10

Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(6):2774-2785. doi:10.7150/ijbs.121234 This issue Cite

Review

Pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts: a review

Department of Pharmaceutical Pathophysiology, Medical University of Gdańsk, Gdańsk, Poland.

Received 2025-7-8; Accepted 2025-12-27; Published 2026-2-18

Abstract

Pancreatic cancer is a very deadly disease, with no effective therapy currently employed in clinical practice, highlighting the urgent need for new therapeutic strategies. Cancer cells represent a minority within the pancreatic tumor, which is characterized by a pronounced stromal compartment. As fibrosis is characteristic of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the cell population of particular interest is the pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblast population, observed to be the main extracellular matrix producers. Recent studies revealed a plurality of myofibroblast functions in the pancreatic tumor, beyond their role in matrix secretion: they were noted to promote cancer cell proliferation and invasiveness in in vitro and in vivo studies, and have been described as potential prognostic biomarkers, along with stromal collagen content. Moreover, myofibroblasts were found in precancerous pancreatic lesions, and may thus be involved in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Paradoxically, depletion of myofibroblasts had detrimental effects on the outcome in an in vivo study, and their precise role in the disease remains unclear. This review summarizes for the first time studies on pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts, focusing on the origin, function, biomarker potential, and heterogeneity of these cells in the pancreatic tumor, aiming to elucidate their role in pancreatic cancer progression.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, myofibroblast, fibrosis, microenvironment, stellate cell, extracellular matrix

Background

The cellular portion of the tumor microenvironment consists of cells belonging to a number of cell types beyond cancer cells, including various immune cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts [1]. These cells perform a plurality of functions within the tumor, inducing (or inhibiting) angiogenesis, immune tolerance or cancer cell proliferation [1]. Microenvironment cells are also responsible for the secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which form the acellular portion of the microenvironment [1]. This phenomenon, dubbed “desmoplastic reaction”, furthers the pro-tumor effects of the microenvironment, inducing angiogenesis [2] or serving as a nutritional source for cancer cells [3]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are known as primary producers of ECM in tumors [4].

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a yet-unbeatable disease, a characteristic of which is its low 5-year survival rate [5]. Dense stroma is a characteristic of the pancreatic tumor [6], decreasing drug penetration and thus, diminishing therapy effectiveness [7]. As such, fibroblasts present within the tumor's microenvironment are of interest from both the clinical and biological perspective. Emerging evidence points to the presence of three main fibroblast types associated are distinguished in this disease: inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts, which are characterized by their low expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 [8]; antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts, which express HLA-II-group antigen-presenting molecules [9], and myofibroblasts, which produce the ECM constituents collagen I and hyaluronan, and are characterized by their high expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin [10,11]. Thus, myofibroblasts are a fibroblast population of crucial importance for the course of pancreatic cancer. The novelty of that classification leads to an unclear nomenclature used to describe fibroblasts in the tumor environment, as the name “myofibroblasts” was sometimes used to describe the overall cancer-associated fibroblast population in the tumor [12]. The different functions of cancer-associated fibroblast population in the pancreatic tumor warrant the application of the name “myofibroblasts” as strictly αSMA-high, ECM-producing cells with no interleukin signalling activation of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumor microenvironment, and this term is used in such this meaning in this review.

Despite the myofibroblast's role in desmoplastic reaction, depletion of these cells in the tumor also worsened the course of the disease [13]. Nevertheless, new studies show that the pro-cancer role of these cells is not limited to ECM formation, extending to enhancing cancer cell chemoresistance or proliferation, among others. Furthermore, myofibroblasts dominated the microenvironment of pre-cancerous, high-grade pancreatic lesions, suggesting a role in carcinogenesis [14]. This review summarizes current state of literature regarding cancer-associated myofibroblasts, and attempts to elucidate the source of the apparent ambiguity of the myofibroblasts' role in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment, in addition to describing their origins and heterogeneity.

Origins of pancreatic adenocarcinoma-associated myofibroblasts

Sources of pancreatic adenocarcinoma-associated myofibroblasts

The origins of myofibroblasts in pancreatic tumor microenvironment are currently unclear. There is evidence for pancreatic stellate cells forming myofibroblasts, myofibroblastic conversion of the in situ fibroblasts and for the bone marrow origin of myofibroblasts in the course of pancreatic cancer.

The pancreas contains fibroblast-like stellate cells, characterized by their high expression of vimentin, adipoliphilin and cytoglobin, and retinoid droplets content [15]. Under physiological conditions, these cells are quiescent and possibly exhibit only limited ECM remodelling functions, as they secrete metalloproteinases and their inhibitors [16]. However, growth factors or cytokines - such as may be released from the pancreatic tumor [17] - may activate them and subsequently decrease vimentin, cause loss of retinoid content in addition to triggering a large increase in αSMA expression [10,18,19]. Activated pancreatic stellate cells are able to proliferate [6], in addition to secreting ECM components such as collagens (type I, type III), laminin and fibronectin [10]. These traits, together with the aforementioned αSMA production, are characteristic to myofibroblasts [10]. A lineage-tracing study established that in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, stellate cell-derived myofibroblasts represent only a minor fraction (10% - 15%) of cancer-associated fibroblasts [20].

Bone marrow appears to also be a source of pancreatic stellate cells in mice, as found by Watanabe et al., who observed that 8 weeks post-transplantation, 8.7% of pancreatic stellate cells were donor-derived, and that induction of pancreatic fibrosis (concomitant with stellate cell activation) has resulted in that percentage being increased to over 20% [21]. Thus, bone marrow-derived cells may be concluded to be a source of stellate cells, which may transition into myofibroblasts during inflammation, and inflammation itself increases the amount of bone marrow-derived cells in the pancreas. While neither of these studies have tested pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumor, inflammation is directly related to pancreatic carcinogenesis [22].

There is a possibility of pancreatic fibroblast recruitment into the tumor and their subsequent activation. Fibroblasts were identified in the healthy human pancreas, differing from stellate cells by their lack of retinoid droplets. Medium conditioned by fibroblasts from an older person's pancreas was found to increase the growth rate of Panc10.05 and MIA-PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells, which was not observed when medium conditioned by a younger person's pancreatic fibroblasts was used [23]. Interestingly, the isolated fibroblasts were observed to express αSMA, suggesting a possibility of a spontaneous fibroblast activation during cell culture [24,25]. While that study shows that activated pancreatic fibroblasts exhibit a higher pro-tumor potential with aging, these cells may not be described as true myofibroblasts due to a lack of cancer cell-related signalling, essential for the development of myofibroblast phenotype [8], in the culture [23]. As the isolated fibroblasts were noted to express Gli-1 [23] - a transcription factor known to designate pancreatic fibroblast populations giving rise to pancreatic myofibroblasts [25] - these results may still be relevant for the role myofibroblasts in PDAC.

The adipose tissue is a known source of mesenchymal stem cells [26], which were observed to transform into the pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts and inflammatory fibroblasts in vitro upon coculture with pancreatic cancer cells and later determined to secrete a cancer cell motility-enhancing ECM when exposed to pancreatic cancer cell-conditioned medium [26]. Endothelial cells proximal to the tumor are also a known source of fibroblasts in various cancers, including PDAC [27-29], differentiating into fibroblasts upon stimulation with TNF-α [29]. These endothelial-derived fibroblastic cells were noted to have ECM-secretory capabilities [29], proving that they may form a part of the myofibroblastic subpopulation of CAFs in PDAC.

Gao, Li, Cheng et al. conducted a single-cell study of several different malignant tumors, including pancreatic cancer tumors. They have established the pericyte or smooth muscle cell origin of the terminally-differentiated myofibroblasts, noting an abundance of likely pericyte-derived myofibroblasts in pancreatic tumors; the less-differentiated myofibroblasts were described as originating from other cell types, predominantly normal fibroblasts [30].

Molecular pathways and spatial signalling driving myofibroblast differentiation in PDAC

Various molecular pathways appear to have been implicated in the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. TGFβ, produced by many different types of cells in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment, including pancreatic stellate cells, cancer cells and immune cells [30], is a known inducer of differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts [31,32]. While tumor αSMA and collagen levels decrease upon inhibition of fibroblast TGFβ receptor in a mouse model study [32], it was found that such an inhibition decreases the overall tumor fibroblast count and does not deplete myofibroblasts [33]. The proportion of myofibroblasts within the cancer microenvironment was observed to be further regulated by IL-1 signalling, which drives the differentiation of cancer-associated fibroblasts to inflammatory fibroblasts, underscoring the importance of interplay between IL-1 and TGFβ signalling in cancer-associated fibroblast differentiation [32]. An important signal transducer in TGFβ-driven fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition appears to be the NOX4 reactive oxygen species-generating activity induced by TGFβ: the reactive oxygen species cause DNA damage, which in turn activates the ATM kinase [34-36]. Blocking reactive oxygen species production by treatment with an anti-oxidant or NOX4 inhibitor after TGFβ treatment was found to decrease the number of myofibroblasts within the tumor and prevent cancer associated fibroblasts from transitioning to myofibroblasts [37]. Similarly, inhibiting ATM concurrently to TGFβ treatment was similarly observed to inhibit differentiation of cancer-associated fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and to somewhat revert myofibroblasts back to fibroblast phenotype, evident by the decrease in αSMA, collagen I and fibronectin expression in the cells [35]. Importantly, it has been reported that the ATM can also transduce reactive oxygen species-related signal independently of DNA damage [36]. However, no study of whether reactive oxygen species-related DNA damage is required for ATM activation and subsequent DNA damage has been conducted.

There is evidence for PI3K/Akt/MAPK pathway involvement in pancreatic stellate cell activation to myofibroblasts, as decreasing the PI3K inhibitor PTEN expression increased collagen synthesis and motility of these cells, while increasing PTEN expression increased stellate cell apoptosis rate [38]. Moreover, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is established to be involved in fibroblast activation in PDAC [38], inducing their proliferation by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway [39], further proving its importance in myofibroblast biology.

The Smoothened receptor signalling was also found to be overexpressed by isolated human pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts (but not by normal pancreatic fibroblasts); the activation of this receptor resulted in an increase in Gli-1, reversed upon knockdown of Smoothened's gene [40]. Inhibition of Smoothened has resulted in a decreased tumor growth and myofibroblast number coupled with an increased number of inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts in an animal model study of pancreatic cancer [41].

Protein kinase N2 is also thought to be important for the activation of stellate cells and their transformation to myofibroblasts: in mouse pancreatic stellate cells, deletion of the PKN2 gene, coding for said kinase, resulted in an increased lipid storage by the stellate cells and a decreased number of αSMA fibres in the cells, apparent even after their stimulation with tumor-growth factor 1 (TGFβ1) [42], proving that the signalling from this kinase is important for maintenance of myofibroblast identity. However, the authors did not observe a decreased tumor collagen level in an orthotopic animal model bearing a knockout-PKN2. It appears that the ECM-secretory aspect of myofibroblasts is controlled independently of this kinase through the mTOR/4E-BP1 pathway, as its inhibition with a somatostatin analogue resulted in reduction of fibrosis and subsequent sensitization of the tumor to gemcitabine [43].

Sun et al. reported a significant role of tumor-associated macrophages in pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblast formation: the cytokine IL-33 is secreted by inflammatory fibroblast population, activating the ST2 receptor on the macrophages. Signal is transduced further by ERK and MYC, stimulating the macrophages to produce CXCL3. This in turn subsequently activates the fibroblast CXCR2 receptor, triggering the fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition; inhibiting the ST2 receptor has decreased the level of αSMA in tumor tissues [44].

A 2017 coculture study suggested that direct contact between cancer cells and stellate cells promoted differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts [8]. However, subsequent work demonstrated that this contact is not strictly required; rather, proximity to cancer cells and exposure to short-range paracrine cues, particularly TGFβ, are sufficient to induce the myofibroblast phenotype. In contrast, fibroblastic cells located farther from tumour cells experience IL-1α/TGFβ-driven activation of the JAK/STAT pathway, giving rise to inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts that secrete cytokines such as IL-6 and CXCLs [32]. The importance of spatial signalling molecule gradients was corroborated by a coculture study of adipose-derived stem cells (which transformed into fibroblasts) and pancreatic cancer cells [26]. Thus, spatial organization and competing TGFβ versus IL-1/JAK/STAT signals determine CAF subtype specification.

Heterogeneity

Recent research established that not only are there various populations of fibroblasts found within the pancreatic tumor, but there is also a considerable heterogeneity within the pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts. While different marker molecules were noted to distinguish different myofibroblast subpopulations, there is no single, unified classification of these cells into subtypes.

Two patient-derived myofibroblast cell lines were also examined for heterogeneity. It had been revealed that they varied by the expression of (myo)fibroblast markers, with one cell line expressing FAP and PDGFR-α at a considerably lower rate than another. The “expression-low” myofibroblasts-conditioned medium was observed to significantly increase proliferation of patient-derived pancreatic cancer cells, while the “expression-high” cells-conditioned medium did not influence cancer cell proliferation, but decreased their migration [45]. This points to the possible distinction between the myofibroblast subpopulations in terms of their influence on pancreatic cancer cells. However, as only two patient-derived myofibroblast cell lines were studied, no firm conclusion may be drawn.

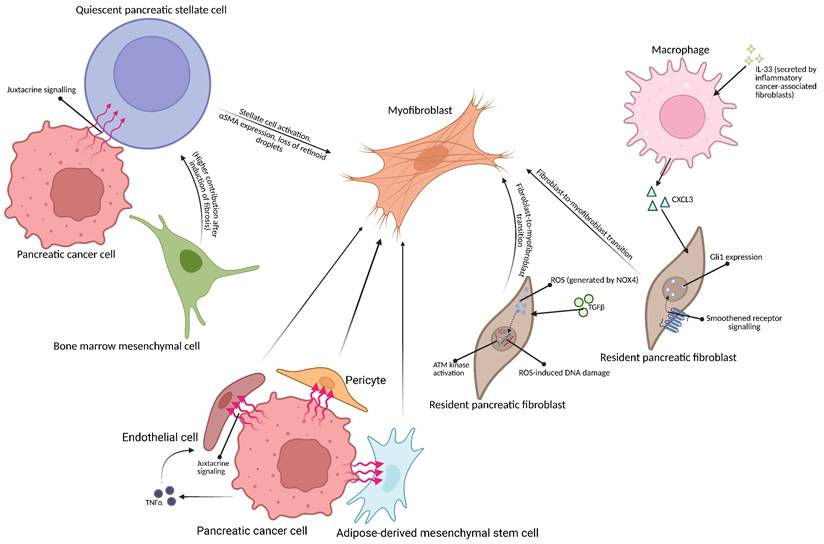

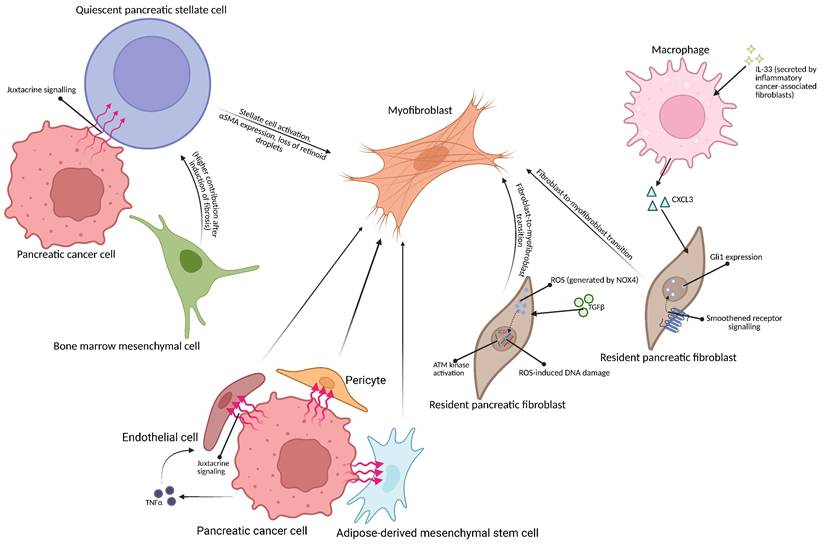

Schematic representation of possible origins of myofibroblasts in pancreatic tumor microenvironment. (Top left) Pancreatic cancer cell may activate the pancreatic stellate cell via juxtacrine means [8]. The bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cell may differentiate into a quiescent pancreatic stellate cell [21], becoming activated by signalling from the cancer cell [8]. (Right) Inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblast-secreted IL-33 causes macrophages in the tumor microenvironment to secrete CXCL3, causing fibroblast-to myofibroblast transition [44]; TGFβ1 may also trigger fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition in Gli-1-expressing fibroblasts [40]. (Bottom) Endothelial cells, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and pericytes may also be transformed into myofibroblasts due to signalling from pancreatic cancer cells [26,29,30]. Created with BioRender.com

Mucciolo et al. have observed two distinct pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts subpopulations, differing by the presence of CD90. The CD90+ myofibroblasts appear to be mainly responsible for ECM production, as they were observed to have an increased expression of ECM-related genes. They also expressed myofibroblast markers Acta2 and Col1a1 at a higher rate than CD90- cells, which had a higher expression of EGFR signalling-related genes and of secreted, metastasis-promoting proteins, such as Spp1 and Sema3e [51], which was consistent with the observation that these myofibroblasts drive metastasis. The notion that there are two subtypes of myofibroblasts, with one of them being the primary producer of ECM, may explain the mechanism behind the emergence of collagen-high stromal type in pancreatic cancer [49]: possibly, a collagen-high ECM is formed due to there being more CD90+ myofibroblasts in the early part of carcinogenesis. Importantly, precise functions of these myofibroblast subpopulations were not determined; an animal model xenograft experiment using pancreatic cancer cells and either CD90+ or CD90- myofibroblasts could be conducted to shed light on this subject.

A yet another subset of myofibroblasts are the senescent myofibroblasts which were observed to occur in the vicinity of tumor ducts. Their presence caused a shift of macrophage phenotype from the anti-cancer M1 to the pro-cancer M2 phenotype. Moreover, these myofibroblasts increase in number as the disease progresses, demonstrating a possible senescence induction by the tumor [50]. Whether the presence of such myofibroblasts is a cause of disease progression, or the tumor cells induce senescence in myofibroblasts as the disease progresses is currently unknown.

Functions

Myofibroblasts in cancer cell regulation

Myofibroblasts are thought to be responsible for a number of pancreatic cancer-related processes (Figure 2), including promoting tumor invasiveness or secreting the ECM. It is currently understood that pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts also perform various other functions within the pancreatic tumor. A portion of myofibroblasts stimulated by TGFβ treatment was noted to secrete an EGFR ligand - amphiregulin - in an autocrine fashion. Such EGFR-activated myofibroblasts were observed to stimulate epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cancer cells and increase their invasiveness in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer [51].

Conversely to the above, a mouse model study of pancreatic cancer using the human CAPAN-1 cell line injected alone or together with human myofibroblasts isolated from metastatic sites of pancreatic cancer demonstrated that the myofibroblasts confer an increase in invasiveness onto the cancer cells [46]. Whether this effect would also be observed with myofibroblasts isolated from the primary tumor is unknown. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that myofibroblasts may transition into inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts and secrete pro-invasive cytokines, such as interleukin 6 [8,47]. Thus, it is impossible to ascribe the effects of myofibroblast co-injection as occurring solely due to the presence of myofibroblasts.

Cultured mouse stellate cells were also noted to express Zeb1 [52], a transcription factor commonly understood to be the main regulator of the EMT [53]. However, its function was demonstrated to be different in these cells, as it was observed regulate to fibroblast survival and proliferation. Zeb1 knockdown in the stellate cells was observed to decrease collagen I, metalloproteinase 9, and αSMA genes expression levels in activated pancreatic stellate cells, similarly to Zeb1 haploinsufficiency, which has also caused a decrease in ECM-related, but not in αSMA, gene expression, indicating the importance of Zeb1 in pancreatic stellate cell activation and subsequent desmoplastic reaction. Notably, wild-type activated stellate cell-conditioned medium was more effective than Zeb1-haploinsufficient activated stellate cells-conditioned medium at promoting mouse pancreatic cancer cell migration and proliferation. Moreover, a higher activity of Ras in cells derived from mouse pancreatic tumors bearing mutated KRAS gene (a known oncogene, often implicated in pancreatic cancer carcinogenesis) was noted when they were cultured in a wild-type activated stellate cells-conditioned medium, and, to a lesser extent, in a Zeb1-haploinsufficient wild type conditioned medium [52]. As Zeb1-haploinsufficient mice bearing pancreas-specific KRAS mutation developed pancreatic tumors much more slowly than mice with both alleles of Zeb1 active, and the Ras GTPase requires an external activator [54], it was concluded that the Zeb1 transcription factor controls the secretome of stellate cells-derived myofibroblasts in such a way that they promote disease progression by increasing the Ras activity of the pancreatic cancer cells with mutated KRAS [52]. The results of this study should be interpreted cautiously, however, as no cancer cell-stellate cell coculture experiment was performed [52], and thus, no cancer cell-related signalling required for myofibroblast development [8] was present and the resultant activated stellate cells do not really represent myofibroblasts as claimed by the title. Importantly, hypoxia, a known characteristic of PDAC [55], was also noted to increase pancreatic stellate cells' pro-tumor functions by increasing cancer cell invasiveness by secreting connective tissue growth factor [56].

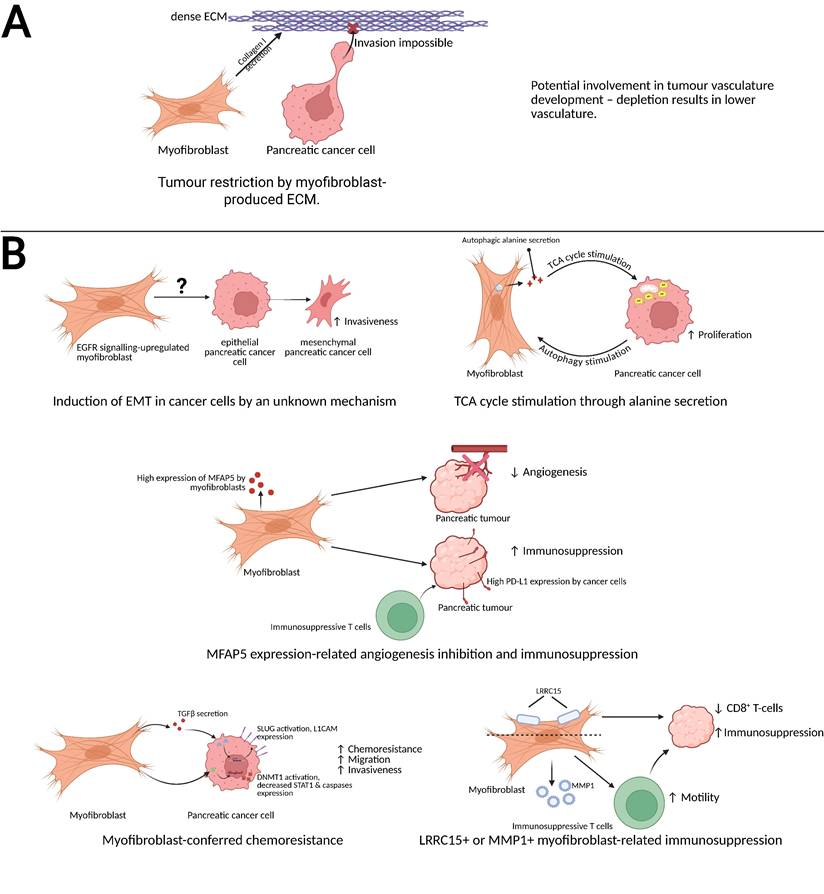

Schematic representation of the anti-cancer and pro-cancer functions of pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts. (A) Myofibroblast-secreted collagen I serves as an obstacle for pancreatic cancer cell invasiveness [70] and potentially is involved in tumor vasculature development [13]. (B, top left) EGFR-upregulated myofibroblasts induce the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells, increasing their invasiveness [51]. (B, top right) Myofibroblasts secrete alanine, a product of their autophagic turnover, which stimulates the pancreatic cancer cell's TCA cycle, increasing energy production and proliferation rate [59]. (B, centre) MFAP5-expressing myofibroblasts inhibit tumor angiogenesis create immunosuppressive microenvironment by inducing PDL-1 expression in cancer cells and causing immunosuppressive T cell recruitment [62]. (B, bottom left) Myofibroblasts secrete TGFβ, which causes the cancer cell to express SLUG and L1CAM, and activate pancreatic cancer cell's DNMT1, which causes a decreased expression of STAT1 and caspases; these processes result in an increased migration rate, chemoresistance and invasiveness [57,58]. (B, bottom right) Similarly, LRRC15+ myofibroblasts and MMP1+ myofibrobroblasts create an immunosuppressive microenvironment in PDAC [30,64]. Created with BioRender.com

A coculture experiment of pancreatic cancer cells or normal pancreatic duct epithelial cells with myofibroblasts has revealed a decrease in the expression of STAT1, subsequently decreasing the expression of caspases through an increased methylation of the STAT1 promoter by DNMT1 [57]. Moreover, a mouse model study revealed that when the myofibroblasts and T3M4 pancreatic cancer cells were co-injected into mice, the developed tumor was found to be resistant to etoposide, in addition to exhibiting a decreased expression of caspases and a more pronounced stroma [57]. While inhibition of DNMT1 expression was performed in vitro and determined to sensitise the cells to etoposide therapy, a similar experiment has not been performed in the animal experiment phase of the study. As such, the mechanism behind that myofibroblast-conferred chemoresistance is unknown; it may be hypothesised to be related to aforementioned STAT1 inhibition, but can also be effect of dense stroma formation in the co-injected tumors, which could decrease drug penetration [7]. Schäfer et al. observed that coculturing the normal pancreatic duct cells with pancreatic myofibroblasts also increases cell migration, invasiveness and chemoresistance through induction of L1CAM expression in the cells via the action of myofibroblast-secreted TGFβ on pancreatic cell's Slug [58]. Overall, myofibroblasts may be understood to drive the carcinogenesis of pancreatic duct cells through increasing their chemoresistance and invasiveness.

Another process through which myofibroblasts may support pancreatic cancer cells is alanine secretion. Activated pancreatic stellate cells cocultured with PDAC cells were noted to produce it via autophagy, stimulated by pancreatic cancer cells. In turn, secreted alanine was observed to stimulate proliferation of the cancer cells by stimulating TCA cycle after its conversion to pyruvate. This effect was also observed in vivo, with autophagy inhibition decreasing tumor growth rate and increasing survival in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer [59], underscoring the significance of autophagy within myofibroblasts for pancreatic tumor growth.

Myofibroblasts in pancreatic tumor microenvironment remodelling

Myofibroblasts' main function is established to be the production of ECM components - collagens (I, III), laminin and fibronectin - during pancreatic damage, including pancreatic neoplasm [6,10]. This phenomenon, dubbed desmoplastic reaction, is a major obstacle in pancreatic cancer treatment, as the dense stroma surrounding the tumor decreases the drug penetration into the tumor [60,62], Despite that, attempts at ameliorating the disease by either depleting pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts or lowering their collagen expression resulted in a worsened outcome and increased invasiveness [13,61]. Similarly, the deletion of PKN2 gene impaired the activation of mouse stellate cells upon TGFβ treatment and resulted in an increase in the inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblast phenotype, increased cancer cell invasiveness and a decreased survival in an animal study [42]. This shows a dual, paradoxical role of myofibroblasts and ECM in pancreatic cancer: despite the known pro-cancer influence of these cells, they appear to simultaneously lower cancer invasiveness.

Besides desmoplasia, myofibroblasts were also noted to increase the level of immune-suppressing cells in the tumor stroma. In the tumor microenvironment, they were observed to be the main (although not the only) MFAP5-expressing cell type. The expression of this protein was correlated with worse prognosis, and knockdown experiments revealed that its expression is responsible for conferring increased migratory and invasive capabilities onto the pancreatic cancer cells, in addition to promoting the EMT in cancer cells and decreasing the tube-formation capability of HUVEC cells. These findings were recapitulated in a xenografted mouse model of pancreatic cancer. The proportion of immunosuppressive Treg and myeloid-derived Ly6G+ cells in the tumor was also decreased upon the knockdown of MFAP5 [62]. Moreover, the MFAP5-expressing fibroblasts were noted to secrete increased amount of hyaluronic acid and CXCL10, a cytokine which stimulated cancer cells to produce immunosuppressive PD-L1 [62,63]; knockdown of MFAP5 in fibroblasts was observed to sensitise the cancer to anti-PD-L1 immune therapy [62]. Thus, MFAP5 may be understood as a main promoter of myofibroblasts' pro-cancer effects. Curiously, despite the observed inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by MFAP5-expressing myofibroblasts, depletion of myofibroblasts was also noted to decrease pancreatic tumor vascularity [13]. It is possible that while the presence of MFAP5-expressing myofibroblasts inhibits the angiogenesis, there also exists a different, unidentified myofibroblast population, which supports angiogenesis, or that the ECM secretion is actually necessary for proper vasculature development. Curiously, even just decreasing the expression of collagen I in the myofibroblasts has resulted in an accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the stroma [61], indicating a connection between myofibroblasts, the ECM and immune suppression in pancreatic cancer.

The presence of LRRC15 protein was also observed to denote an immune-suppressing myofibroblast subpopulation: TGFβR2 signalling activation in non-differentiated fibroblasts leads to the creation of LRRC15+ myofibroblasts, which form the most abundant fibroblast-related cell population within the pancreatic cancer microenvironment, as observed during an animal study. Depletion of that subset of myofibroblasts led to tumor growth rate inhibition due to an improvement in cytotoxic T CD8+ function. Moreover, LRRC15+ myofibroblasts-depleted tumors were more susceptible to anti-PDL-1 therapy [64]. Thus, the presence of LRRC15 may denote a subset of myofibroblasts related to immune suppression. However, as the majority of cancer-associated myofibroblasts express this marker, it is possible that there are multiple LRRC15+ subpopulations, and depletion of myofibroblasts expressing this marker merely coincidentally results in anti-tumor effects. A single-cell transcriptomics study revealed that LRRC15+ cells represent the end stage of differentiation of a cell into the myofibroblast [30]. MMP1-expressing myofibroblasts were also noted to be inducers of immune suppression in the pancreatic tumor, as they increased Treg migration upon coculture and were found, together with the LRRC15+ myofibroblasts, to be more numerous in tumors of patients which did not respond to immune therapy [30].

Hutton et al. have found a way to divide the population of pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts based on their expression of CD105 into a CD105+ immune-suppressive subset and a CD105- immune-promoting fibroblasts. However, the expression of these markers was not confined to just myofibroblasts but to all pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts [65]. Fibroblastic cells in PDAC interact with a number of other cell types besides the cancer cells and immune cells: pancreatic stellate cells may control angiogenesis in PDAC as they secrete both pro-angiogenic hepatocyte growth factor [66] and vascular endothelial growth factor [67] and increase the cancer cells' production of anti-angiogenic endostatin [67]. They may also promote perineural invasion [68]. However, none of these effects has been ascribed specifically to the myofibroblast subpopulation.

Myofibroblasts as prognostic biomarkers

As myofibroblasts are identified in both high-grade precancerous lesions [14] and pancreatic cancer tumor [8,46], it appears that their emergence may either result in formation of pancreatic cancer, or at least be correlated with the disease's occurrence. Notably, myofibroblasts' influence on the prognosis of pancreatic cancer is controversial: it was once thought that a high αSMA-to-collagen ratio (and thus, a high proportion of myofibroblasts in the tumor's microenvironment) is associated with a worse outcome in pancreatic cancer patients [48], while a later study found that, for post-neoadjuvant therapy patients, a high proportion of myofibroblasts observed post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with a favourable outcome in patients treated with a neoadjuvant therapy, but not in patients who undergone resection without neoadjuvant therapy, for whom the low αSMA-to-collagen ratio was correlated with an increased survival [69]. This demonstrates the possible significance of myofibroblasts for the efficiency of said therapy.

Yet another approach identified three stroma subtypes: αSMA-rich, FAP-rich and collagen-rich, with the last of these types being characterized by a significantly higher overall survival, while the αSMA-rich stroma was correlated with the lowest survival probability [49]. This may further reinforce the notion that fibrous stroma is detrimental to pancreatic cancer progression, and that myofibroblasts are pro-tumor elements of pancreatic cancer stroma. Despite myofibroblasts being the main producers of collagen, surface of αSMA-stained areas did not correlate with stromal collagen content [49]. As inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts are also known to express αSMA (though generally at a lower level than cancer-associated myofibroblasts) [32], it is possible that the αSMA-low collagen-high type of pancreatic cancer stroma is composed of highly ECM-secretory myofibroblasts, while the collagen-low αSMA-high type is composed predominantly of inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts [8] and CD90- myofibroblasts [51]. A high level of collagen may then restrict cancer progression [70], while a high level of inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts may enhance cancer progression by the secretion of pro-cancer cytokines [8].

The origin of myofibroblasts may also serve as a prognostic factor: pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts of stellate cell origin are known to possess a unique ECM-related expression profile that increases ECM stiffness and the level of tumor the focal adhesion kinase signalling [20]. That specific expression signature was correlated with a lowered patient survival [20]. The possible mechanism through which the pancreatic stellate cells-derived myofibroblasts are associated with the disease outcome is unclear, but an observed post-depletion slight decrease in myeloid cell number within the tumor [20] may indicate that the activated pancreatic stellate cell-derived ECM serves as a niche for recruited immune cells, which then support the tumor. This is corroborated by a study by Wu et al., who observed a greater efficiency of drug delivery to the tumor after inducing pancreatic stellate cells quiescence [71]. Overall, the result suggests that a high activity of pancreatic stellate cells-derived myofibroblasts worsens the outcome of the disease.

Based on the above, two myofibroblast-related prognostic biomarkers may be postulated. First, a low level of αSMA coupled with a high level of collagen in the pancreatic tumor, possibly indicating a predominance of ECM-producing myofibroblasts in the stroma, is indicative of a favourable prognosis. Second, a high number of myofibroblasts of stellate cell origin, possessing a specific ECM-secretory signature, is indicative of an unfavourable prognosis. Both of these potential biomarkers must be validated in clinical trials.

Conclusions

Myofibroblasts are known to constitute a significant fraction of pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblast population [8]. Several studies explain the origins of these cells, which includes transition from pancreatic stellate cells, development from bone marrow-derived progenitors, and activation of in situ fibroblasts. Importantly, both fibroblast and pancreatic stellate cell activation is caused by episodes of pancreatic damage (such as inflammation) and leads to them assuming a myofibroblast phenotype [18].

Mechanistically, the most important molecular pathway for fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition is the TGFβ-NOX4-ATM kinase pathway, with Smoothened receptor signalling, PI3K/AKT/MAPK pathway signalling, mTOR activity and PKN2 also described as relevant for myofibroblast phenotype attainment and maintenance [34,35,43]. Tumor-associated macrophages also play a role in fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition via the IL-33-ST2-CXCR2 axis [44].

While the aforementioned pathways present as attractive potential therapeutic targets, as decreasing the myofibroblast count could lead to a decreased fibrosis, and thus, to a higher drug penetration, it is important to note that attempting to decrease desmoplasia did not result in a better outcome in a clinical setting [72], and a total depletion of myofibroblasts worsens the disease's outcome [14,61,64]. This may be due to a lack of mechanical barrier of collagen post-depletion, as it is known to hinder cancer cell invasion [70]. Targeting only a subset of myofibroblasts expressing a specific marker instead could be a viable strategy. For example, depletion of LRRC15+ fibroblasts (expressed by the majority of them) was observed to result in a higher anti-tumor activity of CD8+ T cells and sensitize the tumor to immune therapy [64]. Similarly, CD90- myofibroblasts were noted to promote cancer cell metastasis, likely via secretion of pro-metastatic factors [49]. These findings suggest that therapeutic modulation, rather than blanket elimination, may unlock the full clinical potential of targeting myofibroblasts.

Considerable research has been conducted aiming to determine contributions of different myofibroblast subpopulations to pancreatic adenocarcinoma: besides the above-mentioned LRRC15+ myofibroblast subpopulation, MFAP5+, MMP1+ and senescent myofibroblasts were implicated in immune suppression [30,50,62], while CD90- and amphiregulin-secreting myofibroblasts were implicated in enhancing cancer cell proliferation or invasiveness [51]. Stellate cell-derived pancreatic cancer-associated myofibroblasts are of a high-importance as their secretory phenotype was correlated with a worse outcome [20]. Table 1. summarizes the described subpopulations of myofibroblasts in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. While these aforementioned subpopulation studies provide a possible clinical targets for PDAC management, a possible different approach, consisting of treating all cancer-associated fibroblasts as a spectrum and forming “functional units” together with the ECM instead of attempting to isolate specific subpopulations has recently been described by Francescone et al. [73].

Myofibroblast subpopulations in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and their functions.

| Subpopulation | Function | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| LRRC15+ | Immune suppression | Possibly represents the most-differentiated myofibroblasts of pericyte origin | [30,64] |

| MFAP5+ | Immune suppression, angiogenesis | - | [62] |

| MMP1+ | Immune suppression | Enhance Treg motility, correlated with worse immune therapy outcome | [30] |

| Senescent | Immune suppression | Increase in number with disease progression | [50] |

| CD90- | Increase of cancer cell invasiveness | - | [51] |

| CD90+ | ECM secretion | - | [51] |

| Autocrine amphiregulin-secreting | Stimulation of EMT, increase of cancer cell invasiveness | - | [51] |

| Stellate-cell derived | ECM secretion | Unique secretory signature correlated with worse outcome | [20] |

Looking forward, the heterogeneity of myofibroblasts remains a central obstacle in pancreatic cancer. Utilizing high-throughput single-cell approaches will be essential for the full appreciation of distinct myofibroblast subtypes. By shifting the focus from elimination to modulation, future therapeutic strategies may improve drug delivery and overcome chemotherapeutic resistance by disrupting the pro-tumor functions of these cells.

Abbreviations

αSMA: Alpha-smooth muscle actin; ATM: Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (kinase); CD90: Cluster of Differentiation 90 (Thy-1 cell surface antigen); CXCL3: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 3; CXCL10: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10; DNMT1: DNA methyltransferase 1; ECM: Extracellular matrix; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; FAP: Fibroblast activation protein; Gli-1: Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1; HLA-II: Human leukocyte antigen class II; HUVEC: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells; IL-1: Interleukin 1; IL-6: Interleukin 6; IL-10: Interleukin 10; IL-33: Interleukin 33; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; L1CAM: L1 cell adhesion molecule; LRRC15: Leucine-rich repeat containing 15; MFAP5: Microfibril-associated protein 5; MIA-PaCa-2: Human pancreatic cancer cell line; MYC: Myelocytomatosis oncogene; NOX4: NADPH oxidase 4; PDGF: Platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR-α: Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha; PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1; PKN2: Protein kinase N2; PSC: Pancreatic stellate cell; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SLUG: Zinc finger protein SNAI2; SOX9: SRY-box transcription factor 9; STAT1: Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; ST2: Suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (IL-33 receptor); TCA cycle: Tricarboxylic acid cycle; TGFβ: Transforming growth factor beta; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; Zeb1: Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was supported by National Science Centre, OPUS 18 2019/35/B/NZ7/04212.

Author contributions

MB has collected and analysed myofibroblast-related studies, interpreted them and drafted the manuscript; IIS interpreted them and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Anderson NM, Simon MC. The tumor microenvironment. Current Biology. 2020;30(16):R921-5

2. Tlsty TD, Coussens LM. Tumor stroma and regulation of cancer development. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:119-50

3. Rainero E. Extracellular matrix internalization links nutrient signalling to invasive migration. Int J Exp Pathol. 2018;99(1):4-9

4. Liu T, Zhou L, Li D, Andl T, Zhang Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts build and secure the tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2019;7:60

5. Bengtsson A, Andersson R, Ansari D. The actual 5-year survivors of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on real-world data. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16425

6. Apte M V, Park S, Phillips PA, Santucci N, Goldstein D, Kumar RK. et al. Desmoplastic Reaction in Pancreatic Cancer Role of Pancreatic Stellate Cells. Pancreas. 2004;29(3):179-87

7. Sato H, Hara T, Meng S, Tsuji Y, Arao Y, Saito Y. et al. Multifaced roles of desmoplastic reaction and fibrosis in pancreatic cancer progression: Current understanding and future directions. 2023; 114(9): 3487-95.

8. Öhlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M. et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2017;214(3):579-96

9. Elyada E, Bolisetty M, Laise P, Flynn WF, Courtois ET, Burkhart RA. et al. Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discovery. 2019;9:1102-23

10. Bachem MG, Schneider E, Groß H, Weidenbach H, Schmid RM, Menke A. et al. Identification, Culture, and Characterization of Pancreatic Stellate Cells in Rats and Humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:421-32

11. Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A. et al. Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68(3):918-26

12. De Wever O, Van Bockstal M, Mareel M, Hendrix A, Bracke M. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts provide operational flexibility in metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;25:33-46

13. Özdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, Zheng X, Wu CC, Simpson TR. et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):719-34

14. Bernard V, Semaan A, Huang J, Anthony San Lucas F, Mulu FC, Stephens BM. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of pancreatic cancer precursors demonstrates epithelial and microenvironmental heterogeneity as an early event in neoplastic progression. Clinical Cancer Research. 2019;25(7):2194-205

15. Nielsen MFB, Mortensen MB, Detlefsen S. Identification of markers for quiescent pancreatic stellate cells in the normal human pancreas. Histochem Cell Biol. 2017;148(4):359-80

16. Phillips PA, Mccarroll JA, Park S, Wu MJ, Pirola R, Korsten M. et al. Rat pancreatic stellate cells secrete matrix metalloproteinases: implications for extracellular matrix turnover. Gut. 2003;52(2):275-82

17. Bachem MG, Zhou S, Buck K, Schneiderhan W, Siech M. Pancreatic stellate cells—role in pancreas cancer. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2008;393(6):891-900

18. Apte M V, Haber PS, Darby SJ, Rodgers SC, McCaughan GW, Korsten MA. et al. Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: Implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 1999;44(4):534-41

19. Mews P, Phillips P, Fahmy R, Korsten M, Pirola R, Wilson J. et al. Pancreatic stellate cells respond to inflammatory cytokines: Potential role in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;50(4):535-41

20. Helms EJ, Berry MW, Chaw RC, Dufort CC, Sun D, Onate MK. et al. Mesenchymal Lineage Heterogeneity Underlies Nonredundant Functions of Pancreatic Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Discovery. 2022;12(2):484-501

21. Watanabe T, Masamune A, Kikuta K, Hirota M, Kume K, Satoh K. et al. Bone marrow contributes to the population of pancreatic stellate cells in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297(6):1138-46

22. Hausmann S, Kong B, Michalski C, Erkan M, Friess H. The Role of Inflammation in Pancreatic Cancer. 2014; 816: 129-51.

23. Zabransky DJ, Chhabra Y, Fane ME, Kartalia E, Leatherman JM, Huser L. et al. Fibroblasts in the Aged Pancreas Drive Pancreatic Cancer Progression. Cancer Res. 2024;84(8):1221-36

24. Baranyi U, Winter B, Gugerell A, Hegedus B, Brostjan C, Laufer G. et al. Primary human fibroblasts in culture switch to a myofibroblast-like phenotype independently of TGF beta. Cells. 2019;8(7):721

25. Garcia PE, Adoumie M, Kim EC, Zhang Y, Scales MK, El-Tawil YS. et al. Differential Contribution of Pancreatic Fibroblast Subsets to the Pancreatic Cancer Stroma. CMGH. 2020;10(3):581-99

26. Miyazaki Y, Oda T, Mori N, Kida YS. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts in vitro. FEBS Open Bio. 2020;10(11):2268-81

27. Potenta S, Zeisberg E, Kalluri R. The role of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer progression. British Journal of Cancer. 2008;99(9):1375-9

28. Zeisberg EM, Potenta S, Xie L, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Discovery of Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition as a Source for Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007;67(21):10123-8

29. Adjuto-Saccone M, Soubeyran P, Garcia J, Audebert S, Camoin L, Rubis M. et al. TNF-α induces endothelial-mesenchymal transition promoting stromal development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cell Death & Disease. 2021;12(7):649

30. Gao Y, Li J, Cheng W, Diao T, Liu H, Bo Y. et al. Cross-tissue human fibroblast atlas reveals myofibroblast subtypes with distinct roles in immune modulation. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(10):1764-1783.e10

31. Stylianou A, Gkretsi V, Stylianopoulos T. Transforming growth factor-β modulates pancreatic cancer associated fibroblasts cell shape, stiffness and invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2018;1862(7):1537-46

32. Biffi G, Oni TE, Spielman B, Hao Y, Elyada E, Park Y. et al. Il1-induced Jak/STAT signaling is antagonized by TGFβ to shape CAF heterogeneity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(2):282-301

33. Qiang L, Hoffman MT, Ali LR, Castillo JI, Kageler L, Temesgen A. et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β Blockade in Pancreatic Cancer Enhances Sensitivity to Combination Chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(4):874-890.e10

34. Liu RM, Desai LP. Reciprocal regulation of TGF-β and reactive oxygen species: A perverse cycle for fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015;6:565-77

35. Mellone M, Piotrowska K, Venturi G, James L, Bzura A, Lopez MA. et al. ATM Regulates Differentiation of Myofibroblastic Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Can Be Targeted to Overcome Immunotherapy Resistance. Cancer Res. 2022;82(24):4571-85

36. Ditch S, Paull TT. The ATM protein kinase and cellular redox signaling: Beyond the DNA damage response. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2012;37:15-22

37. Hanley CJ, Mellone M, Ford K, Thirdborough SM, Mellows T, Frampton SJ. et al. Targeting the Myofibroblastic Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Phenotype Through Inhibition of NOX4. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(1):109-20

38. Cannon A, Thompson CM, Bhatia R, Armstrong KA, Solheim JC, Kumar S. et al. Molecular mechanisms of pancreatic myofibroblast activation in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2021;56(8):689-703

39. McCarroll JA, Phillips PA, Kumar RK, Park S, Pirola RC, Wilson JS. et al. Pancreatic stellate cell migration: role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67(6):1215-25

40. Walter K, Omura N, Hong SM, Griffith M, Vincent A, Borges M. et al. Overexpression of smoothened activates the Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(6):1781-9

41. Steele NG, Biffi G, Kemp SB, Zhang Y, Drouillard D, Syu LJ. et al. Inhibition of hedgehog signaling alters fibroblast composition in pancreatic cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2021;27(7):2023-37

42. Murray ER, Menezes S, Henry JC, Williams JL, Alba-Castellón L, Baskaran P. et al. Disruption of pancreatic stellate cell myofibroblast phenotype promotes pancreatic tumor invasion. Cell Rep. 2022;38(4):110227

43. Duluc C, Moatassim-Billah S, Chalabi-Dchar M, Perraud A, Samain R, Breibach F. et al. Pharmacological targeting of the protein synthesis mTOR /4E- BP 1 pathway in cancer-associated fibroblasts abrogates pancreatic tumour chemoresistance. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7(6):735-53

44. Sun X, He X, Zhang Y, Hosaka K, Andersson P, Wu J. et al. Inflammatory cell-derived CXCL3 promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis through a novel myofibroblast-hijacked cancer escape mechanism. Gut. 2022;71(1):129-47

45. Kearney JF, Trembath HE, Chan PS, Morrison AB, Xu Y, Luan CF. et al. Myofibroblastic cancer-associated fibroblast subtype heterogeneity in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2024;129(5):860-8

46. Akagawa S, Ohuchida K, Torata N, Hattori M, Eguchi D, Fujiwara K. et al. Peritoneal myofibroblasts at metastatic foci promote dissemination of pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol. 2014;45(1):113-20

47. Nagathihalli NS, Castellanos JA, Vansaun MN, Dai X, Ambrose M, Guo Q. et al. Pancreatic stellate cell secreted IL-6 stimulates STAT3 dependent invasiveness of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7(40):65982-92

48. Erkan M, Michalski CW, Rieder S, Reiser-Erkan C, Abiatari I, Kolb A. et al. The Activated Stroma Index Is a Novel and Independent Prognostic Marker in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;6(10):1155-61

49. Ogawa Y, Masugi Y, Abe T, Yamazaki K, Ueno A, Fujii-Nishimura Y. et al. Three distinct stroma types in human pancreatic cancer identified by image analysis of fibroblast subpopulations and collagen. Clinical Cancer Research. 2021;27(1):107-19

50. Belle JI, Sen D, Baer JM, Liu X, Lander VE, Ye J. et al. Senescence Defines a Distinct Subset of Myofibroblasts That Orchestrates Immunosuppression in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(7):1324-55

51. Mucciolo G, Araos Henríquez J, Jihad M, Pinto Teles S, Manansala JS, Li W. et al. EGFR-activated myofibroblasts promote metastasis of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(1):101-118.e11

52. Sangrador I, Molero X, Campbell F, Franch-Exposito S, Rovira-Rigau M, Samper E. et al. Zeb1 in stromal myofibroblasts promotes kras-driven development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(10):2624-37

53. Krebs AM, Mitschke J, Losada ML, Schmalhofer O, Boerries M, Busch H. et al. The EMT-activator Zeb1 is a key factor for cell plasticity and promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(5):518-29

54. Huang H, Daniluk J, Liu Y, Chu J, Li Z, Ji B. et al. Oncogenic K-Ras requires activation for enhanced activity. Oncogene. 2014;33(4):532-5

55. Yamasaki A, Yanai K, Onishi H. Hypoxia and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2020;484:9-15

56. Eguchi D, Ikenaga N, Ohuchida K, Kozono S, Cui L, Fujiwara K. et al. Hypoxia enhances the interaction between pancreatic stellate cells and cancer cells via increased secretion of connective tissue growth factor. Journal of Surgical Research. 2013;181(2):225-33

57. Müerköster SS, Werbing V, Koch D, Sipos B, Ammerpohl O, Kalthoff H. et al. Role of myofibroblasts in innate chemoresistance of pancreatic carcinoma - Epigenetic downregulation of caspases. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(8):1751-60

58. Schäfer H, Geismann C, Heneweer C, Egberts JH, Korniienko O, Kiefel H. et al. Myofibroblast-induced tumorigenicity of pancreatic ductal epithelial cells is L1CAM dependent. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(1):84-93

59. Sousa CM, Biancur DE, Wang X, Halbrook CJ, Sherman MH, Zhang L. et al. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature. 2016;536(7617):479-83

60. Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic Targeting of the Stroma Ablates Physical Barriers to Treatment of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):418-29

61. Chen Y, Kim J, Yang S, Wang H, Wu CJ, Sugimoto H. et al. Type I collagen deletion in αSMA+ myofibroblasts augments immune suppression and accelerates progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(4):548-565.e6

62. Duan Y, Zhang X, Ying H, Xu J, Yang H, Sun K. et al. Targeting MFAP5 in cancer-associated fibroblasts sensitizes pancreatic cancer to PD-L1-based immunochemotherapy via remodeling the matrix. Oncogene. 2023;42(25):2061-73

63. de Paula Carneiro Cysneiros MA, Cirqueira MB, de Figueiredo Barbosa L, de Oliveira ÊC, Morais LK, Wastowski IJ. et al. Immune cells and checkpoints in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Association with clinical and pathological characteristics. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0305648

64. Krishnamurty AT, Shyer JA, Thai M, Gandham V, Buechler MB, Yang YA. et al. LRRC15+ myofibroblasts dictate the stromal setpoint to suppress tumour immunity. Nature. 2022;611(7934):148-54

65. Hutton C, Heider F, Blanco-Gomez A, Banyard A, Kononov A, Zhang X. et al. Single-cell analysis defines a pancreatic fibroblast lineage that supports anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(9):1227-1244.e20

66. Patel MB, Pothula SP, Xu Z, Lee AK, Goldstein D, Pirola RC. et al. The role of the hepatocyte growth factor/c-MET pathway in pancreatic stellate cell-endothelial cell interactions: antiangiogenic implications in pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(8):1891-900

67. Erkan M, Reiser-Erkan C, Michalski CW, Deucker S, Sauliunaite D, Streit S. et al. Cancer-Stellate Cell Interactions Perpetuate the Hypoxia-Fibrosis Cycle in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2009;11(5):497

68. Nan L, Qin T, Xiao Y, Qian W, Li J, Wang Z. et al. Pancreatic Stellate Cells Facilitate Perineural Invasion of Pancreatic Cancer via HGF/c-Met Pathway. Cell Transplant. 2019;28(9-10):1289-98

69. Heger U, Martens A, Schillings L, Walter B, Hartmann D, Hinz U. et al. Myofibroblastic CAF Density, Not Activated Stroma Index, Indicates Prognosis after Neoadjuvant Therapy of Pancreatic Carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14(16):3881

70. Bhattacharjee S, Hamberger F, Ravichandra A, Miller M, Nair A, Affo S. et al. Tumor restriction by type I collagen opposes tumor-promoting effects of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2021;131(11):e146987

71. Wu Z, Wu Y, Wang M, Chen D, Lv J, Yan J. et al. FAP-activated liposomes achieved specific macropinocytosis uptake by pancreatic stellate cells for efficient desmoplasia reversal. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2024;495:153369

72. Van Cutsem E, Tempero MA, Sigal D, Oh DY, Fazio N, Macarulla T. et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Pegvorhyaluronidase Alfa with Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine for Patients with Hyaluronan-High Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(27):3185-94

73. Francescone R, Crawford HC, Barbosa Vendramini-Costa D. Rethinking the Roles of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;17(5):737-43

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Iwona Inkielewicz-Stepniak, Email: iwona.inkielewicz-stepniakedu.pl.

Corresponding author: Iwona Inkielewicz-Stepniak, Email: iwona.inkielewicz-stepniakedu.pl.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact