chondrogenesis differentiation associated genes, such as Adam12, Postn, Aspn and Runx2[14]. BMP2 signaling is known to play an important role in osteogenesis and chondrogenesis processes[20], and our previously published keloid associated paper suggested that BMP2 could regulate the expression of POSTN in human fibroblasts[21]. These analyses lead us to speculate that BMP2 signaling may regulate the generation of Adam12+ fibroblasts. To test this, we first detected the expression of BMP2 on unwound and wounded back skin at different days. The results showed that the expression of BMP2 also exhibited a dynamic of first increasing and then decreasing after skin wounding (Figure 3A, B). We next tried to explore the source cells of BMP2 at 3 dpw by using RNAscope because BMP2 was secretory protein. The results showed that multiple cells, including fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells and pericytes, expressed Bmp2 mRNA at 3dpw (Supplementary information, Figure S3A, B), suggesting that Bmp2 is multi-source after skin injury. We next inhibited BMP2 signaling in Adam12-tdTomato mice skin wound by injecting LDN-193189, a specific BMP2 signaling pathway small molecule inhibitors (Figure 3C). The level of p-Smad1/5/8, the downstream effectors of BMP2 signaling, decreased significantly in LDN-193189 group compared with the control group (Supplementary information, Figure S3C-E). Flow cytometry analysis results showed that administration of LDN-193189 nearly completely inhibited the generation of Adam12+ fibroblasts (Figure 3D, E). The immunofluorescence staining results for Adam12 in C57BL/6J mice also supported the findings (Supplementary information, Figure S3F, G). Collectively, these data establish BMP2 as the essential upstream regulator of Adam12+ fibroblast lineage commitment during skin scarring.

To delineate the cellular origins of Adam12+ fibroblasts after skin injury, we next analyzed the expression of BMP2 receptors, Bmpr1(Bmpr1a and Bmpr1b) and Bmpr2, in the single cell RNA-seq data of mouse skin wound healing. The results showed that fibroblasts, keratinocytes and pericytes (smooth muscle cells) expressed Bmpr1a, nearly no cells expressed Bmpr1b, and fibroblasts, keratinocytes, pericytes (smooth muscle cells) and endothelial cells expressed Bmpr2 (Supplementary information, Figure S3H). Based on the canonical requirement for Bmpr1/Bmpr2 heterodimerization in Bmp2 signal transduction, we predicted Adam12+ fibroblasts derive from fibroblasts, keratinocytes or pericytes (smooth muscle cells). To identify which cells Adam12+ fibroblasts originate from, we performed genetic lineage tracing of fibroblasts, keratinocytes and pericytes (smooth muscle cells) during skin wound healing (Figure 3F). We used PdgfraCreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice to label fibroblasts, Krt5CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice to label keratinocytes and Sm22CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice to label pericytes (smooth muscle cells), respectively. Tamoxifen was injected 3 times, and injected mice were maintained for 7 days before wounding to exclude the interference of tamoxifen in lineage tracing analysis (Figure 3F). The mice were sacrificed at 10dpw and immunofluorescence staining was performed with Adam12 antibody. The results showed that about 83% of Adam12+ cells were tdTomato+ in PdgfraCreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice, about 11% of Adam12+ cells were tdTomato+ in Sm22CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice and about 4% of Adam12+ cells were tdTomato+ in Krt5CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice (Figure 3G, H). These data conclusively demonstrate resident fibroblasts are the predominant source of Adam12+ profibrotic cells during cutaneous wound repair.

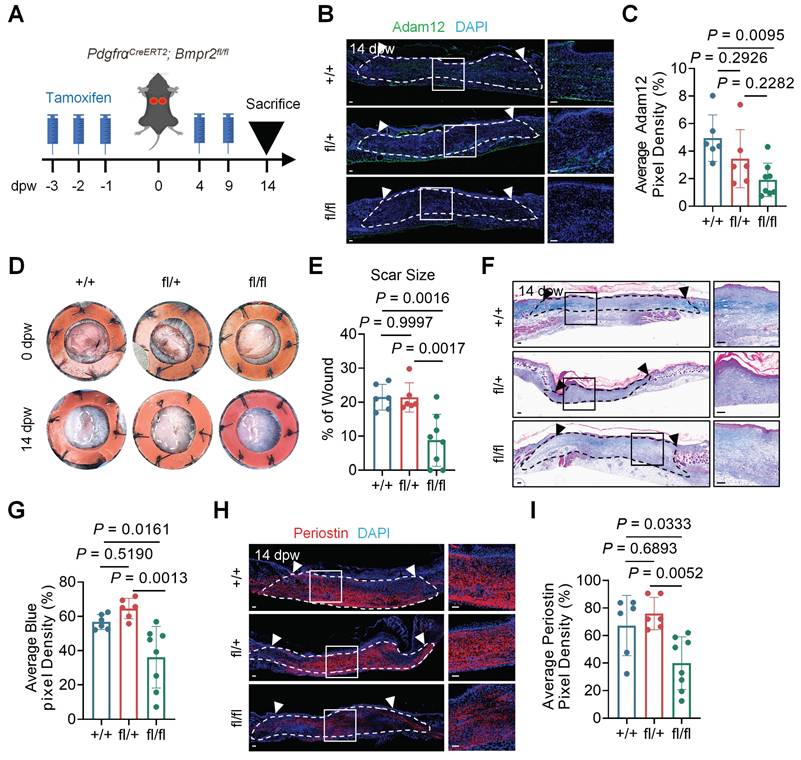

BMP2 signaling is required for the lineage commitment of resident dermal fibroblasts into pro-fibrogenic Adam12+ fibroblasts

To definitively establish BMP2's role in the generation of Adam12+ fibroblasts, we conditional knocked out BMP2 receptor Bmpr2 in fibroblasts by using PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice (Figure 4A). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that Bmpr2 knock-out in fibroblasts decreased the expression of p-Smad1/5/8 in fibroblasts (Supplementary information, Figure S4A, B). Bmpr2 knock-out in fibroblasts decreased the number of Adam12+ cells after wounding (Figure 4B, C). Final scar size decreased significantly in PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice (8.796±7.629%) as compared with PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+ mice (21.39±4.289%) and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+ mice (21.46±3.803%) (Figure 4D, E). Masson staining and immunofluorescence staining results revealed decreased collagen density and expression of collagens and periostin in PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice as compared with PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+ mice and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+ mice (Figure 4F-I and Supplementary information, Figure S4C-F). These genetic loss-of-function studies conclusively demonstrate BMP2 signaling is required for the formation of Adam12+ fibroblasts and scarring after skin injury.

Adam12+ fibroblasts predominantly derive from resident fibroblasts in unwounded skin. A, B Immunofluorescence staining analysis for BMP2 in C57BL/6J mice on unwound and wounded back skin at 0dpw, 3dpw, 7dpw, 10dpw and 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. C Schematic depicting wounding, vehicle injection and 20μg BMP2 inhibitor LDN-193189 2HCl injection of Adam12-tdTomato mice. D, E Flow cytometry analysis of tdTomato on vehicle injection or LDN-193189 2HCl injection wounds of Adam12-tdTomato mice. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). F Schematic depicting tamoxifen induction and wounding of MarkerCreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice for lineage tracing. G, H Immunofluorescence staining analysis for tdTomato and Adam12 on wounds of PdgfraCreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato, Sm22CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato and Krt5CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice at 10dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=8 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice. n=4 wounds for Sm22CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato and Krt5CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato mice). Scale bar = 100μm. Two-tailed Student's paired t-test was used to determine statistical significance in E. One-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance in B and H.

Augmentation of BMP2 signaling drives expansion of Adam12+ fibroblasts and exacerbates skin scarring and fibrosis

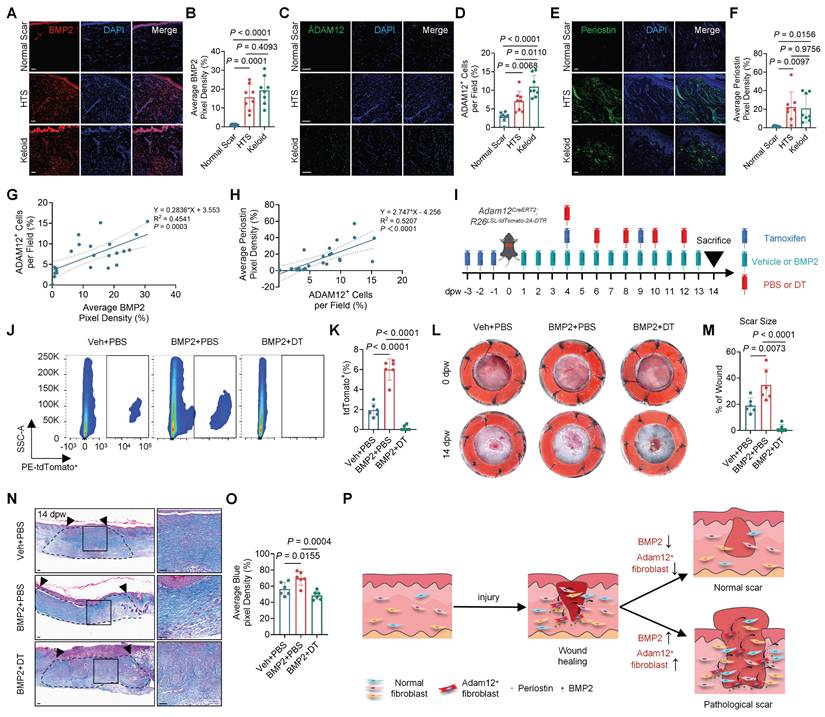

Pathological scarring disorders, including hypertrophic scars and keloids, predominantly arise from aberrant wound healing responses following skin injury. To assess the clinical relevance of our findings, we analyzed the expression of ADAM12⁺ fibroblast markers and BMP2 in human scar specimens. ADAM12, POSTN, and BMP2 levels were significantly elevated in hypertrophic scars and keloids compared with normal scars (Figure 5A-F). Positive correlations were observed between BMP2 and ADAM12, and between ADAM12 and POSTN (Figure 5G, H), suggesting that BMP2 overexpression may promote pathological scarring via expansion of the ADAM12⁺ fibroblast population.

To examine the effect of BMP2 on Adam12⁺ fibroblast activation in vivo, we injected 25 ng BMP2 into dorsal wounds of Adam12-tdTomato mice (Supplementary information, Figure S5A). Flow cytometry revealed a significant increase in Adam12⁺ cells in BMP2-treated wounds compared with controls (Supplementary information, Figure S5B, C). In parallel, we stimulated primary normal fibroblasts (NFs) and NIH3T3 cells with recombinant BMP2 in vitro. BMP2 treatment markedly upregulated the expression of its canonical downstream targets ID1, ID2, and ID3, and increased phosphorylation of SMAD1/5/8 (Supplementary information, Figure S5D-G). Expression of an ADAM12⁺ fibroblast marker as well as collagen I and collagen III were also significantly elevated (Supplementary information, Figure S5H-K).

BMP2 signaling is required for the lineage commitment of resident dermal fibroblasts into pro-fibrogenic Adam12+ fibroblasts. A Schematic depicting wounding and tamoxifen induction of PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice for fibroblasts-specific Bmpr2 deletion. B, C Immunofluorescence staining analysis for Adam12 on wound tissues of PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+, and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+ and n=8 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl). Scale bar = 100μm. D, E Representative photographic images of wound tissues of PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+, and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice at 0dpw and 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+ and n=8 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl). F, G Masson staining on wound tissues of PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+, and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+ and n=8 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl). Scale bar = 100μm. H, I Immunofluorescence staining analysis for periostin on wound tissues of PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+, and PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl mice at 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2+/+, PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/+ and n=8 wounds for PdgfraCreERT2;Bmpr2fl/fl). Scale bar = 100μm. One-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance in C, E, G and I.

Augmentation of BMP2 signaling drives expansion of Adam12+ fibroblasts and exacerbates skin scarring. A-F, Immunofluorescence staining analysis for BMP2, ADAM12 and Periostin in normal scar, hypertrophic scar (HTS) and keloid. Error bars represent SD (n=8). Scale bar = 100μm. G The correlation analyses between the expression of BMP and ADAM12. The range between the two dashed lines represents the 95% confidence interval. H The correlation analyses between the expression of ADAM12 and periostin. The range between the two dashed lines represents the 95% confidence interval. I Schematic depicting wounding, 2mg tamoxifen induction, 200ng DT injection and 25ng BMP2 injection of Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice. J, K Flow cytometry analysis of tdTomato on vehicle+PBS injection, BMP2+PBS injection and BMP2+DT injection wounds of Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). L, M Representative photographic images of wound tissues of vehicle+PBS group, BMP2+PBS group and BMP2+DT group Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice at 0dpw and 14dpw. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). N, O Masson staining on vehicle+PBS injection, BMP2+PBS injection and BMP2+DT injection wounds of Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR mice. Error bars represent SD (n=6 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. N Schematic illustration showing that abnormal high-expressed BMP2 in healed wound may lead to pathologic scars. One-way ANOVA test was used to determine statistical significance in B, D, F, K, M and O. Pearson correlation was used to measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two variables in G and H.

To test whether BMP2-induced skin scarring depends on Adam12⁺ cells, we used Adam12-lineage ablation mice (Adam12CreERT2; R26LSL-tdTomato-2A-DTR) and injected BMP2 into dorsal wounds (Figure 5I). Flow cytometry analysis indicated that the number of Adam12+ cells were significantly increased in BMP2+PBS wounds and were efficiently ablated in BMP2+DT wounds compared with control wounds (Figure 5J, K). BMP2+PBS treated wounds showed significantly increased final scar size while BMP2+DT treated wounds decreased (Veh+PBS: 19.09±5.69%, BMP2+PBS: 34.68±12.15%, BMP2+DT: 1.64±2.91%) compared with control wounds at 14dpw (Figure 5L, M). Masson's trichrome and immunofluorescence staining revealed higher collagen density in BMP+PBS wounds but lower density in BMP2 + DT wounds (Figure 5N, O and Supplementary information, Figure S6A-D). Immunofluorescence staining showed that periostin expression was also markedly elevated in BMP2+PBS wounds and decreased in BMP2 + DT wounds. (Supplementary information, Figure S6E, F). Together, these results demonstrate that BMP2-driven skin fibrosis requires Adam12⁺ fibroblasts and is mediated through periostin.

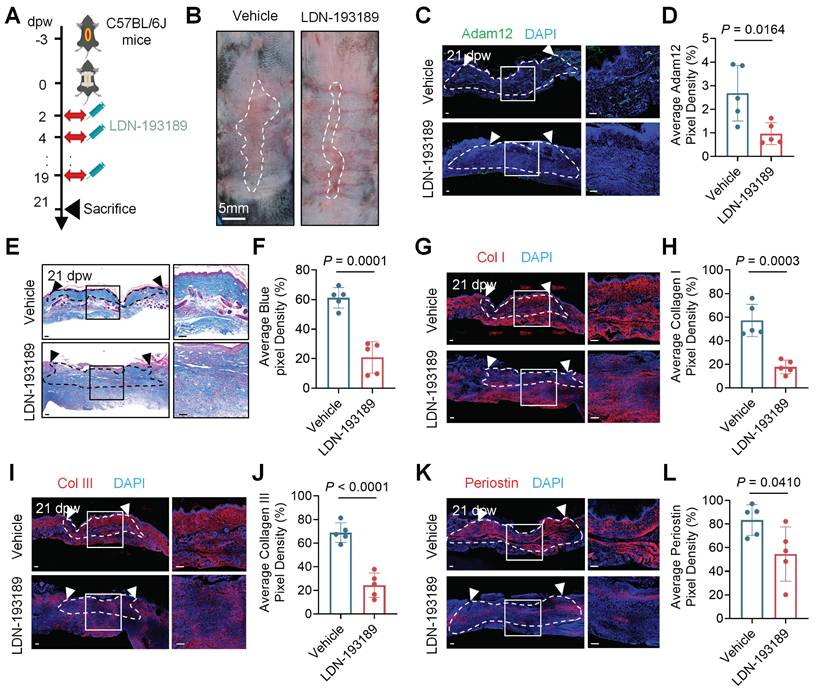

BMP2 represents a promising therapeutic target for pathological scars

Because the BMP2 expression upregulated in pathological scarring and we found that BMP2 increased in the tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model (Supplementary information, Figure S7A, B), we next want to test the therapeutic effect of BMP2 inhibitor on pathological scars. We injected LDN-193189 into the tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model (Figure 6A). The level of p-Smad1/5/8 decreased significantly in LDN-193189 group compared with the control group (7.712±1.844% vs 2.570±1.652%, P=0.0017) (Supplementary information, Figure S7C, D). The results showed that LDN-193189 treatment significantly inhibited the development of hypertrophic scar in mice (Figure 6B). Masson staining and immunofluorescence staining analysis revealed reduced collagen density and expression of Adam12, collagens and periostin in LDN-193189-treated group compared with the control group (Figure 6C-L). These preclinical results position BMP2 inhibition as a viable therapeutic strategy for skin fibrotic diseases.

BMP2 represents a promising therapeutic target for pathological scars. A Schematic depicting wounding, vehicle injection and 20μg BMP2 inhibitor LDN-193189 2HCl injection of tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model. B Representative photographic images of scar tissues of vehicle injection or LDN-193189 2HCl injection group in tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 5mm. C, D Immunofluorescence staining analysis for Adam12 on vehicle injection or LDN-193189 2HCl injection wounds of tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. E, F Masson staining on vehicle injection and LDN-193189 2HCl injection wounds of tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. G-L, Immunofluorescence staining analysis for Collagen I, Collagen III and periostin on vehicle injection and LDN-193189 2HCl injection wounds of tension induced hypertrophic scar mice model. Error bars represent SD (n=5 wounds). Scale bar = 100μm. Two-tailed Student's unpaired t-test was used to determine statistical significance in D, F, H, J and L.

Discussion

Despite decades of investigation, the molecular pathogenesis underlying skin scarring remains incompletely characterized. In addition, treatments to prevent or treat pathological scarring are scarce and not effective. Herein, we identified Adam12+ fibroblasts as important functional cells in skin scarring, and explored the origin and pathogenesis of Adam12+ fibroblasts in the skin fibrotic process. Considering that Adam12+ fibroblasts were found to be increased and important in the development of multiple fibrotic diseases, including acute tissue injury induced fibrosis[22], human fibrotic liver and bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis[23], our findings are vital for understanding the pathogenesis of fibrosis and may provide new targets for the therapy of fibrotic diseases.

BMP2 plays a critical role in several developmental processes, including cardiogenesis, somite formation, and neurogenesis[20, 24]. Additionally, BMP2 is involved in osteogenesis, adipogenesis, chondrogenesis, cardiac differentiation, and the maintenance of the nervous system[20, 24]. However, its role in skin wound healing and scarring remains unclear. While BMP signaling has been shown to promote regenerative healing in large wounds by inducing the adipogenic conversion of myofibroblasts[25], our findings indicate that BMP2 signaling increases following wounding and is essential for the generation of Adam12+ fibroblasts and skin scarring (Figure 3 and 4). This dual function of BMP2 emphasizes the significance of the tissue microenvironment—such as wound size, mechanical stress, inflammatory signals, and interacting pathways—in determining the outcome of BMP signaling. In scarring conditions, early BMP2 expression likely interacts with strong profibrotic signals, directing fibroblasts towards matrix-producing phenotypes rather than adipogenic pathways.

As far as we know, this is the first time that the link between BMP2 signaling pathway and Adam12+ fibroblast generation has been established. We further demonstrated that BMP2 expression is significantly elevated in hypertrophic scars and keloids compared with normal scars, and BMP2 inhibitor treatment inhibited the fibrotic process of pathological scar (Figure 5 and 6). These results implied that abnormally high levels of BMP2 may lead to skin fibrotic diseases such as hypertrophic scars and keloids. However, as a pleiotropic morphogen vital for development and homeostasis, BMP2 acts upstream in broad physiological networks, making direct therapeutic targeting challenging due to potential systemic side effects[26]. Therefore, while BMP2 is a key mechanistic driver, future efforts should focus on identifying and modulating more downstream, disease-specific effectors within this pathway.

Our results showed that BMP2 signaling and Adam12+ fibroblasts exhibited a trend of first increasing and then decreasing during wound healing processes (Figure 1B-E and Figure 3A, B). However, BMP2 signaling and Adam12+ fibroblasts increased significantly in hypertrophic scar and keloid compared with normal scars (Figure 5A-F). The mechanism of downregulation of BMP2 during skin healing process and persistent elevation of BMP2 in pathological scars remains elusive. Our recently published paper suggested that a susceptibility locus of keloid could regulate the expression of BMP2 in keloid[21], implying that genetic factors may be the reason for the elevation of BMP2 expression in some pathological scar patients. Our future work will focus on illustrating the mechanism that downregulation of BMP2 and Adam12+ fibroblasts in normal scar and increasing of BMP2 in pathological scars.

Profibrotic fibroblasts in fibrotic diseases have been reported to be multi-source, including resident fibroblasts, fibrocytes, epithelial cells, pericytes and endothelial cells[1, 27]. Previous research suggested that Adam12+ fibroblasts may originate from neural crest cells-derived Schwann cells and perivascular cells, and Adam12+ fibroblasts originating from perivascular cells may be profibrotic progenitors in cardiotoxin-injured tibialis anterior muscles of mice[22]. Our genetic lineage tracing analysis indicated that about 83% of Adam12+ cells were from resident fibroblasts of unwound skin and about 11% of Adam12+ cells were from pericytes (or smooth muscle cells) (Figure 3G, H). Our results are consistent with previous findings that part of Adam12+ fibroblasts originates from perivascular cells, but our findings suggested that Adam12+ cells mainly originate from resident fibroblasts in skin wound healing[22]. Recent research suggested that fascia was a major fibroblasts source for deep skin wound[28, 29]. Resident fibroblasts in fascia may migrate into the wound bed and change their identity into Adam12+ fibroblast to contribute to skin scarring and fibrosis.

Our study identifies a distinct subset of Adam12-expressing fibroblasts within the injured microenvironment. Adam12 is a multifunctional protein from the Adam family. Its structure includes a metalloproteinase domain, a disintegrin domain, a cysteine-rich region, and a cytoplasmic tail[30, 31]. These domains enable Adam12 to function as an active protease, cleaving substrates such as Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-3 (IGFBP-3), which increases the local bioavailability of IGF-1, a key mitogen and survival factor for mesenchymal cells[32]. Additionally, Adam12's disintegrin and cysteine-rich regions mediate interactions with cell surface receptors like integrins and syndecans, influencing cell adhesion, spreading, and intracellular signaling[32]. In pathological conditions such as cancer and fibrosis, Adam12 is frequently upregulated and linked to processes like cell proliferation, invasion, and tissue remodeling[30]. Within the Adam12+ fibroblast subset observed in our study, these proteolytic and adhesive functions may converge to promote a pro-fibrotic phenotype. Specifically, Adam12 may enhance fibroblast proliferation and survival through IGF-1 signaling, while also reinforcing cell-matrix interactions, thereby sustaining collagen deposition and scar maturation. Although our data suggest that this population is induced by BMP2 signaling and linked to periostin production, the precise roles of Adam12's enzymatic and adhesive functions in scar fibrosis require further exploration.

Periostin has been shown to be important for fibroblast proliferation, fibroblast migration, collagen expression and myofibroblast generation in skin wound healing[33-35]. However, the source cells of periostin in skin wound healing were not very clear. Here, our scRNAseq analysis, conditional knock-out and cell ablation experiments indicated that periostin was necessary and sufficient for skin scarring and Adam12+ fibroblasts were the main source cells of periostin (Figure 2). These findings both confirm periostin established pro-fibrogenic role and newly identify Adam12+ fibroblasts as its predominant cellular source, significantly advancing our understanding of periostin biology in skin scarring.

In conclusion, we have delineated a BMP2-Adam12+ fibroblast-periostin signaling axis and indicate that BMP2 induces Adam12+ fibroblasts generation to dictate the degree of wound-associated skin scarring and fibrosis by secreting periostin. These findings will expand our understanding of the mechanism of skin scarring and fibrosis in depth, and may provide potential targets for effective therapies of fibrotic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgements

The present work is the result of all joint efforts. We wish to express our sincere appreciation to all those who have offered invaluable help during this study.

Funding statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373457, 82473506), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515010120) and the Science and Technology Foundation of Guangzhou (2025A04J5302).

Author contribution statement

Conceptualization: C.D., B.Y., Z.R.; Methodology: C.D., B.Y., Z.R., J.C., J.S., K.L., X.X., L.Z., Z.C., Q.C., L.Y., Y.S.; Formal Analysis: C.D., J.C., K.L., J.S., X.X., D.Z.; Investigation: C.D., B.Y., Z.R., J.C., J.S., K.L., X.X., D.Z., Z.C.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation: C.D., B.Y., Z.R., J.C; Writing-Review and Editing: C.D., B.Y., Z.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of South China Agricultural University (2023D105). Human protocols were approved by the Medical and Ethics Committees of Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University (KY-2024-091), and each patient signed an informed consent before enrolling in this study.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Talbott HE, Mascharak S, Griffin M, Wan DC, Longaker MT. Wound healing, fibroblast heterogeneity, and fibrosis. Cell stem cell. 2022;29:1161-80

2. Younesi FS, Miller AE, Barker TH, Rossi FMV, Hinz B. Fibroblast and myofibroblast activation in normal tissue repair and fibrosis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2024;25:617-38

3. Peña OA, Martin P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2024;25:599-616

4. Cohen AJ, Nikbakht N, Uitto J. Keloid Disorder: Genetic Basis, Gene Expression Profiles, and Immunological Modulation of the Fibrotic Processes in the Skin. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2023 15

5. Jeschke MG, Wood FM, Middelkoop E, Bayat A, Teot L, Ogawa R. et al. Scars. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2023;9:64

6. Gu Y, Wu S, Fan J, Meng Z, Gao G, Liu T. et al. CYLD regulates cell ferroptosis through Hippo/YAP signaling in prostate cancer progression. Cell death & disease. 2024;15:79

7. Andrews JP, Marttala J, Macarak E, Rosenbloom J, Uitto J. Keloids: The paradigm of skin fibrosis - Pathomechanisms and treatment. Matrix biology: journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2016;51:37-46

8. Macarak EJ, Wermuth PJ, Rosenbloom J, Uitto J. Keloid disorder: Fibroblast differentiation and gene expression profile in fibrotic skin diseases. Experimental dermatology. 2021;30:132-45

9. Ganier C, Rognoni E, Goss G, Lynch M, Watt FM. Fibroblast Heterogeneity in Healthy and Wounded Skin. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2022 14

10. Mascharak S, desJardins-Park HE, Longaker MT. Fibroblast Heterogeneity in Wound Healing: Hurdles to Clinical Translation. Trends in molecular medicine. 2020;26:1101-6

11. Rinkevich Y, Walmsley GG, Hu MS, Maan ZN, Newman AM, Drukker M. et al. Skin fibrosis. Identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Science (New York, NY). 2015;348:aaa2151

12. Leavitt T, Hu MS, Borrelli MR, Januszyk M, Garcia JT, Ransom RC. et al. Prrx1 Fibroblasts Represent a Pro-fibrotic Lineage in the Mouse Ventral Dermis. Cell reports. 2020;33:108356

13. Driskell RR, Lichtenberger BM, Hoste E, Kretzschmar K, Simons BD, Charalambous M. et al. Distinct fibroblast lineages determine dermal architecture in skin development and repair. Nature. 2013;504:277-81

14. Deng CC, Hu YF, Zhu DH, Cheng Q, Gu JJ, Feng QL. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and increased mesenchymal fibroblasts in human fibrotic skin diseases. Nature communications. 2021;12:3709

15. Januszyk M, Griffin M, Mascharak S, Talbott HE, Chen K, Henn D. et al. Multiplexed evaluation of mouse wound tissue using oligonucleotide barcoding with single-cell RNA sequencing. STAR protocols. 2023;4:101946

16. Aarabi S, Bhatt KA, Shi Y, Paterno J, Chang EI, Loh SA. et al. Mechanical load initiates hypertrophic scar formation through decreased cellular apoptosis. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2007;21:3250-61

17. Mascharak S, desJardins-Park HE, Davitt MF, Griffin M, Borrelli MR, Moore AL. et al. Preventing Engrailed-1 activation in fibroblasts yields wound regeneration without scarring. Science (New York, NY). 2021 372

18. Deng CC, Zhu DH, Chen YJ, Huang TY, Peng Y, Liu SY. et al. TRAF4 Promotes Fibroblast Proliferation in Keloids by Destabilizing p53 via Interacting with the Deubiquitinase USP10. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2019;139:1925-35.e5

19. Vu R, Jin S, Sun P, Haensel D, Nguyen QH, Dragan M. et al. Wound healing in aged skin exhibits systems-level alterations in cellular composition and cell-cell communication. Cell reports. 2022;40:111155

20. Salazar VS, Gamer LW, Rosen V. BMP signalling in skeletal development, disease and repair. Nature reviews Endocrinology. 2016;12:203-21

21. Deng CC, Zhang LX, Xu XY, Zhu DH, Cheng Q, Ma S. et al. Risk single-nucleotide polymorphism-mediated enhancer-promoter interaction drives keloids through long noncoding RNA down expressed in keloids. The British journal of dermatology. 2023;188:84-93

22. Dulauroy S, Di Carlo SE, Langa F, Eberl G, Peduto L. Lineage tracing and genetic ablation of ADAM12(+) perivascular cells identify a major source of profibrotic cells during acute tissue injury. Nature medicine. 2012;18:1262-70

23. Sobecki M, Chen J, Krzywinska E, Nagarajan S, Fan Z, Nelius E. et al. Vaccination-based immunotherapy to target profibrotic cells in liver and lung. Cell stem cell. 2022;29:1459-74.e9

24. Gomez-Puerto MC, Iyengar PV, García de Vinuesa A, Ten Dijke P, Sanchez-Duffhues G. Bone morphogenetic protein receptor signal transduction in human disease. The Journal of pathology. 2019;247:9-20

25. Plikus MV, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Ito M, Li YR, Dedhia PH, Zheng Y. et al. Regeneration of fat cells from myofibroblasts during wound healing. Science (New York, NY). 2017;355:748-52

26. Wang RN, Green J, Wang Z, Deng Y, Qiao M, Peabody M. et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) signaling in development and human diseases. Genes Dis. 2014 1

27. Distler JHW, Györfi AH, Ramanujam M, Whitfield ML, Königshoff M, Lafyatis R. Shared and distinct mechanisms of fibrosis. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2019;15:705-30

28. Correa-Gallegos D, Ye H, Dasgupta B, Sardogan A, Kadri S, Kandi R. et al. CD201(+) fascia progenitors choreograph injury repair. Nature. 2023;623:792-802

29. Correa-Gallegos D, Jiang D, Christ S, Ramesh P, Ye H, Wannemacher J. et al. Patch repair of deep wounds by mobilized fascia. Nature. 2019;576:287-92

30. Mochizuki S, Okada Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:621-8

31. Kveiborg M, Albrechtsen R, Couchman JR, Wewer UM. Cellular roles of ADAM12 in health and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1685-702

32. Loechel F, Fox JW, Murphy G, Albrechtsen R, Wewer UM. ADAM 12-S cleaves IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 and is inhibited by TIMP-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:511-5

33. Nikoloudaki G, Creber K, Hamilton DW. Wound healing and fibrosis: a contrasting role for periostin in skin and the oral mucosa. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2020;318:C1065-c77

34. Ontsuka K, Kotobuki Y, Shiraishi H, Serada S, Ohta S, Tanemura A. et al. Periostin, a matricellular protein, accelerates cutaneous wound repair by activating dermal fibroblasts. Experimental dermatology. 2012;21:331-6

35. Elliott CG, Wang J, Guo X, Xu SW, Eastwood M, Guan J. et al. Periostin modulates myofibroblast differentiation during full-thickness cutaneous wound repair. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:121-32

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Cheng-Cheng Deng, Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China. Email: dengchchedu.cn; or Bin Yang, Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China. Email: yangbin1edu.cn; or Zhili Rong, Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China. Email: rongzhiliedu.cn.

Corresponding authors: Cheng-Cheng Deng, Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China. Email: dengchchedu.cn; or Bin Yang, Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China. Email: yangbin1edu.cn; or Zhili Rong, Dermatology Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510091, China. Email: rongzhiliedu.cn.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact