Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(4):2047-2064. doi:10.7150/ijbs.125245 This issue Cite

Research Paper

AMPKα1 Deficiency in Macrophages Impairs Tendon Regeneration and Tendon Stem Cell Function via TNF-α-FBP2 Signaling

1. Central Laboratory, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, Beijing 100081, China.

2. Department of Orthodontics, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, Beijing 100081, China.

3. National Center for Stomatology & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & National Engineering Laboratory for Digital and Material Technology of Stomatology & Beijing Key Laboratory of Digital Stomatology & Research Center of Engineering and Technology for Computerized Dentistry Ministry of Health & NMPA Key Laboratory for Dental Materials, Beijing 100081, China.

4. Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Tooth Restoration and Regeneration & Tongji Research Institute of Stomatology & Department of Orthodontics, Shanghai Tongji Stomatological Hospital and Dental School, Tongji University, Shanghai 200072, China.

5. Beijing Advanced Center of Cellular Homeostasis and Aging-Related Diseases, Institute of Advanced Clinical Medicine, Peking University, Beijing 100191, China.

†These authors contributed equally: Lisha Zhu, Yu Wang, Xinmeng Shi.

Received 2025-9-15; Accepted 2026-1-8; Published 2026-1-22

Abstract

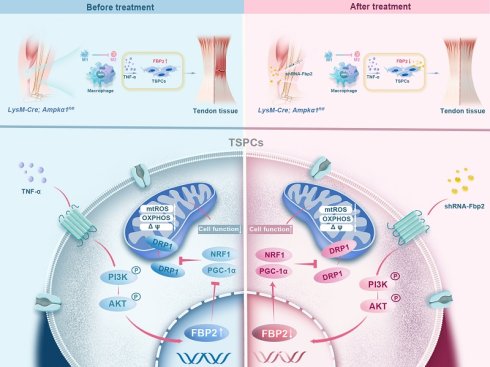

Tendon healing is limited by the minimal intrinsic regenerative capacity of the tissue, resulting in the formation of fibrovascular scar tissue rather than functional regeneration. Macrophage immunometabolism governs the balance between inflammation and repair; however, its effects on tendon regeneration are poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the differential activation of macrophage AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and its phenotypic alterations in neonatal and adult tendon injury models. Using myeloid-specific AMPKα1 knockout (LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl) mice, we found that macrophage AMPKα1 deficiency impairs tendon regeneration and repair capacity, leading to compromised proliferation, migration, and differentiation functions of tendon stem/progenitor cells (TSPCs). Mechanistically, AMPKα1-deficient macrophages exhibited increased TNF-α production, which promoted the expression of Fructose-bisphosphatase 2 (FBP2) in a PI3K/AKT-dependent manner. In addition, FBP2 can modulate mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics through a non-enzymatic mechanism and facilitate tissue repair and regeneration. Collectively, these findings underscore the immunometabolism mechanism linking macrophage AMPKα1 activity to stem cell injury responses via a TNF-α-FBP2 axis and provide new insights into the role of FBP2 for regulating stem cells.

Keywords: macrophage, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 2, tendon stem/progenitor cells, tendon regeneration

Introduction

Tendon injury is a challenging and prevalent motor system disease that compromises daily activities and leads to disability [1]. Failure of the injury repair process is often attributed to insufficient regenerative capacity and dysregulation of the immune microenvironment [1, 2]. Macrophages, as pivotal components of the innate immune system, play versatile roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis [3-5]. Initially, they exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype but subsequently repolarize toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype to actively support tendon regeneration [6, 7]. In recent years, several studies have investigated the influence of macrophage behavior on tendon regeneration [8, 9]. However, the molecular mechanisms governing macrophage function in the tendons remain largely unknown.

Effective tendon regeneration requires coordinated interactions between immune cells and tendon stem/progenitor cells (TSPCs). Macrophages secrete a range of immune cell mediators that regulate stem cell proliferation and govern stem cell-mediated tissue repair [10-12]. TSPCs play a crucial role in tendon repair and are characterized by their robust tenogenic and self-renewal potential [13]. They are highly enriched, maintained by their microenvironment (the 'niche'), and respond robustly to environmental stimuli [14]. However, the mechanism by which macrophages affect stem cell behavior remains unclear. Our previous work revealed that the regenerative capacity of tendons in the neonatal period was superior to that in adults [15], and emerging literature has demonstrated that macrophages of different ages have distinct effects on tissue repair [16, 17]. For example, neonatal macrophages exhibit weak inflammatory responses and effectively enhance cell proliferation [18]. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying this differential response pattern is critical for modulating macrophage function and could provide potential regulatory targets for tendon regeneration.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) regulates multiple metabolic processes that maintain cellular energy homeostasis [19]. Activation of this pathway is essential for metabolic and functional adaptations of macrophages [20]. Specifically, phosphorylation of AMPKα1 contributes to the switch in the macrophage phenotype from pro- to anti-inflammatory [21, 22]. However, whether macrophage AMPKα1 plays a functional role in tendon repair remains unknown. In this study, we demonstrated the functional disparity and differential activation of AMPKα1 in macrophages following tendon injury in both newborn and adult mice. Using a conditional genetic knockout mouse model, we investigated not only the influence of AMPKα1 deficiency in macrophages on tendon repair quality but also its mechanistic effects on TSPCs. Our results demonstrate that fructose-bisphosphatase 2 (FBP2), a multifunctional protein in the downstream TNF-α/AKT signaling [23, 24], impairs the function and regenerative capacity of TSPCs by compromising mitochondrial integrity and function. Overall, we identified a previously unknown role of macrophage AMPKα1 in regulating tendon tissue repair and revealed a key biological mechanism of TNF-α/AKT/FBP2 in response to mitochondria damage and tendon injury. These findings provide new insights into the enhancement of endogenous regenerative capacity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male C57 mice aged 0-1 day and 12 weeks and 6-8-week-old BALB/c nude mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (China). LysM-Cre mice were crossed with Ampkα1flox/flox mice to generate transgenic mice with specific deletion of macrophage Ampkα1 through backcrossing and subsequent progeny selection (LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice), along with littermate controls (Ampkα1fl/fl). Genomic DNA from the mouse tail was used for genotype identification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The DNA primers are listed in Table S1. All animals were housed in ventilated cages under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. During different experiments, mice were excluded if they died prematurely or suffered from tumors.

Tendon transection models

For tendon transection, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1% pentobarbital (0.1 mL per 100 g). After complete anesthesia, the Achilles tendon was exposed through lateral transection. A transverse incision of the Achilles tendon was made on each leg using microsurgical instruments. The wound was irrigated, and the skin was closed with sutures. Subsequently, the mice were euthanized at planned postoperative time points (1, 4, and 8 weeks) with an overdose of anesthesia, and the repair tissues were collected. Specifically, the wild-type mice (including neonatal and adult mice) were used to study the acute phase of inflammation and early regeneration, which typically peaks within 7 days. In contrast, the AMPKα1-deficient model was designed to assess long-term regeneration and tissue maturation, which require longer time points (4-8 weeks).

In vivo knockdown of Fbp2 by AAV9-shRNA

For tendon-specific knockdown of Fbp2 in mice, AAV9 vectors expressing shRNA targeting Fbp2 (AAV9-shRNA-Fbp2) or a non-targeting control shRNA (AAV9-shRNA-NC, Ctrl AAV) were constructed by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Neonatal mice received a local injection of 10 µL of AAV9-shRNA-Fbp2 or AAV9-shRNA-NC at a titer of 1 × 10¹² viral genomes (vg) /mL. Adult mice were administered 30 µL of the same viral preparation via local injection. Tendon tissues were harvested at 4 and 8 weeks post-injection. The targeting sequence for AAV9-shRNA-Fbp2 was 5'-CTGGATGGATCTTCAAACATT-3'; the control shRNA sequence was 5'-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3'.

Isolation and culture of TSPCs

Primary TSPCs were harvested from control (Ampkα1fl/fl) mice and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice according to the established procedure [25, 26]. The harvested tendons were minced and digested completely with 3 mg/mL collagenase type I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 4 mg/mL dispase (Roche) at 37°C for 1 h. After passing through a 70-μm strainer, single-cell suspensions were cultured in low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Hyclone) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. When the cells reached 80-90% confluence, they were passaged. TSPCs at passages 1-3 were used for subsequent experiments. A list of reagents and resources is provided in Table S2.

Isolation, culture, and polarization of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs)

BMDMs were isolated from control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice as previously described [25]. Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from the femurs, isolated using Lymphoprep (STEMCELL), and cultured for 5-7 days in RPMI 1640 medium (Solarbio) containing 10% FBS (Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 20 ng/mL recombinant mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, Peprotech). The culture medium was changed once every 3 days. After 5-7 days, the supernatant of macrophages from control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice were collected for further experiments. Macrophage polarization in vitro was performed as previously described [27].

TSPC differentiation in BMDM-conditioned medium

For the differentiation experiments, TSPCs were cultured in 12-well plates (50,000 cells/well). Tenogenic differentiation was induced using a corresponding differentiation medium supplemented with the supernatant collected from the BMDM-conditioned medium at a ratio of 1:1. The tenogenic differentiation medium contained growth medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Peprotech), 10 ng/mL GDF-5 (R&D System), and 0.05 mM l-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate. After 7 days of culture, quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to analyze the expression of tenogenic-related genes. Two weeks after tenogenic induction, the cells were assayed by Sirius Red staining (Solarbio, Beijing, China) to assess their tenogenic differentiation capacity.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown

siRNA sequences of the target gene markers were synthesized by GenePharma (China). Cells were diluted to a suitable density and seeded onto a plate. After 24 h at 70-80% confluence, the cells were treated with siRNA (50 nM) using the jetPRIME reagent (Polyplus, France) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table S3.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from primary cells and tendon tissues using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then, the mRNA was converted to complementary DNA by reverse transcription, and PCR was performed using gene-specific primers and SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a 7900HT Fast Time PCR system. The synthesized primers are listed in Table S4.

Western blotting

Total proteins from cell lysates and tissue homogenates were harvested using RIPA Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell lysate proteins were separated using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and blocked with 5% nonfat milk. The membranes were probed with corresponding primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed three times in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 for 5-10 min each, incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h, washed twice in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20, and imaged. Detailed information on the primary and secondary antibodies is provided in Table S5.

Staining of cells and tissue sections

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE), Sirius red, and Masson's trichrome staining were performed according to standard procedures to examine the general appearance of the soft tissues or cells. For immunofluorescence staining, sections (paraffin-embedded or frozen sections) or cells were incubated with anti-p-AMPK, anti-AMPK, anti-F4/80, anti-CD206, anti-NOS2, anti-CD86, anti-CD68, anti-Ki67, anti-SCX, anti-TNC, anti-TNMD, anti-FMOD, or anti-FBP2 antibodies. Next, sections or cells were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Confocal microscopic images were acquired using a laser-scanning microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss, Germany) and processed using LSM 5 Release 4.2 software.

Gene expression analysis

Differential gene expression was evaluated by transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq). tendon tissues from control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice (3 mice per condition, neonatal mice) were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analyses. Subsequently, cDNA library construction, library purification, and transcriptome sequencing were performed according to the instructions of the Wuhan Huada Sequencing Company (www.genomics.org.cn; BGI, Shenzhen, China).

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

To characterize the fiber morphology of the neo-tissues using field emission scanning electron microscopy, all glass slide samples underwent dewaxing, dehydration, and subsequent gold sputter coating at 20 mA for 100 s. Thereafter, the microstructures of the neo-tissues were observed, and images were captured using SEM (Hitachi SU8020, Japan) at 15 kV.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The ultra structures of the neo-tissues and cells were examined by TEM (Hitachi HT7700, Japan) at 100 kV. The samples were double-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (Sigma Aldrich), stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate, and embedded in epoxy resin. Transverse and longitudinal ultrathin sections (70-100 nm) were prepared using a Leica ultramicrotome and placed on copper grids. Counting and measurement of the collagen diameter and mitochondrial mass from TEM images were performed using ImageJ software.

Atomic force microscope (AFM)

The Young's modulus of tendon tissues was quantified using an atomic force microscope (AFM; Dimension Icon, Bruker, USA) in PeakForce Tapping mode. Scanning was performed at a rate of 1.0 Hz with an amplitude set point of 250 mV. A TAP150A probe was employed, and deflection sensitivity was calibrated against a sapphire reference sample. Data processing and analysis were conducted using Nanoscope Analysis software (version 1.60).

Mitochondrial morphology and mass

The mitochondrial morphology and mass of TSPCs were evaluated by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy using the fluorescent dye MitoTracker Red (Beyotime, China) and by TEM analysis. In addition, mtDNA was quantified using qPCR to measure the ratio of mtDNA to genomic DNA. The primer sequences are presented in Table S4.

Mitochondria electric potential (Δψ)

The mitochondrial membrane potential was monitored using JC1 staining (Solarbio, China). Briefly, cells were incubated with 10 μg/mL of JC-1 working solution for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. JC-1 monomer fluorescence (green) was detected at 525 nm (emission) and JC-1 polymer fluorescence (red) was detected at 590 nm (emission). The images were captured using a fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative data are presented as means ± SD. Unpaired t-tests were performed to assess whether statistical differences existed between the two groups. Multiple comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's post-hoc test, with p-values < 0.05 considered significant. The significance level is presented as *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 and **** p < 0.0001. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism® software (version 9.0, GraphPad Software Inc, California, USA).

Results

Activation of AMPKα1 in macrophages promotes neonatal tendon healing

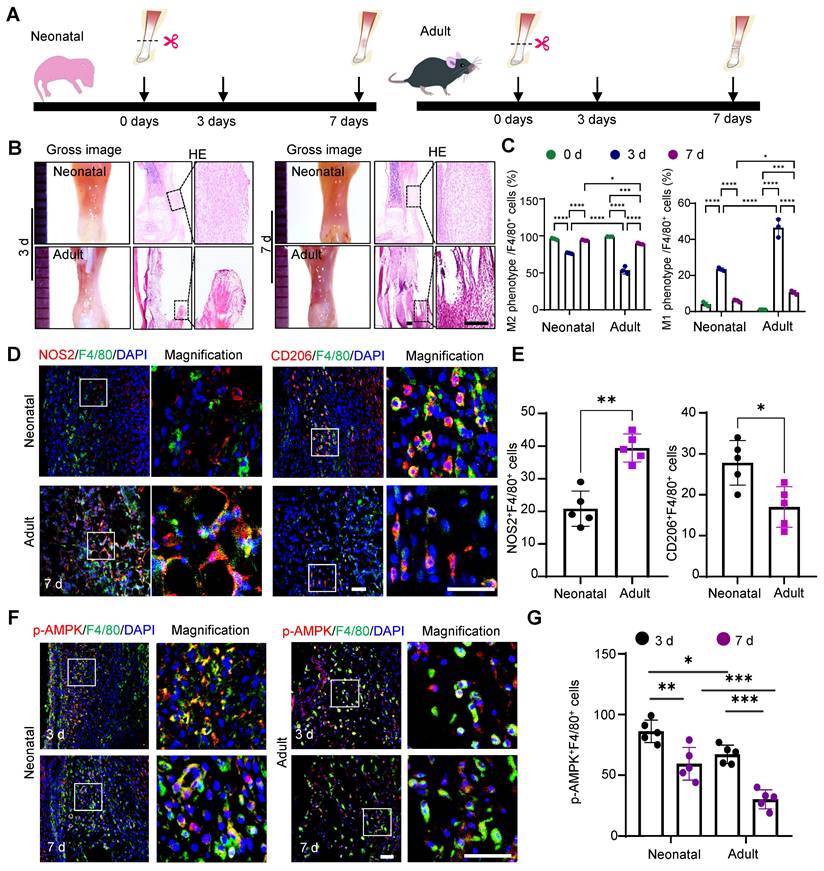

To investigate the differential macrophage responses to tendon injury between the neonatal and adult stages, we established a tendon transection model in neonatal (0-1 days) and adult (12 weeks) mice (Fig. 1A) [28]. Seven days after injury, the neonatal tendon tissue exhibited superior healing compared to the adult group, characterized by a relatively orderly collagen fiber arrangement and a significant decrease in inflammatory cells compared to that on day 3. In contrast, adult tendon tissue displayed marked collagen fiber disruption, prominent adhesion at the ends, and evident inflammatory infiltration (Fig. 1B). The switch from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype is essential for the transition from an initial injury response to the tissue repair phase. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that neonatal mice exhibited earlier activation of the anti-inflammatory cluster of M2 macrophages (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206+) and more rapid recession of pro-inflammatory M1 (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206-) macrophages (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). Immunofluorescence staining also confirmed that 7 days after injury, the percentage of anti-inflammatory macrophages (~29% CD206+F4/80+) in the tendon tissues of neonatal mice was significantly higher than that in adult mice (~18% CD206+F4/80+). Conversely, the neonatal group had significantly fewer pro-inflammatory macrophages (~19% NOS2+F4/80+) than the adult group (~39% NOS2+F4/80+) (Fig. 1D, E).

Differential activation of macrophage AMPKα1 during neonatal and adult tendon injury processes. (A) Schematic image of the transected tendon model in newborn and adult mice. (B) Gross view and HE staining of tendon in newborn and adult mice at 3 and 7 days after injury. Scale bars: 200 µm. (C) Quantitative flow cytometry results of M1 (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206-) and M2 (CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206+) in the tendon tissue of newborn and adult mice at 0, 3 and 7 days after injury (n = 3). (D) Immunofluorescent co-staining of NOS2 or CD206 (red) with F4/80 (green) in tendon derived from newborn and adult mice at 7 days after injury. Scale bars: 50 µm. (E) Left: number of NOS2 and F4/80 double-positive cells among F4/80-positive cells. Right: number of CD206 and F4/80 double-positive cells among F4/80-positive cells at 7 days (n = 5). (F) Immunofluorescent co-staining of p-AMPK (red) with F4/80 (green) in tendon derived from newborn and adult mice at 3 and 7 days after injury. Scale bars: 50 µm. (G) Number of p-AMPK and F4/80 double-positive cells among F4/80-positive cells at 3 and 7 days after injury (n = 5). * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001.

AMPKα1 serves as a critical regulator of macrophage metabolism, function, and polarization [29]. Therefore, we examined the AMPKα1 expression in macrophages at 3- and 7-days post-injury. The results revealed significant AMPK activation in macrophages, with a higher number of phosphorylated AMP-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK)-positive cells in neonatal mice than in adult mice (Fig. 1F, G). Taken together, the in vivo findings highlight the variations in healing outcomes and macrophage phenotypes between neonatal and adult mice, implying that the differential activation of AMPK in macrophages during tendon injury may play a role in regulating macrophage phenotypes and orchestrating tendon regeneration.

AMPKα1 deficiency impedes the transition of macrophage to an anti-inflammatory phenotype

Next, to determine whether AMPKα1 deficiency affects macrophage functionality, we generated the myeloid-specific Ampkα1 knockout mice (LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl) and used their littermate Ampkfl/fl mice as controls. First, the genotyping PCR and western blotting results verified the knockout efficiency at both the genomic and protein levels (Fig. S2A, B). The relationship between AMPKα1 activation and macrophage function was also investigated in vitro. Primary BMDMs obtained from Ampkfl/fl and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice. Furthermore, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interleukin 4 (IL-4) were used to induce the polarization of BMDMs toward M1 pro-inflammatory and M2 inflammatory-resolving phenotypes, respectively. BMDMs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice exhibited increased expression of the M1 macrophage markers NOS2 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and decreased expression of the M2 macrophage markers YM1 and CD206 at both the gene and protein levels (Fig. S3A-D). Furthermore, we observed significant differences in cytokine secretion by macrophages between Ampkα1fl/fl and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice. Specifically, the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 were significantly reduced, whereas the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α were markedly elevated (Fig. S3E). Efferocytosis is another crucial function of macrophages in maintaining homeostasis by clearing apoptotic cells [30]. Here, we observed that the capacity of phagocytosis was significantly reduced in AMPKα1-deficient macrophages. Specifically, BMDMs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice showed a lower phagocytic index (~42%) than BMDMs from Ampkfl/fl (~19%) mice (Fig. S3F). These results suggested that the absence of AMPKα1 in macrophages impedes their transition to an anti-inflammatory phenotype and significantly diminishes their phagocytic activity.

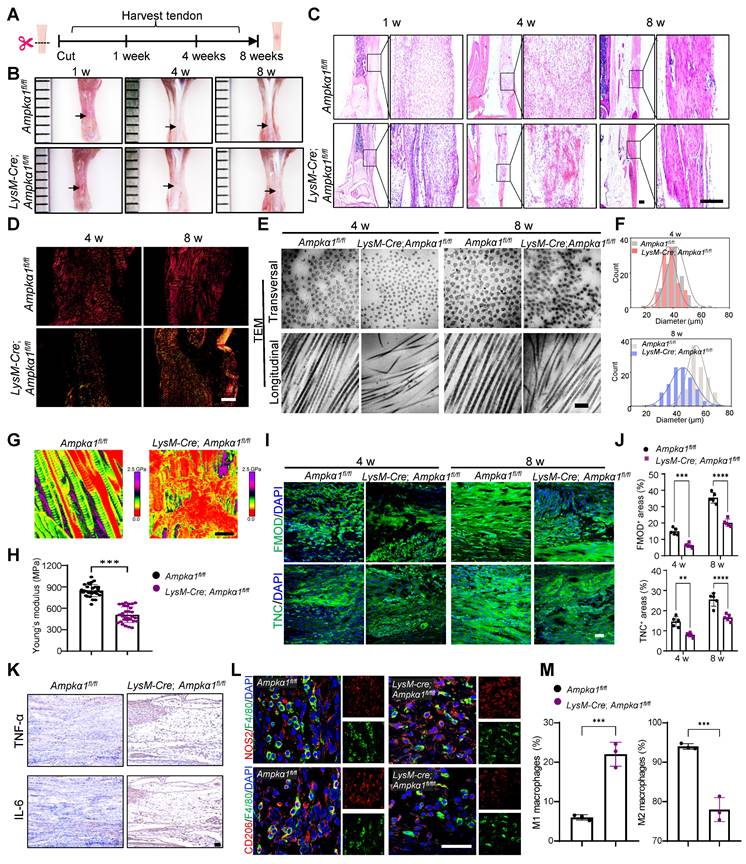

Macrophage AMPKα1 deficiency impairs tendon repair and regeneration

To further investigate the influence of macrophage AMPKα1 loss on neonatal tendon regeneration, tendon transection models in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl neonatal mice were established, and samples were harvested at 1-, 4-, and 8-weeks post-injury, respectively (Fig. 2A). The results revealed that, compared to the control group, the tendon repair area in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group exhibited poorer smoothness and flatness, with translucent collagen tissue deposition and reduction in overall tendon length at 4- and 8-weeks post-operation (Fig. 2B and Fig. S4A). At 1-week post-injury, disorganized and scattered fiber were observed in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group. Similarly, compared to the control group, the regenerated tendon collagen fibers in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice appeared looser, more disorganized, and less mature at 4 and 8 weeks post-injury (Fig. 2C, D). To further compare the collagen fibril distribution and diameter at the nanoscale level, specimens were observed under TEM and SEM (Fig. 2E, F and Fig. S4B). Representative images revealed increased collagen fibril entanglement and disorganization in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group at 4- and 8-weeks post-operation. To assess the relationship between fibril pattern and tendon mechanics, AFM was performed to examine the fibrillar crimp and Young's modulus of the regenerated tendons (Fig. 2G, H). The average Young's modulus was ~508 MPa in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group, compared to ~847 MPa in the control group. These findings indicate that Ampkα1 expression in macrophages is both necessary and sufficient for the regeneration of tendons with competent tensile mechanical properties.

During tendon injury, multiple tendon-resident cells coordinate with macrophages in the inflamed tissue to achieve efficient repair [31]. Scleraxis-lineage (ScxLin) cells are vital during the process of neonatal tendon repair [32] and may include tendon progenitor cells and differentiated tenocytes. Compared to the control group, a significant decrease in the percentage of Ki67+SCX+ cells and AMPK+F4/80+ macrophages were observed in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group at 1 and 4 weeks post-injury (Fig. S4C, D). This preliminary finding suggested an impaired proliferation capacity of tendon cells in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice, potentially resulting from macrophage AMPKα1 deficiency. Additionally, histological analysis at 4- and 8-weeks post-injury revealed markedly reduced expression of tendon-related factors fibromodulin (FMOD) and tenascin-C (TNC), along with more disordered nuclear arrangement in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group compared to the control group (Fig. 2I, J), suggesting impaired regenerative and differentiation capacity of tendon cells. Given that AMPKα1 phosphorylation may favor anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization, we further examined the inflammatory profile by analyzing canonical M1/M2 macrophage markers and pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-αand anti-inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 (Fig. 2K-M and Fig. S4E, F). Compared with the control group, the number of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages cells and the level of pro-inflammatory factors IL-6 and TNFα increased significantly in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice, while the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β and IL-10) was significantly reduced. Together, these findings imply that loss of Ampkα1 in macrophages disrupts the inflammatory microenvironment, impairs tendon cell function, and consequently compromises tendon regenerative capacity.

Macrophage AMPKα1 deficiency impairs tendon regeneration and repair capacity. (A) Scheme depicting of construction of the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice and littermate control mice (Ampkα1fl/fl), along with a schematic image of the transected tendon model. (B) Gross view of tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and control mice at 1-, 4- and 8-week after injury. Black arrows point to areas of tendon tissue damage. (C) Representative HE staining of the tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and control mice at 1-, 4- and 8-week postoperatively. Scale bars: 200 µm. (D) Representative Sirius red staining images of tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and control mice at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively, imaged using a polarized light microscope. Type I fibers (thick fibers, yellow-orange); Type III fibers (thin fibers, green). Scale bars: 100 µm. (E) Representative transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images illustrating the microstructural characteristic of regenerated collagen fibers in the control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group at 4 and 8 weeks after injury. Scale bars: 200 nm. (F) Frequency distribution profiles of fibril diameter in the tendon of control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group at 4 and 8 weeks after injury. (G) Representative atomic force microscope images of the tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and control mice at 8-week postoperatively. Scale bars: 400 nm. (H) Young's modulus of the tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and control mice. (I) Immunofluorescent staining of TNC and FMOD in tendon derived from control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice at 4 and 8 weeks after injury. Scale bars: 50 µm. (J) Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence staining of FMOD and TNC (n = 5). (K) Immunohistochemical staining of IL-6 and TNF-α in tendon derived from control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice at 1 week after injury. Scale bars: 200 µm. (L) Immunofluorescent detection of F4/80 and CD206 in tendon derived from control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice at 1 week after injury. Scale bars: 50 µm. (M) Flow cytometry analysis of the percentage of CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206+ macrophages and CD45+CD11b+F4/80+CD206- macrophages in the tendon of control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice at 1 week after injury (n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Ampkα1 deletion in macrophages impairs TSPC function

TSPCs are a vital population of tendon-resident cells. During tendon regeneration and repair, macrophages interact with TSPCs to modulate their proliferation, differentiation, and migration, which are crucial for effective tendon regeneration [33]. To understand how AMPKα1 deficiency in macrophages delays tendon repair, we first explored the potential functional alteration of TSPCs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice. We collected conditioned media from BMDMs of Ampkα1fl/fl and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice and used them to treat TSPCs (Fig. S5A). Immunofluorescence staining results showed that the TPSCs that were stimulated by the conditioned medium from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl BMDMs displayed lower proliferation capacity (Fig. S5B, C). Correspondingly, there was a notable decrease in the colony-forming capacity of TSPCs in vitro following stimulation with conditioned medium from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl BMDMs (Fig. S5D, E). Subsequently, we assessed the effects of conditioned media from both macrophage groups on TSPC migration using a scratch assay. The results demonstrated that the migration rate of TSPCs was reduced when treated with conditioned medium from the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group compared to that from the control group (Fig. S5F, G).

Furthermore, we induced tenogenic differentiation of TSPCs and supplemented the differentiation medium with conditioned medium from macrophages. The RT-qPCR results showed that TSPCs stimulated by the conditioned medium from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl BMDMs displayed a significant decrease in the mRNA expression of the tendon-related genes collagen I (Col1), Tnmd, and Tnc (Fig. S5H). Additionally, the Sirius Red staining results demonstrated that TSPCs stimulated with conditioned medium from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl BMDMs, also exhibited lower collagen matrix secretion (Fig. S5I, J). These in vitro findings further confirmed that the activation of AMPKα1 in macrophages can disturb the harmonious communication between the TSPCs and macrophages, which impairs multiple biological functions of TPSCs and contributes to the decreased tendon regenerative capacity in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice.

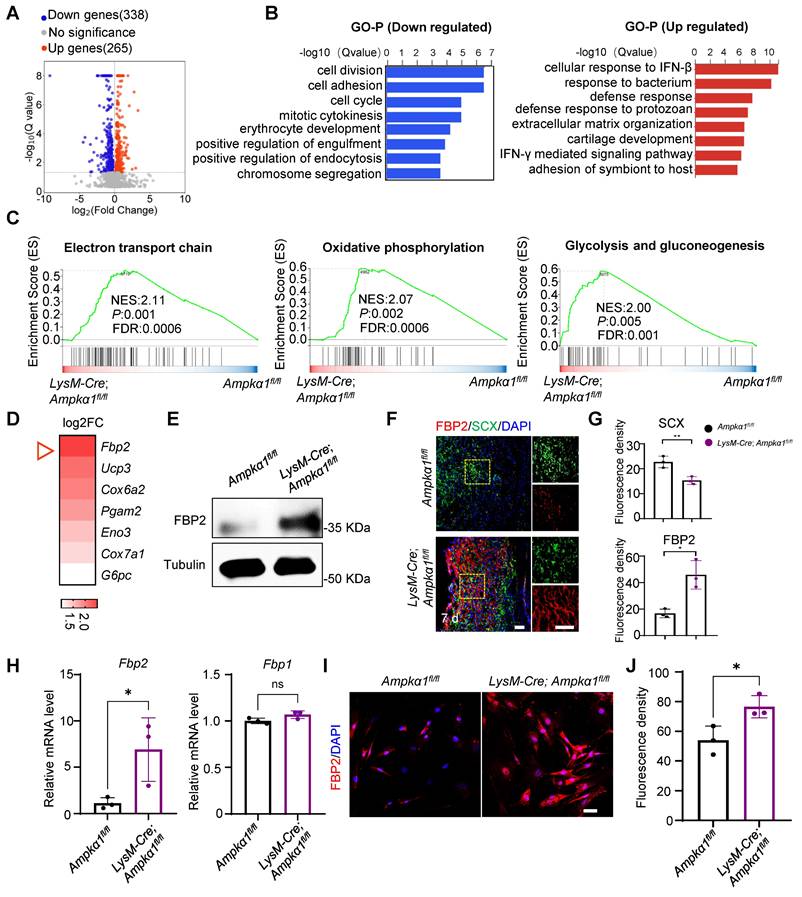

Ampkα1-deficient macrophages promote FBP2 upregulation in TSPCs

To gain further insights into the underlying mechanism of macrophage AMPKα1 in tendon regeneration, we performed RNA sequencing on tissues from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice and Ampkα1fl/fl mice 7 days after injury. Initial transcriptome analysis revealed a total of 603 differentially expressed genes between the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group and Ampkα1fl/fl group. Among these, 338 genes were downregulated, and 265 genes were upregulated (Fig. 3A). Subsequent Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of the upregulated and downregulated genes revealed significant enrichment of differentially expressed genes in categories such as cell division, cell proliferation, and cellular immune response (Fig. 3B). Additionally, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) pinpointed the “electron transport chain,” “oxidative phosphorylation,” and “glycolysis and gluconeogenesis” as key pathways involved in the upregulation of genes in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group post-injury (Fig. 3C). We further investigated the genes with significant differential expression (log2FC >1) in these three pathways. Notably, Fbp2 ranked first in the differential expression of upregulated genes in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group (Fig. 3D).

A previous study indicated that FBP2 is a key enzyme that limits gluconeogenesis, antagonizes glycolysis, and reduces glucose uptake [23]. Validation through western blotting and immunofluorescence staining confirmed that a consistent upregulation of FBP2 protein expression within tendon tissues of the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group (Fig. 3E, F). Meanwhile, we observed the co-localization of FBP2 and tendon-specific markers (SCX, CD146, and CD90) in damaged tissues, which are markers of TSPCs (Fig. 3F, G and Fig. S6). The results revealed that, compared to the Ampkα1fl/fl group, FBP2 expression was significantly upregulated in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group after tendon injury. To further investigate FBP2 expression specifically in TSPCs, we isolated cells from injured tendon tissues in both groups. We confirmed that Fbp2 was upregulated in the TSPCs of the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group at the mRNA level compared to controls, while no obvious change at the gene level was detected in Fbp1, an isozyme of FBP2 (Fig. 3H). Consistently, immunofluorescence staining certified markedly higher FBP2 protein levels in TSPCs from the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group than in controls (Fig. 3I, J).

The enhanced expression of FBP2 in tendon tissue of LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice after injury. (A) Volcano plots visualizing the gene expression for up/down-regulated genes in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl tendon tissue relative to control tissue after injury (n = 3). (B) Gene Ontology Biological Process (GO-BP) analysis of down- (left) and upregulated (right) genes (Top 10 biological pathways). (C) GSEA enrichment curves (based on WikiPathways database) depicting the three most significant enriched upregulated pathways. (D) The heatmap displaying genes ranked by log2FC values in (C). (E) Western blotting analysis of FBP2 expression in the tendon tissue of control and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice after injury. (F) Location of FBP2 in the TSPCs by immunofluorescence staining. (G) Quantification of FBP2 and SCX fluorescent intensity (n = 3). (H)The expression of Fbp2, and Fbp1 in TSPCs was evaluated by RT-PCR analysis (n = 3). (I) Immunofluorescence staining results showed the protein expression levels of FBP2 (red) in TSPCs derived from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group, compared to the control TSPCs. Scale bars: 20 µm. (J) Quantification of FBP2 fluorescent intensity (n = 3). ns: no significance; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

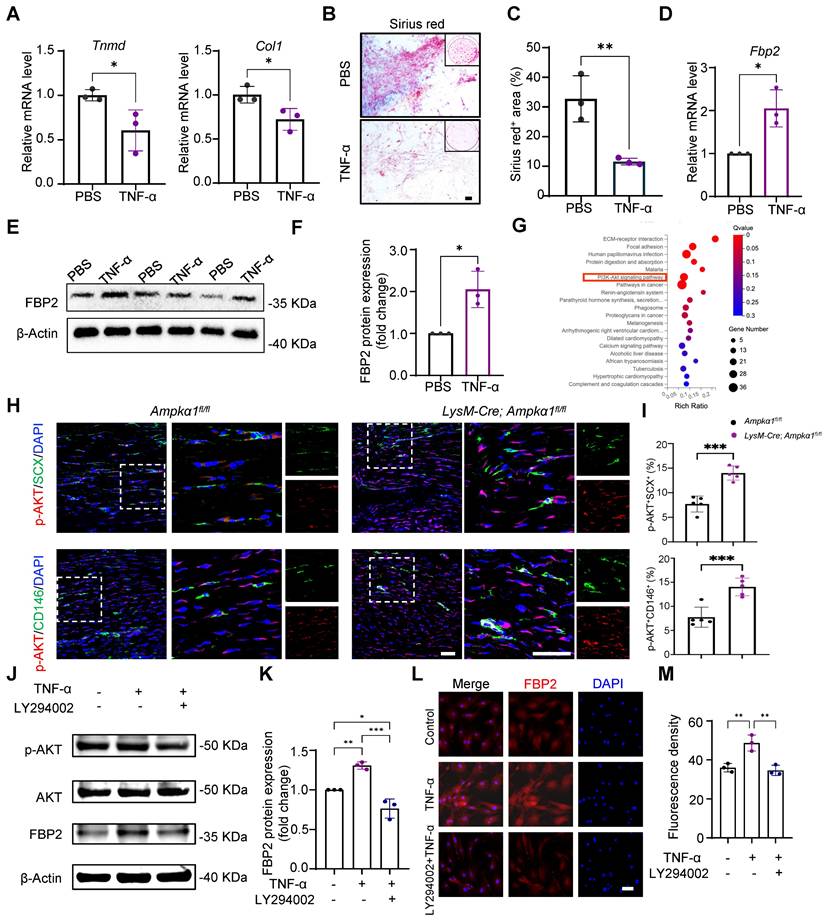

Elevated TNF-α in tendon niche increased FBP2 levels in a PI3K/AKT-dependent manner

Macrophages primarily modulate tissue repair through paracrine cytokines. Consistent with this, the above results showed that tendon and BMDMs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice displayed the persistently elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 (Fig. 2K and Fig. S4E, F). Notably, our previous study demonstrated that TNF-α stimulation impairs the differentiation capacity of TSPCs [28]. Build on this observation, we next investigated whether TNF-α drives the TSPC dysfunction seen in AMPKα1-deficient mice and simultaneously probed the downstream signaling mechanisms underlying this effect. Upon TNF-α treatment, mRNA expression of tendon marker genes Tnmd and Col1 significantly decreased (Fig. 4A). Sirius Red staining also showed that TNF-a stimulation reduced the collagen matrix secretion (Fig. 4B, C).

Simultaneously, we found that exposure to TNF-α markedly increased FBP2 expression in TSPCs relative to untreated controls (Fig. 4D-F). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis further showed that genes upregulated in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl tendons were significantly enriched in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Fig. 4G). Meanwhile, immunofluorescent staining results confirmed that compared to the Ampkα1fl/fl group, AKT activation of TSPCs was significantly increased in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group after tendon injury (Fig. 4H, I). It has been shown that TNF-α can drive metabolic reprogramming by promoting signaling through PI3K/AKT, which deteriorates the stem-cell state and cellular differentiation [34, 35]. To explore whether TNF-α affects FBP2 expression through the PI3K/AKT pathway, we applied the PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitor LY294002. The results revealed that PI3K/AKT was significantly inhibited by LY294002, and the expression of FBP2 was simultaneously inhibited (Fig. 4J-M). To directly validate the essential role of TNF-α in the proposed signaling axis, we have now performed additional rescue experiments using a TNF-α neutralizing antibody. Specifically, conditioned medium from AMPKα1-deficient macrophages was treated with an anti-TNF-α antibody prior to incubation with TSPCs. The results demonstrate that neutralization of TNF-α markedly attenuates the upregulation of FBP2 induced by AMPKα1-deficient macrophage-conditioned medium (Fig. S7A-D). Taken together, these findings indicate that AMPKα1 deletion in macrophages during tendon repair leads to high TNF-α expression, whereas the resulting high TNF-α levels within the tendon niche further cause AKT activation and FBP2 overexpression, deteriorating the tendon stem cell state.

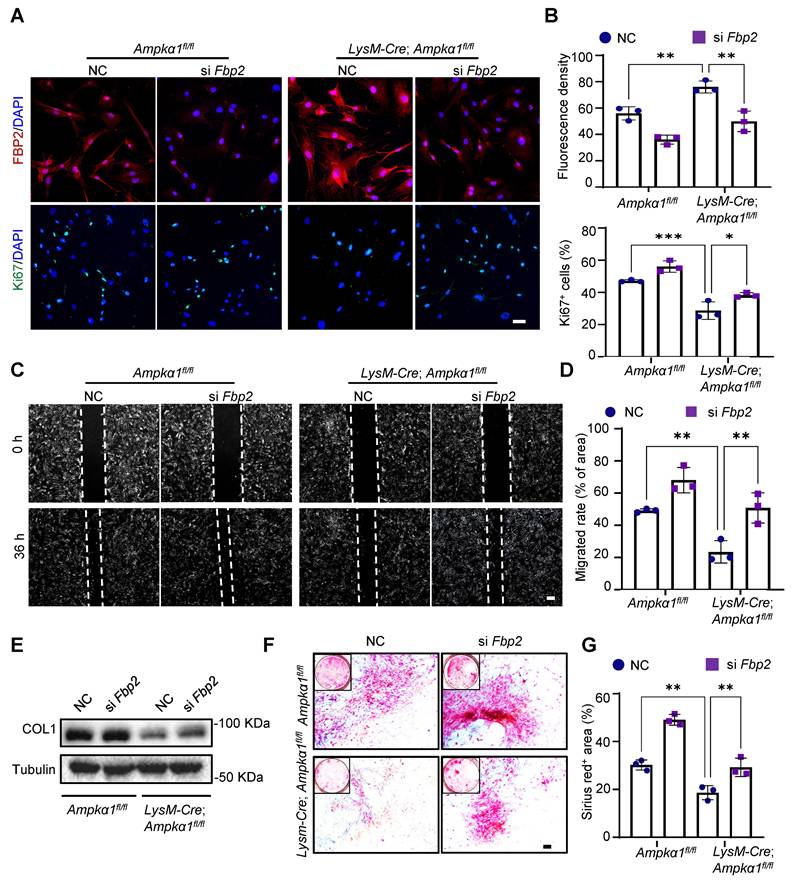

Knockdown of Fbp2 enhances TSPC function in vitro

We explored the regulatory role of FBP2 in proliferation, migration, and differentiation. We utilized small interfering RNA (siRNA) to silence the expression of Fbp2 in TSPCs (si Fbp2). siRNA (NC) was used as a control. Preliminary experiments confirmed that siRNA treatment significantly reduced FBP2 levels (Fig. S8A, B). Then, immunofluorescence staining results demonstrated that Fbp2 knockdown significantly increased the proportion of Ki67+ cell proportions in both LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl TSPCs and Ampkα1fl/fl group, thereby enhancing cell proliferation capacity (Fig. 5A, B). Moreover, wound healing experiments indicated that the knockdown of Fbp2 accelerated TSPC growth after scratching (Fig. 5C, D). Subsequently, the tenogenic differentiation capacity of TSPCs after knockdown was assessed. Western blotting results revealed that there was a remarkable declination in COL1 protein expression in TSPCs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice, which was reversed by the Fbp2 knockdown (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, Sirius Red staining results demonstrated that the Fbp2 knockdown remarkably restore the impaired tenogenic differentiation capacity of TSPCs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice, as evidenced by a significant increase in the proportion of positively stained areas in cells transfected with si Fbp2 (Fig. 5F, G). Collectively, these findings suggest that the knockdown of Fbp2 enhances the proliferation, migration, and tendon differentiation of TSPCs.

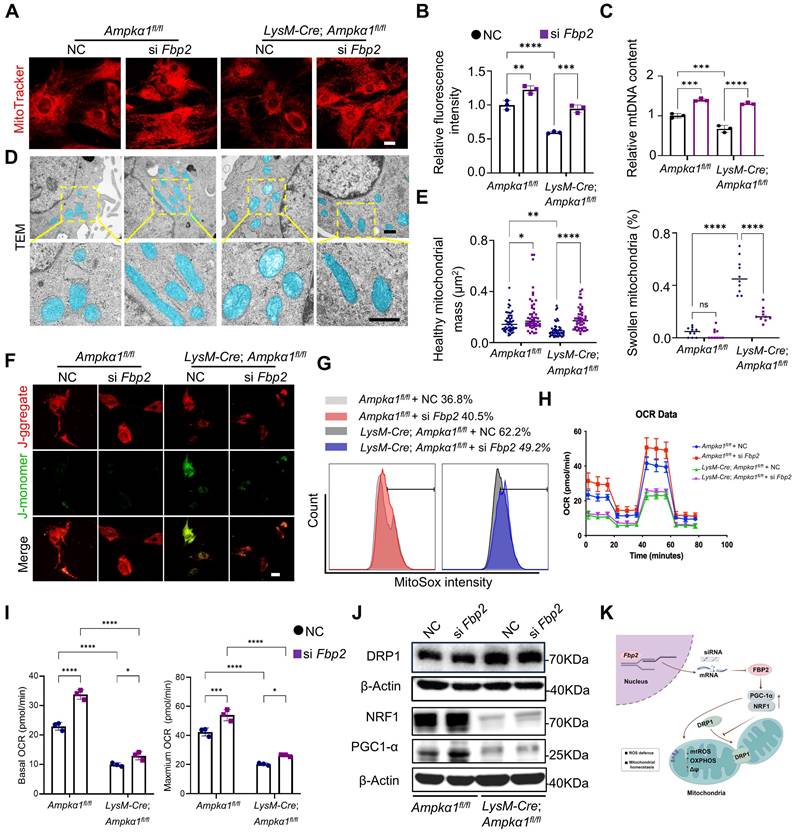

FBP2 leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and suppression of mitochondrial biogenesis

To address whether the effects of FBP2 on TSPCs are mediated by its enzymatic activity and downstream metabolites, we first focused on its canonical catalytic function. Specifically, we measured the levels of fructose-6-phosphate (F-6-P), the direct metabolic product of FBP2, and confirmed that FBP2 overexpression significantly increased intracellular F-6-P levels (Fig. S9A). To further determine whether this metabolite mediates the biological effects of FBP2, we examined the effects of exogenous F-6-P on TSPC proliferation and differentiation. However, exogenous supplementation of F-6-P to TSPCs did not significantly affect their proliferation or differentiation capacity, indicating that FBP2 may exert its effects through a non-enzymatic mechanism (Fig. S9 B-D). Indeed, emerging evidence suggests that FBP2 can regulate mitochondrial function via protein-protein interactions independent of its catalytic activity [36]. To elucidate the specific mechanism by which FBP2 regulates TSPC function, we compared the mitochondrial biogenesis and function of TSPCs in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and Ampkα1fl/fl group and investigated the impact of Fbp2 knockdown on TSPC mitochondria. Mitochondrial visualization of TSPCs and mitochondrial DNA content assays were performed.

TNF-α increased FBP2 levels through PI3K /AKT signaling. (A) The expression of Tnmd, and Col1 in TSPCs stimulated by TNF-α was evaluated by RT-PCR analysis (n = 3). (B) Photomicrographs of Sirius red staining of TSPCs stimulated by TNF-α for 10 days after tenogenic differentiation induction. Scale bars: 200 µm. (C) Quantification of Sirius red-positive areas (n = 3). (D) The expression of Fbp2 in TSPCs stimulated by TNF-α was evaluated by RT-PCR analysis (n = 3). (E) Western blotting analysis of FBP2 expression in TSPCs stimulated by TNF-α. (F) Quantification of western blotting results in (E). (G) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis of upregulated genes of LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group compared with control group. (H) Immunofluorescence staining results showed the protein expression levels of p-AKT (red) in TSPCs (green) of LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group and control group. Scale bars: 50 µm. (I) Quantification analysis of p-AKT+SCX+-positive cells and p-AKT+CD146+-positive cells (n = 5). (J) Western blotting analysis of p-AKT, AKT and FBP2 expression in TSPCs stimulated by TNF-α and/or LY294002. (K) Quantification of western blotting results in (J) (n = 3). (L) Immunofluorescence staining results showed the protein expression levels of FBP2 (red) in TSPCs stimulated by TNF-α and/or LY294002. Scale bars:50 µm. (M) Quantification of FBP2 fluorescent intensity (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Knockdown of Fbp2 promotes proliferation, migration, and differentiation capacity of TSPCs in vitro. (A) Immunofluorescence staining results showed the protein expression levels of FBP2 (red) and Ki67 (green) in Fbp2-knockdown TSPCs, compared to NC group. Scale bars: 20 µm. (B) Quantification of ratio of Ki67 positive cells and FBP2 fluorescent intensity (n = 3). (C) Representative images of the wound-healing assay of the TSPCs transfected with si Fbp2 at 0 h and 36 h post-scratch. Scale bars: 200 µm. (D) The percentage of recovered area in scratch assay (n = 3). (E) Western blotting analysis of COL1 expression in TSPCs transfected with si Fbp2. (F) Photomicrographs of Sirius red staining of TSPCs transfected with si Fbp2 were cultured for 10 days after tenogenic differentiation induction, the collagen fibers were stained red. Scale bars: 200 µm. (G) Quantification of Sirius red-positive areas (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The outcomes revealed that, compared to TSPCs of Ampkα1fl/fl mice, mitochondrial to nuclear DNA ratios were dramatically decreased in those of LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice (Fig. 6A-C). Simultaneously, Fbp2 knockdown in TSPCs of Ampkα1fl/fl mice facilitated mitochondrial DNA and enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis. Furthermore, TEM images showed that most TSPC mitochondria in the Ampkα1fl/fl group exhibited integrated structures, whereas those in the LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group, with elevated FBP2 expression, showed signs of swollen and fragmented mitochondria. In contrast, Fbp2 knockdown ameliorated the mitochondrial morphological phenotype and maintained mitochondrial health and quality (Fig. 6D, E). We surmised that the observed variations in mitochondrial mass and function between the different TSPC groups could be attributed to the inflammation-related high reactive oxygen species (ROS) microenvironment, and these changes were significantly attenuated by Fbp2 knockdown, indicating its protective role against oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial damage.

Downregulation of FBP2 promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and functions. (A) TSPCs transfected with si NC and si Fbp2 were stained with MitoTraker Red. Scale bars: 50 µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of fluorescence staining of MitoTracker (n = 3). (C) mtDNA content was determined by quantitative PCR (n = 3). mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA. (D) Pseudo-colored serial TEM images of TSPCs transfected with si NC and si Fbp2. Blue: mitochondria. Below: magnified view of yellow frame. Scale bars: 500 nm. (E) Quantitative analysis of mitochondria. Left: the number of healthy mitochondria. Right: the percentage of swollen mitochondria. (F) Representative JC1 fluorescence images of TSPCs transfected with si NC and si Fbp2. Red: JC1 dye in aggregated forms. Green: JC1 dye in monomeric forms. Scale bars: 50 µm. (G) TSPCs were labeled with MitoSOX Red, and MitoSOX Red fluorescence was analyzed using flow cytometry. (H) The levels of mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in TSPCs with different treatment (n = 3). (I) Quantitative data of OCR (n = 3). (J) Western blotting analysis of DRP1, NRF1, and PGC-1α expression in TSPCs transfected with si NC and si Fbp2. (K) Schematic illustration of the mechanism of action of FBP2 at the mitochondria in TSPCs. This figure was created using Figdraw. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

It was found that TSPCs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice exhibited the higher level of cellular and mitochondrial ROS compared with TSPCs from wild-type (WT) mice and displayed decreased mitochondrial membrane potential. Conversely, Fbp2 knockdown restored mitochondrial function, as indicated by normalization of the mitochondrial membrane potential and reduced excessive ROS production (Fig. 6F, G and Fig. S10A-D). To further evaluate mitochondrial function, the basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using a Seahorse analyzer. We found that the OCR of TSPCs from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice were reduced, and knockdown of Fbp2 significantly elevated the OCR over the control (Fig. 6H, I). To elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which FBP2 regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and function, we examined the expression of mitochondria-related regulators including peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α), nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) and dynamin-related protein-1 (DRP1). Our findings identified that DRP1-activated mitochondrial damage and fragmentation were alleviated by knockdown of Fbp2 (Fig. 6J and Fig. S10E). During this process, the knockdown of Fbp2 also protects against mitochondrial oxidative by activating the PGC-1α/NRF-1 pathway, thereby restoring mitochondrial homeostasis and promoting mitochondrial biogenesis. Overall, these results indicate that FBP2 is a significant contributor to mitochondrial ROS production and subsequent mitochondrial impairment, which in turn adversely affects stem cell function (Fig. 6K).

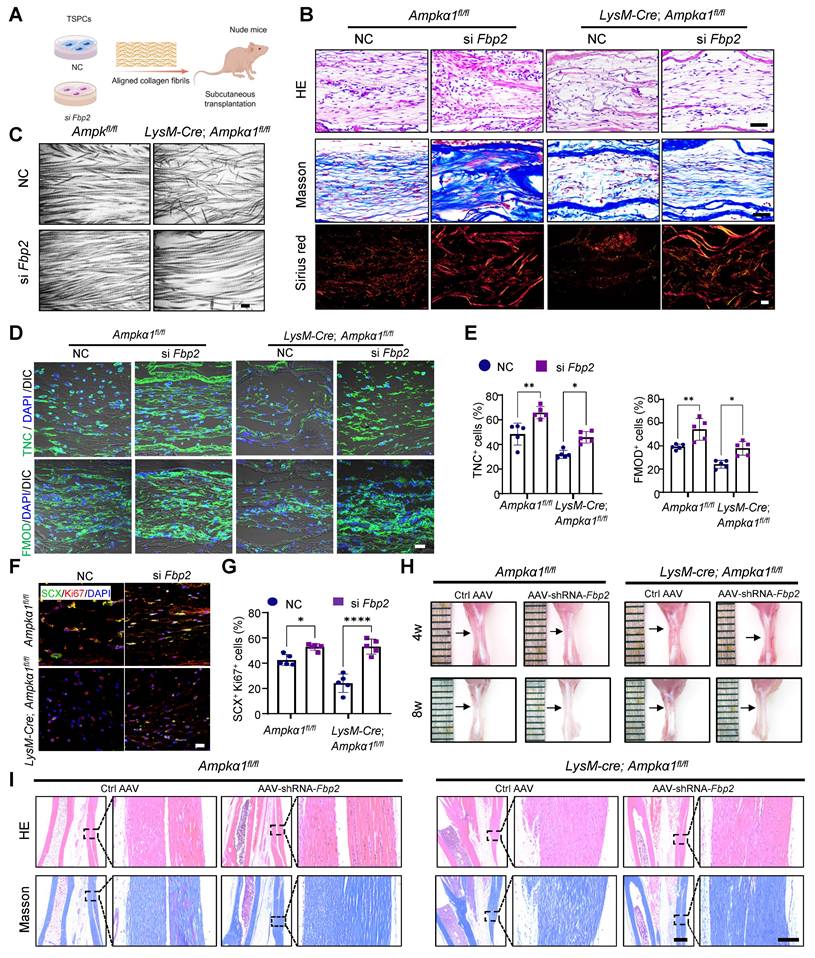

Fbp2 knockdown in TSPCs notably enhances tendon regeneration

To assess the effect of FBP2 on TSPC proliferation and tenogenic capacity in vivo, we used a biomimetic parallel collagen scaffold and loaded TSPCs with Fbp2 knockdown [26]. These cells were subcutaneously implanted into nude mice for in vivo functional validation (Fig. 7A). The grafts were harvested 8 weeks after implantation. HE staining and Masson's trichrome staining revealed that, in both the Ampkα1fl/fl group and LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group TSPCs with Fbp2 knockdown, the regenerated tendon tissue exhibited notably thicker and denser collagen fibers and deposited more collagen matrix than those in the NC group (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, TEM examination and Sirius Red staining confirmed that knocking down cellular Fbp2 facilitated the formation of orderly arranged collagen fibers and deposited collagen type I with higher maturity (Fig. 7B, C). Moreover, the si Fbp2 TSPCs showed a relatively higher proportion of TNC+ cells (~66% in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group; ~45% in Ampkα1fl/fl group) than the NC group (~48% in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group; ~32% in Ampkα1fl/fl group), the si Fbp2 TSPCs showed a relatively higher proportion of FMOD+ cells (~54% in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group; ~38% in Ampkα1fl/fl group) than the NC group (~39% in LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl group; ~24% in Ampkα1fl/fl group). These results also implied that the knockdown of Fbp2 could improve the tenogenic differentiation of TSPCs in vivo (Fig. 7D, E). Additionally, a greater percentage of SCX+Ki67+cells was observed in the regenerated tendon tissue of this group (Fig. 7F, G), which also confirmed that TSPCs after knocking down Fbp2 have superior in vivo tenogenesis capacity.

Next, to further validate the role of FBP2 in tendon regeneration, an AAV vector carrying Fbp2-shRNA was injected into the tendon tissue of LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice and Ampkα1fl/fl mice after injury, while an AAV carrying an empty vector served as the control. RT-qPCR results suggested that Fbp2-shRNA decreased cellular Fbp2 expression notably (Fig. S11A). Furthermore, gross observations revealed that both LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice and Ampkα1fl/fl mice transfected with Fbp2-shRNA retained the structural contour of tendons. In contrast, shRNA controls exhibited irregular and shrunken tendon surfaces at 4 and 8 weeks postoperatively (Fig. 7H). HE and Masson's trichrome staining revealed severe collagen disorganization in the tendons of the control groups. In contrast, tendons from the shRNA-Fbp2 groups exhibited more aligned and thicker collagen fibers. The results suggest that local injection of AAV-Fbp2-shRNA effectively promoted tendon healing and improved healing quality at 4 and 8 weeks after the operation (Fig. 7I and Fig. S11B).

Discussion

While AMPK has been implicated in tissue regeneration [19, 20, 37], the specific role of macrophage-derived AMPKα1 in tendon repair remains largely unexplored. In this study, we observed differential macrophage response between neonatal and adult tendons following injury and utilized transgenic mice to validate the impact of macrophage AMPKα1 activation on tendon regeneration. Additionally, transcriptomic sequencing analysis and in vitro experiments further elucidated the impact of macrophage AMPKα1 knockout on the biological functions of TSPCs and identified a novel regulating mechanism of the TNF-α/AKT/FBP2 axis in TSPCs, providing a new avenue of therapy for tendon repair. These findings provide potential regulatory targets and new insights into the regulation of TSPC function, as well as tendon tissue regeneration and repair.

Fbp2 knockdown in TSPCs notably enhances tendon regeneration. (A) Schematic illustration showing TSPCs transfected with si Fbp2 were loaded onto scaffolds and implanted in the subcutaneous space of nude mice. This figure was created using Figdraw. (B) Representative images for HE (top), Masson (middle), and Sirius red staining (polarized light) of newborn tendon-like tissue at 8 weeks after implantation. Scale bars: 50 µm. (C) Representative TEM images of newborn tendon-like tissue at 8 weeks after implantation. Scale bars: 200 nm. (D) Immunofluorescent staining of TNC and FMOD in newborn tendon-like tissue at 8 weeks after implantation. DIC: differential interference contrast. Scale bars: 20 µm. (E) Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence staining of TNC and FMOD (n = 5). (F) Immunofluorescent staining of the colocalization of SCX (green) and Ki67 (red) in newborn tendon-like tissue at 8 weeks after implantation. Scale bars: 20 µm. (G) Quantitative analysis of immunofluorescence staining of SCX and Ki67 double-positive cells (n = 5). (H) Gross view of tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl and Ampkα1fl/fl mice injected with AAV-Fbp2-shRNA and control AAV-shRNA at 4 and 8 weeks after injury. (I) Representative HE staining and Masson trichrome staining of the tendon from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice and Ampkα1fl/fl mice injected with AAV-Fbp2-shRNA and control AAV-shRNA at 8 weeks after injury. Low magnification image scale bars: 500 μm; high magnification image scale bars: 100 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001.

It is well known that many human tissues and organs, such as the myocardium and spinal cord, exhibit strong regenerative capacity during the neonatal period, which declines markedly with age [4, 38]. Aurora et al. observed different subtypes of macrophages in neonatal mice after myocardial infarction; however, the differences between neonatal and adult macrophages, as well as the mechanisms regulating these differences, remain to be determined [39]. Our data suggest that AMPKα1 participates in regulating the differential changes in the function and phenotype of neonatal and adult macrophages and further elucidate the substantial role of macrophage AMPKα1 in tendon repair. Here, we used LysM-Cre transgenic mice to generate mice deficient in AMPKα1 in BMDMs. However, monocyte-derived macrophages do not necessarily represent all types of macrophages in vivo, and the LysM-Cre system deletes AMPKα1 from all myeloid cells—not only macrophages but also monocytes and granulocytes. In addition, during the process of injury, various components within the tendon tissue, including endothelial cells, TSPCs, other immune cells, and even local macrophages from neighboring tissues, such as calf muscle, participate in the entirety of injury regeneration and repair. While previous studies have shown that macrophage polarization influences tendon regeneration via soluble factors, other signaling pathways including STAT3, NF-κB and WNT, and extracellular vesicles, our findings reveal that AMPKα1 deficiency in macrophages not only promotes a pro-inflammatory phenotype but also disrupts TNF-FBP2 signaling in TSPCs. This non-enzymatic function of FBP2 links inflammatory signaling to mitochondrial metabolism, providing a mechanistic bridge between immune regulation and tendon repair.

Moreover, we identified Fbp2 as a novel candidate gene in TSPCs that responds to macrophage-derived inflammatory signals, such as TNF-α, and mediates TSPC dysfunction. Recently, FBP2 has emerged as a prominent target enzyme in energy metabolism [23, 40, 41]. Beyond its role as a rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis involved in glucose metabolism, FBP2 also has various functions, such as participation in mitochondrial biogenesis, cell cycle regulation, and transcriptional activation of hypoxia-inducible factors, among other biological processes [42, 43]. In our study, we found no obvious changes at the gene level in FBP1, an isozyme of FBP2. We speculate that this could be attributed to the different distributions of the two isozymes: FBP1 is primarily detected in the liver and kidney, whereas FBP2 expression is more ubiquitous in tissues [44]. Additionally, emerging evidence suggests that FBP2 can undergo conformational changes and regulate mitochondrial function via protein-protein interactions independent of its catalytic activity [36]. While our data collectively support a non-enzymatic, regulatory role for FBP2 in mitochondrial homeostasis, we acknowledge that the precise molecular mechanism, particularly its potential non-enzymatic interactions, has not been fully elucidated. Moreover, future studies using stable genetic models or conditional Fbp2 knockout strategies will be necessary to fully evaluate the long-term and inflammation-resistant effects of FBP2 depletion in TSPCs.

Mitochondria regulate a variety of cellular processes that are closely associated with tissue injury and repair, such as cell death, proliferation and differentiation, metabolic adaptation, and inflammation [45, 46]. After tissue injury, excessive mitochondrial fission mediated by DRP1 mitochondrial translocation can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction [47], resulting in reduced ATP synthesis, massive ROS accumulation, reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, and ultimately leading to TSPC dysfunction [48, 49]. Here, we demonstrated that TSPCs isolated from LysM-Cre; Ampkα1fl/fl mice displayed high expression of ROS and mitochondrial dysfunction, mainly caused by macrophage AMPKα1 depletion-induced immune imbalance. Notably, suppression of DRP1 hyperactivation attenuated these abnormal events in Fbp2 knockdown experiments. Mitochondrial biogenesis is a genetically regulated program for mitochondrial proliferation during cell division and cellular stress, and stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis has been demonstrated to facilitate tissue recovery after injury [50, 51]. We also reported that Fbp2 knockdown successfully restored the mitochondrial biogenic function by increasing the expression of PGC-1α and NRF1 proteins. PGC-1α is the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis that regulates metabolic rewiring in the face of different environmental cues and metabolic demand [52]. Among these, PGC-1α-regulated targets related to mitochondrial biogenesis include the NRF1 and NRF2 and mitochondrial transcription factor A [46]. Hence, activation of PGC-1α can promote the expression of mitochondrial biogenesis, increase mitochondrial mass, and reduce mitochondrial ROS levels. Moreover, one limitation of the present study is the lack of functional assessments. Beyond structural evaluation, functional indices including mechanical testing and gait analysis will be considered in future work to further validate tendon healing outcomes.

Overall, this study demonstrates that specific knockout of macrophage Ampkα1 restricts the transition of the macrophage anti-inflammatory phenotype during tendon regeneration. Furthermore, it affects the mitochondrial function of TSPCs by regulating the key glycolytic enzyme, FBP2, thereby reducing cell stemness and tendon differentiation potential. In summary, the research elucidates the mechanism by which macrophage AMPKα1 influences tendon regeneration, identifying and deciphering novel targets for regulating stem cell and tendon regeneration capacity.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods, figures and tables.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China 2024YFA1210400 (Y.L.), Beijing Natural Science Foundation L234017 (Y.L.), National Natural Science Foundations of China 82230030 (Y.L.) and 82571058 (Y.W.), Beijing Nova Program 20240484655 (Y.L.), Z211100002121043 (Y.W.) and 20250484970 (Y.W.), Peking University Medicine plus X Pilot Program-Key Technologies R&D Project 2024YXXLHGG004 (Y.L.), First-Class Discipline Team of Kunming Medical University 2024XKTDTS08 (Y.L.), Peking University Clinical Scientist Training Program, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities BMU202SPYJH019 (Y.W.), Peking University Clinical Medicine Plus X - Young Scholars Project, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities PKULCXQ02 (Y.W.), China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents BX2021022 (Y.W.), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation 2021M700281 (Y.W.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: LY, JN. Methodology: LY, ZLS, WY. Data analysis: ZLS, WY, WTH, SXM. Investigation: ZLS, WY, YM, CXJ, CLY. Visualization: ZLS, WY, ZH, WXL, DCY. Supervision: LY, JN, ZLS, WY, LHB, ZSY, LC. Writing—original draft: ZLS, WY. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Compliance with ethics requirements

All the experimental procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with animal welfare ethical regulations and approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of Peking University (LA2020349).

Data availability

The data sets used for the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The whole transcriptome microarray data were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database with the accession number GSE314597.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Nourissat G, Berenbaum F, Duprez D. Tendon injury: from biology to tendon repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:223-33

2. Rees JD, Stride M, Scott A. Tendons-time to revisit inflammation. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1553-7

3. Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity. 2016;44:450-62

4. Simões FC, Cahill TJ, Kenyon A, Gavriouchkina D, Vieira JM, Sun X. et al. Macrophages directly contribute collagen to scar formation during zebrafish heart regeneration and mouse heart repair. Nat Commun. 2020;11:600

5. Mosser DM, Hamidzadeh K, Goncalves R. Macrophages and the maintenance of homeostasis. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2021;18:579-87

6. Wang J, Zhao Q, Fu L, Zheng S, Wang C, Han L. et al. CD301b(+) macrophages mediate angiogenesis of calcium phosphate bioceramics by CaN/NFATc1/VEGF axis. Bioact Mater. 2022;15:446-55

7. Sheng R, Liu J, Zhang W, Luo Y, Chen Z, Chi J. et al. Material Stiffness in Cooperation with Macrophage Paracrine Signals Determines the Tenogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10:e2206814

8. Schoenenberger AD, Tempfer H, Lehner C, Egloff J, Mauracher M, Bird A. et al. Macromechanics and polycaprolactone fiber organization drive macrophage polarization and regulate inflammatory activation of tendon in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials. 2020;249:120034

9. Zhu L, Wang Y, Jin S, Niu Y, Yu M, Li Z. et al. Parishin A-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles modulate macrophage polarization to attenuate tendinopathy. NPJ Regen Med. 2023;8:14

10. Zou NY, Liu R, Huang M, Jiao YR, Wei J, Jiang Y. et al. Age-related secretion of grancalcin by macrophages induces skeletal stem/progenitor cell senescence during fracture healing. Bone Res. 2024;12:6

11. Ratnayake D, Nguyen PD, Rossello FJ, Wimmer VC, Tan JL, Galvis LA. et al. Macrophages provide a transient muscle stem cell niche via NAMPT secretion. Nature. 2021;591:281-7

12. Wang X, Chen H, Tian R, Zhang Y, Drutskaya MS, Wang C. et al. Macrophages induce AKT/β-catenin-dependent Lgr5(+) stem cell activation and hair follicle regeneration through TNF. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14091

13. Lee CH, Lee FY, Tarafder S, Kao K, Jun Y, Yang G. et al. Harnessing endogenous stem/progenitor cells for tendon regeneration. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2015;125:2690-701

14. Brunet A, Goodell MA, Rando TA. Ageing and rejuvenation of tissue stem cells and their niches. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2023;24:45-62

15. Wang Y, Jin S, Luo D, He D, Shi C, Zhu L. et al. Functional regeneration and repair of tendons using biomimetic scaffolds loaded with recombinant periostin. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1293

16. Li Y, Li H, Pei J, Hu S, Nie Y. Transplantation of murine neonatal cardiac macrophage improves adult cardiac repair. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:492-4

17. Winterberg T, Vieten G, Meier T, Yu Y, Busse M, Hennig C. et al. Distinct phenotypic features of neonatal murine macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:214-24

18. Lavine KJ, Epelman S, Uchida K, Weber KJ, Nichols CG, Schilling JD. et al. Distinct macrophage lineages contribute to disparate patterns of cardiac recovery and remodeling in the neonatal and adult heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16029-34

19. Ono H, Suzuki N, Kanno SI, Kawahara G, Izumi R, Takahashi T. et al. AMPK Complex Activation Promotes Sarcolemmal Repair in Dysferlinopathy. Mol Ther. 2020;28:1133-53

20. McArthur S, Juban G, Gobbetti T, Desgeorges T, Theret M, Gondin J. et al. Annexin A1 drives macrophage skewing to accelerate muscle regeneration through AMPK activation. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2020;130:1156-67

21. Baardman J, Verberk SGS, Van Der Velden S, Gijbels MJJ, Van Roomen CPPA, Sluimer JC. et al. Macrophage ATP citrate lyase deficiency stabilizes atherosclerotic plaques. Nature Communications. 2020;11:6296

22. Xiao J, Wang S, Chen L, Ding X, Dang Y, Han M. et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol regulates lysosome AMP kinase activation and metabolic reprogramming to educate immunosuppressive macrophages. Immunity. 2024;57:1087-104.e7

23. Huangyang P, Li F, Lee P, Nissim I, Weljie AM, Mancuso A. et al. Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase 2 Inhibits Sarcoma Progression by Restraining Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Cell Metabolism. 2020;31(1):174-188.e7

24. Li H, Wang J, Xu H, Xing R, Pan Y, Li W. et al. Decreased fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase-2 expression promotes glycolysis and growth in gastric cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:110

25. Zhu L, Wang Y, Jin S, Niu Y, Yu M, Li Z. et al. Parishin A-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles modulate macrophage polarization to attenuate tendinopathy. NPJ Regenerative Medicine. 2023;8:14

26. Wang Y, Jin S, Luo D, He D, Shi C, Zhu L. et al. Functional regeneration and repair of tendons using biomimetic scaffolds loaded with recombinant periostin. Nature Communications. 2021;12:1293

27. Kaneda MM, Messer KS, Ralainirina N, Li H, Leem CJ, Gorjestani S. et al. PI3Kγ is a molecular switch that controls immune suppression. Nature. 2016;539:437-42

28. Wang Y, Jin S, Luo D, He D, Yu M, Zhu L. et al. Prim-O-glucosylcimifugin ameliorates aging-impaired endogenous tendon regeneration by rejuvenating senescent tendon stem/progenitor cells. Bone Research. 2023;11:54

29. Cui Y, Chen J, Zhang Z, Shi H, Sun W, Yi Q. The role of AMPK in macrophage metabolism, function and polarisation. J Transl Med. 2023;21:892

30. Wang Y, Wang J, Zhang J, Wang Y, Wang Y, Kang H. et al. Stiffness sensing via Piezo1 enhances macrophage efferocytosis and promotes the resolution of liver fibrosis. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadj3289

31. Zhang X, Xiao Y, Hu B, Li Y, Zhang S, Tian J. et al. Multi-omics analysis of human tendon adhesion reveals that ACKR1-regulated macrophage migration is involved in regeneration. Bone Res. 2024;12:27

32. Best KT, Korcari A, Mora KE, Nichols AE, Muscat SN, Knapp E. et al. Scleraxis-lineage cell depletion improves tendon healing and disrupts adult tendon homeostasis. Elife. 2021;10:e62203

33. Fu W, Yang R, Li J. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal changes in cell heterogeneity during progression of human tendinopathy. BMC Biol. 2023;21:132

34. Bishop EL, Gudgeon N, Fulton-Ward T, Stavrou V, Roberts J, Boufersaoui A. et al. TNF-α signals through ITK-Akt-mTOR to drive CD4(+) T cell metabolic reprogramming, which is dysregulated in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Signal. 2024;17:eadg5678

35. García-Prat L, Perdiguero E, Alonso-Martín S, Dell'Orso S, Ravichandran S, Brooks SR. et al. FoxO maintains a genuine muscle stem-cell quiescent state until geriatric age. Nature Cell Biology. 2020;22:1307-18

36. Duda P, Budziak B, Rakus D. Cobalt Regulates Activation of Camk2α in Neurons by Influencing Fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase 2 Quaternary Structure and Subcellular Localization. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4800

37. Watanabe S, Alexander M, Misharin AV, Budinger GRS. The role of macrophages in the resolution of inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:2619-28

38. Li Y, He X, Kawaguchi R, Zhang Y, Wang Q, Monavarfeshani A. et al. Microglia-organized scar-free spinal cord repair in neonatal mice. Nature. 2020;587:613-8

39. Aurora AB, Porrello ER, Tan W, Mahmoud AI, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R. et al. Macrophages are required for neonatal heart regeneration. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:1382-92

40. Osipova E, Barsacchi R, Brown T, Sadanandan K, Gaede AH, Monte A. et al. Loss of a gluconeogenic muscle enzyme contributed to adaptive metabolic traits in hummingbirds. Science. 2023;379:185-90

41. Pietras Ł, Stefanik E, Rakus D, Gizak A. FBP2-A New Player in Regulation of Motility of Mitochondria and Stability of Microtubules in Cardiomyocytes. Cells. 2022 11(10), 1710

42. Park HJ, Jang HR, Park SY, Kim YB, Lee HY, Choi CS. The essential role of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase 2 enzyme in thermal homeostasis upon cold stress. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:485-96

43. Pirog M, Gizak A, Rakus D. Changes in quaternary structure of muscle fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase regulate affinity of the enzyme to mitochondria. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;48:55-9

44. Malz M, Weber A, Singer S, Riehmer V, Bissinger M, Riener MO. et al. Overexpression of far upstream element binding proteins: a mechanism regulating proliferation and migration in liver cancer cells. Hepatology. 2009;50:1130-9

45. Harrington JS, Ryter SW, Plataki M, Price DR, Choi AMK. Mitochondria in health, disease, and aging. Physiological Reviews. 2023;103:2349-422

46. Tang C, Cai J, Yin X-M, Weinberg JM, Venkatachalam MA, Dong Z. Mitochondrial quality control in kidney injury and repair. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2021;17:299-318

47. Choi GE, Lee HJ, Chae CW, Cho JH, Jung YH, Kim JS. et al. BNIP3L/NIX-mediated mitophagy protects against glucocorticoid-induced synapse defects. Nat Commun. 2021;12:487

48. Zhang X, Wang R, Hu D, Sun X, Fujioka H, Lundberg K. et al. Oligodendroglial glycolytic stress triggers inflammasome activation and neuropathology in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Adv. 2020 6(49), eabb8680

49. Zeng X, Zhang YD, Ma RY, Chen YJ, Xiang XM, Hou DY. et al. Activated Drp1 regulates p62-mediated autophagic flux and aggravates inflammation in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via the ROS-RIP1/RIP3-exosome axis. Mil Med Res. 2022;9:25

50. Cheng X-T, Huang N, Sheng Z-H. Programming axonal mitochondrial maintenance and bioenergetics in neurodegeneration and regeneration. Neuron. 2022;110:1899-923

51. Hwang J-H, Kim KM, Oh HT, Yoo GD, Jeong MG, Lee H. et al. TAZ links exercise to mitochondrial biogenesis via mitochondrial transcription factor A. Nature Communications. 2022 13(1), 653

52. Ng MYW, Wai T, Simonsen A. Quality control of the mitochondrion. Developmental Cell. 2021;56:881-905

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: E-mail: nanjiangedu.cn (N.J.); orthoyanedu.cn (Y.L.). Phone: +861082195975 (Y.L.).

Corresponding authors: E-mail: nanjiangedu.cn (N.J.); orthoyanedu.cn (Y.L.). Phone: +861082195975 (Y.L.).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact